Shapur II (r. 309-379 CE, also Sapur II) was the tenth monarch of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) and among the most successful. Under his reign – which lasted his entire life – the Avesta (Zoroastrian scripture) was committed to writing and the empire expanded at the expense of the Arab tribes, the Roman Empire, and the kingdoms of the East.

Shapur II is said to have been literally crowned in the womb, an exaggeration of the fact that he was made king shortly after his birth. The Persian government was administered by his advisors until his 16th birthday when he came of age and took personal control of his kingdom.

He first drove the Arabs from the Persian Empire and expanded his territory to the south, then reclaimed lands to the north and west from Rome while also expanding his reach to the East. By the time of his death, he had improved so many aspects of life in the Sassanian Empire that his reign marks its first Golden Age.

In Roman history, he is noted as the Persian king who killed the emperor Julian (r. 361-363 CE) at Samarra, delivered the humiliating peace treaty to the emperor Jovian (r. 363-364 CE) afterwards and for his persecution of the Christians in his territories. In Persian history, these events are also recognized but he is remembered as the greatest king after Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) and before Kosrau I (r. 531-579 CE). His reign, in fact, set the standard by which his successors would measure their own and was unsurpassed until Kosrau I came to power.

Background & Rise to Power

Following the spectacular reign of Shapur I, the Sassanians were led by a series of fairly ineffectual monarchs who struggled – and failed – to measure up his successes or those of his father (and founder of the empire), Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE). Shapur I's son, Hormizd I (r. 270-271 CE) succeeded him but ruled only a year before he was replaced by his brother Bahram I (r. 271-274 CE) who was almost completely controlled by the magi (priestly class) and, under their influence, reversed the policy of religious tolerance by killing the prophet Mani (l. 216-274 CE), and persecuting his followers. He also made an enemy of the Romans by promising help to the Queen Zenobia (l. c. 240 CE) of Palmyra in her struggles against them; a promise he never even honored but which Rome would not forget.

He was succeeded by his son, Bahram II (r. 274-293 CE) who continued to be controlled by the magi, failed to repel the Romans under the emperor Carus (r. 282-283 CE), and lost Armenia to them. His son, Bahram III (r. 293 CE) was so ineffective he was removed by his great uncle Narseh (also given as Narses, r. 293-302 CE) after less than a year. Narseh finally stabilized the empire but was defeated in battle by the Romans and forced by Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE) to sign the Treaty of Nisibis in 297 CE, ceding significant territory to Rome so that the border between the two empires was now the Tigris, right at the foot of the Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon.

Narseh was succeeded by his son Hormizd II (r. 302-309 CE) who focused on administration and made no military advances to try to regain what had been lost. When he died, after an uneventful reign, his son Adur Narseh may have briefly ruled, but this claim is challenged. Whether he actually held power or not, Adur Narseh was seen as a threat by the nobles who had him killed, blinded his brother, and imprisoned another brother, Hormizd (who would later escape to Rome and fight against the Sassanians). The advisors of Hormizd II, tired of having to endure a succession of ineffectual monarchs and thinking they could control one they molded, crowned Hormizd II's newborn son Shapur II in 309 CE and then acted as regents until he came of age.

These advisors, however, were no more effective than the previous monarchs had been and did nothing when Arab tribes began invading Sassanian regions from the south, establishing themselves in communities from Pars to Mazun from which they would launch raids. The young king's advisors also did nothing to curb the increasing power of the magi in politics (as many of them were probably of that class) nor did they initiate any policies to regain any of the lands lost to Rome. Nothing is known of Shapur II's upbringing but, after his coronation at Ctesiphon at the age of 16, he took immediate action to reverse the empire's fortunes beginning with the expulsion of the Arabs.

Arab Campaigns

Ardashir I had modeled his new empire on that of the earlier Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), including the elite infantry force of the Persian Immortals, who were reformed by Ardashir I as cavalry known as the Savaran Knights. Between the time of Hormizd I and Hormizd II, the knights – as well as almost every other aspect of Persian warfare and government – had been allowed to degenerate. Scholar Kaveh Farrokh notes:

The Arab successes were mainly due to the absence of any meaningful Sassanian military response. The boy-emperor Shapur II was surrounded by a large number of indecisive and mediocre advisors who proved incompetent at stopping the Arabs. The Sassanian military machine was certainly capable of at least containing the Arab raids. It is a mystery as to why the advisors to the boy-king failed to mobilize the armed forces to confront the threats. (198)

Shapur II reformed the military and then personally led the campaign against the Arabs. The heavily armed and armored Savaran Knights destroyed the more lightly armed Arab cavalry while Sassanian infantry and archers neutralized Arab foot-soldiers. Pars and Mazun were quickly liberated and the Persian Gulf coastline reclaimed. Afterwards, Shapur II loaded his army onto ships and sailed across the Gulf to confront the Arabs on their own ground, taking Bahrain, Ghateef, and Yamama, and defeating the Arab forces in every engagement before returning home.

