The Social War (also called the Marsi War or the War of the Allies) of 91-87 BCE was the result of decades of contention between Rome and its Italian allies. Roman warfare relied heavily on the Italian allies (socii), but the Roman Republic did not grant them citizenship. The main cause of the Social War was this inequality in status.

Causes

This tension had its beginnings at the very onset of the Roman expansion across the Italian peninsula. Between 500 and 275 BCE, the citizen armies of the Roman Republic brought Latium and the remainder of the peninsula under its thumb. While allowing these newly acquired allies limited self-government, Rome demanded one thing from them: loyalty. This loyalty brought with it a distinct benefit for Rome: an unlimited supply of manpower for its military campaigns. As Rome reached across the Mediterranean with its long arms into Spain, Greece, North Africa, and Asia, its demand for manpower increased. As Rome demanded more and more from its Italian allies, the tension grew with it.

On the field of battle, the famed Roman army depended heavily on their allies or alae (Latin for wings) to supplement their ranks. Often, the alae provided as many infantry soldiers as did the legions and three times the cavalry. In battle, the legions took the center, while the alae were stationed on their flanks. The alae were commanded by three prefects (praefecti sociorum) who were usually Roman citizens. The best of the alae formed the extraordinarii, a force of both cavalry and infantry used at the discretion of the consul. However, the Roman legionary and his allied counterpart were not equals, for the Roman was a citizen and the ala was not. Over time, this difference would intensify and prove to be one of the major causes of the Social War. Another major difference separating the two was that the ala paid taxes while the Roman citizen did not. Without citizenship, and therefore no voice in the Roman government, an ala had no say in how his tax money was spent.

The Italian Question

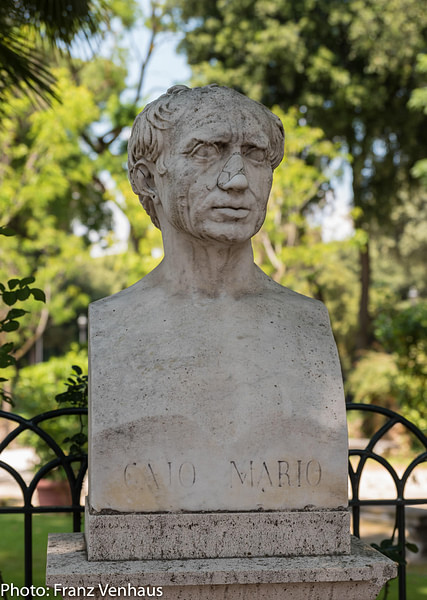

This repeated denial of citizenship had eaten at the allies for decades. Promises had been made, and promises had been broken. To the allies, it was a game the Roman Senate played. Historian M. Beard wrote that while the allies "reaped handsome rewards" in the form of booty from Roman victories, the "'Italian question' became increasingly divisive and provoked bouts of violent conflict" (236). However, not all Italians were denied voting rights. Upon being annexed in 338 BCE, Latium had received Latin Rights or ius Latii, allowing them to operate on a semi-equal footing with the Romans – they could marry Romans, enter into contracts, and engage in land claims. They also had the right to vote in the Assembly. The allies – foederati or socii – were not annexed to Rome and thereby had no civil or political rights, yet they still had to provide manpower. By 100 BCE, they supplied two-thirds of the Roman army. The great military reformer Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 BCE) had always been a proponent of the Italian cry for rights, having fought alongside them in battle. As consul, he often rewarded exemplary service with citizenship. Unfortunately, this only further fueled discontent.

Attempts at Reform

The push for allied citizenship began at least three decades before the onset of the war. Along with Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, the brothers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus stood as strong advocates for allied rights. In 125 BCE, Flaccus was a consul and proposed legislation for full Italian citizenship to the Assembly. Unfortunately, about the same time, marauders, the Salluvii, were running rampant in Gaul. The Senate sent Flaccus north to quell the disturbance. Upon his return and with his consulship complete, the bill died. Another sign of the allies' continued discontent with Rome came after the failure of Flaccus' bill when the city of Fregellae revolted. The city had been loyal to Rome against Pyrrhus in the Pyrrhic War (280-275 BCE) and Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE). Praetor Lucius Optimus was sent to investigate; the city was brutally sacked and its walls destroyed. Some believe its sacking was intended as a message to other cities.