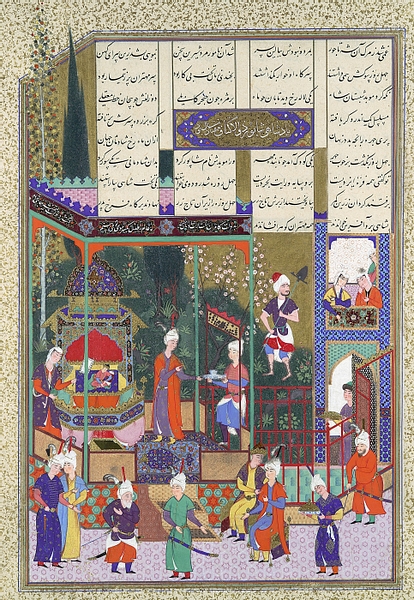

His exploits in Arabia would later become legendary, depicting excessive cruelty and ruthlessness such as removing prisoners' shoulder blades and leading them by ropes strung through their wounds across arid desert plains. These campaigns also inform the episode of the epic Shahnameh, the Persian Book of Kings, involving the Arabian princess Malika and her father Ta'ir, both of whom Shapur II has executed.

After returning home, he ordered defensive walls built along the southern borders of the empire, modeled on Roman walls and fortifications in Syria. In doing so, Shapur II was continuing the policies of Ardashir I and Shapur I in taking aspects from other cultures – or their own earlier history – and improving upon them. This policy of taking the best aspects of the past (or from others) and adapting them for their own purposes would come to define the Sassanian Empire, at least among its most effective kings, for the rest of its history.

Conflict with Rome

Shapur II also modeled himself on Ardashir I by demanding from the Romans all the regions formerly owned by his ancestors. Ardashir I had done this same thing in requiring Rome to surrender the territory once held by the Achaemenids and now Shapur II claimed those lands lost by Narseh to Diocletian. The Romans responded by increasing their support of the Christian king of Armenia against any Sassanian incursions.

Constantine the Great had worsened Rome's relations with the Sassanians in 312 CE by recognizing Christianity as a legitimate religion of his empire and declaring himself a protector and defender of all Christians, including those living in Sassanian territories. Now, according to the Sassanian interpretation, Rome was actively encouraging Christianity in neighboring Armenia – a region they believed rightly belonged to them.

Shapur II and his advisors recognized this as a serious threat in that Rome could now use religion to sow dissent in the empire by pitting Christians against Zoroastrians and Armenians against Sassanian Persians. Shapur II decided to move first and, in 337 CE, invaded Roman Mesopotamia and took Armenia. He then reversed the traditional Persian policy of religious tolerance and inclusion and declared a double tax on all Christians in the empire. When the Christian leader Shemon bar Sabbae refused to pay the tax and told others not to, the Sassanian persecution of Christians was initiated which, according to later historians (such as Sozomen, l. c. 400 - c. 450 CE), resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 Christians.

Roman Campaigns & Wars in the East

The first war with Rome (337-350 CE) centered around the Roman city-fortress of Nisibis (modern-day Nusaybin, Turkey). Shapur II needed to take Nisibis in his advance against Rome because he could not leave a Roman fortified position behind his lines. He attempted to take the city in 338, 346, and 350 CE, but the defenders held it each time. While he was making his third attempt, his empire was attacked in the east by the Chionites (synonymous with the nomadic Xiongnu raiders, according to some sources) and had to break off war with Rome to secure his borders. He enlisted the aid of his younger brother Ardashir (later his successor, Ardashir II, r. 379-383 CE) in these wars, but it is unclear what position Ardashir held or what his contributions were.

He struggled to expel the Chionites for seven years, during which time he expanded his empire eastwards, stabilizing the Kushano-Sassanian kingdoms (territories taken by the Sassanians of Bactria from the Kushans) and bringing them into the empire. By c. 357 CE, the Chionite threat had been neutralized and Shapur II returned to his war with Rome the following year.

In 359 CE, he besieged the city of Amida which held against repeated assaults for 73 days before it fell. He marched on to take other Roman centers, such as Singara, but in this engagement, as at Amida, he suffered significant casualties. Shapur II garrisoned the sites he had taken and retired to regroup and resupply over the winter. Before he could launch another campaign, however, the Roman army moved against him.

In 363 CE, the Roman emperor Julian marched on Shapur II with a force estimated at between 65,000-95,000. He divided the army between his command – which proceeded directly toward Ctesiphon – and a smaller force under his cousin Procopius (l. c. 326-366 CE) which moved north and was then going to meet Julian's army above Ctesiphon to crush the Sassanians between them.

This strategy ignored the lesson which should have been learned at the first Battle of Ctesiphon in 233 CE when Alexander Severus (r. 222-235 CE), who had also divided his army in similar fashion, was defeated by Ardashir I. If Severus had advanced on Ctesiphon with his full force, he would probably have been victorious, and the same holds for Julian's campaign.

Julian made a number of even more impressive mistakes, however, such as burning his boats (either to prevent his troops from retreating or to keep the ships from falling into Sassanian hands) and advanced on Ctesiphon with meager supplies, believing he would take the city quickly, end the war, and return home. He only had half of his troops, however, and Ctesiphon was so heavily defended that the Roman forces could not take it. Procopius' army failed to arrive and, while Julian waited for him, his casualties increased while his supplies dwindled.

Julian had to call off the attack but, with no way to retreat back across the river, was forced to march north to try to get back to Roman territory. At the Battle of Samarra in 363 CE, he was mortally wounded by a spear thrown by the enemy and died shortly afterwards.

Julian was succeeded by Jovian who, surrounded by enemy forces and with no means of escape, was forced to accept Shapur II's conditions in a humiliating treaty which returned all the lands Shapur II had asked for initially and drove Rome out of Mesopotamia.

Religious Policies & Administration

After ordering the evacuation of Roman citizens from the cities he had taken, Shapur II repopulated them with Persians. He restored and repopulated Nisibis and Susa, among others, and built a new city – Eranshahr-Shapur – which became home to the Roman prisoners of war who had worked on it. In addition to his building projects, he continued to stabilize his government by reforming it so that the magi no longer held their previous power over the throne and the ambitions of the nobility were restricted by clear rules of succession.

Although he has been criticized for his persecution of the Christians, he had nothing against the religion itself and, initially, allowed Christians to worship and even proselytize as freely as any other in his realm. He only shifted this policy when he came to regard Christianity as a distinctly Roman religion which could be weaponized against the stability of the empire. He was not the only king to have come to this conclusion. Athanaric, king of the Goths (d. 381 CE) pursued the same policy for the same reasons as early as 348 CE and almost continuously between 369-372 CE. Athanaric believed – with good reason – that Christian missionaries were undermining his people's traditional beliefs and weakening his authority as king. Shapur II's persecutions were launched in an effort to prevent this same threat from gaining ground in his empire.

No other religious groups suffered persecution under his reign, and, in fact, he encouraged the worship of Anahita as a deity, which strict Zoroastrianism discouraged. This may have been part of his policy of decreasing the power of the magi at court by undercutting their authority but, whatever his reasons, he maintained his predecessors' policies of advancing Zoroastrianism as the state religion while allowing any other faith free expression. Like many of the Sassanian kings, Shapur II was probably not a strict Zoroastrian himself but, rather, an adherent of Zorvanism, a belief system based on Zoroastrianism but deviating in significant aspects.

In Zoroastrianism, there was one supreme god – Ahura Mazda – who was in continuous conflict with his opponent, the evil Angra Mainyu (also known as Ahriman), and the purpose of human life was to join forces with Ahura Mazda and fight against the forces of darkness. Zorvanism replaced Ahura Mazda with the god Zorvan (representing Infinite Time) and made Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu twin brothers born of this god. The meaning of one's life remained the same – to stand for good against darkness and evil – but Ahura Mazda was now a created being like any other, born of Time and subject to Time's strictures.

Evidence for Shapur II's Zorvanist leanings comes from inscriptions and Roman writers which relate how he identified himself with the gods as their brother – as a fellow created being – and claimed lineage from them. Achaemenid Zoroastrian rulers claimed their authority to rule from Ahura Mazda but did not make these same kinds of claims of blood relations with their deities.

In the area of religion, his greatest contribution was completing the work of Ardashir I and Shapur I in committing the Avesta to writing and expanding on the oral tradition of Zoroastrianism through written works. Shapur II's efforts in this regard would be continued and further expanded under Kosrau I and are the only reason the tenets of Zoroastrianism are known in the present day. These writings were copied and studied at intellectual and cultural centers such as Gundeshapur (also the world's first teaching hospital) and at the other institutes of higher learning Shapur II encouraged and patronized.

Conclusion

Shapur II died of natural causes in 379 CE after naming Ardashir II his successor. Ardashir II only ruled on the condition that he would relinquish rule to Shapur II's son, Shapur III (r. 383-388 CE) when the boy came of age. Neither of Shapur II's immediate successors would distinguish themselves or live up in any way to the standard he had set for them. Farrokh writes:

Shapur II was perhaps one of the most enigmatic rulers of ancient Persia. Ruling literally from the cradle to the grave, Shapur's 70-year reign spanned the passage of ten Roman emperors and witnessed desperate battles with the Arabs, Chionites, and Romans…Shapur steered Persia through these crises, and also laid the foundations of a powerful learning tradition. That legacy was to profoundly influence the later Islamic, and European, traditions of learning and medicine. (198)

Shapur II's contributions to these later traditions are never disputed, but an aspect of his reign often overlooked is the consequence of his legendary ruthlessness in his campaigns in Arabia. Even if there is no truth to the legends, they came to inform Arabian animosity toward the Persians.

The Sassanian Empire finally fell to the Arabs in the 7th century CE and, between c. 632-651 CE, the Muslim Arabs paid the Sassanians back in full for the stories they had heard of the brutal campaigns of Shapur II in their lands. Whether the alleged brutalities ever occurred will probably never be known, however, and Shapur II is better remembered as a great king whose reign allowed for the development of the arts, sciences, religion, and the flourishing of one of antiquity's most noble civilizations.