In 122 BCE, tribune Gaius Gracchus proposed a measure to the Assembly concerning voting and citizenship rights for the allies. Although not as broad as Flaccus' proposition, he proposed that those who presently had Latin Rights would be elevated to full Roman citizenship while the allies would be granted Latin Rights. However, for this to succeed, the allies needed to drop their demands for land distribution. They refused. Gaius' failure was due, in part, to the consul Lucius Optimus who made it his goal to destroy Gaius. He was successful. Gaius and Flaccus would meet the same fate as did Gaius' brother: death. Flaccus was executed on a side street on the Aventine Hill, while Gaius chose to die by his own hand, ordering his slave to stab him in the neck. At least 250 people died that day with thousands more executed within the days that followed. Optimus had eliminated all of Gaius' supporters in Rome – even Flaccus' son, who, at least, chose his own manner of death.

In 95 BCE, Lucius Licinius Crassus (140-91 BCE) became consul and proposed the formation of a commission to clean up the citizenship roles. For years, Rome had seen an influx of allies moving into the city and illegally enrolling as citizens. Crassus and his fellow consul Quintus Mucius Scaevola proposed a bill to expel all those illegal Italians from the city, thereby only Romans could vote.

The torch for Italian citizenship was passed to the wealthy and ambitious nobleman Marcus Livius Drusus (the Younger, c. 124-91 BCE). Drusus became tribune in 91 BCE, having been both praetor and aedile, and like Gaius Gracchus, he had believed in land distribution for the poor. He proposed both the foundation of colonies to reduce population pressure and full citizenship for Latin and Italian allies. Again, as with Gaius Gracchus, the Roman Senate found that granting citizenship to the allies would make them too powerful. And, like his predecessor, Drusus was murdered. In his book Cicero, Antony Everitt describes the final hour of Drusus' life. While conducting a meeting at his home, "… he suddenly screamed that he had been stabbed and fell with the words on his lips." (36) The assassin was never captured. His bills were nullified by the consul Lucius Marcius Philippus.

The mood outside Rome became tense and feverish following the death of Drusus. An old friend of Drusus, Quintus Poppaedius Silo of the Marsi tribe, had spoken with Drusus, explaining that the Italians welcomed the land reform but also sought full citizenship. With Drusus dead, many allies believed it was time for action. When the war finally began, Rome was in for a shock; they had not considered that they were about to face an enemy that had been trained and equipped by Rome.

The War Begins

In 91 BCE, a report reached Rome that the city of Asculum had seized Roman citizens as hostages. A praetor was sent to investigate – he was murdered; other Romans soon met their death. Tom Holland in his Rubicon described the turmoil within the city:

When the rebels captured Asculum, the first city to fall to them, they slaughtered every Roman they could find. The wives of those who refused to join them had then been tortured and scalped. (51)

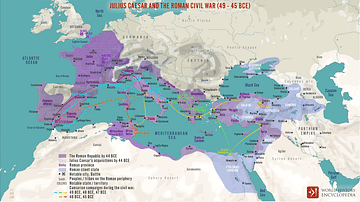

Duncan wrote that the speed "with which the revolt spread is a testament to how long the Italians had been planning" (172). He added that it was a massive coordinated insurrection of at least a dozen tribes. Not everyone, however, was against Rome: the Latins as well as the Umbrians, Etruscans, and the Greek colonies in the south remained loyal to Rome. The major tribes who led the assault were the Samnites and the Marsi – the latter led by Silo. The ally representatives met in the city of Corfinium, renaming it Italia and making it their capital. The new government had a Senate, magistrates and even coinage. Together they had an army of 100,000. Their council presented their demands to Rome: civitas (citizenship) or libertas (independence).

Fighting continued throughout the peninsula. The rebels gained control of Campania, Apulia and Lucania. The Roman Senate panicked, trying to organize a response. Leadership attempted – before actually acting against the rebels – to find someone to blame for the insurrection. Quintus Varius Severus Hybrida proposed a commission to purge all who had supported Italian citizenship, believing they had incited the allies with false promises. The bill passed and exiles soon followed. As the rebels continued their assault against Rome, the government realized it was time for a counter-offensive. Consul Lucius Julius Caesar was assigned to fight the Samnites in the south while Publius Rutilius Lupus was sent north to meet the Marsi. Lastly, Sextus Caesar was sent to Asculum. Among those who fought against the allies was Lucius Cornelius Sulla. He would soon supplant Marius as the premier Roman general.

The Senate finally made an attempt to satisfy the rebels. The Lex Julia, proposed by Lucius Julius Caesar (c. 134-87 BCE), offered full citizenship to any Italian who had not taken up arms against Rome. Meanwhile, some communities in Cisalpine Gaul were given citizenship by Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (consul in 89 BCE) while Gauls on the north side of the Po River received Latin Rights. Another bill, Lex Plautia Papiria, granted citizenship to Italian communities remaining under arms. These two laws kept the rebellion from spreading.

Conclusion

By the end of 89 BCE, the Social War was winding down; the population had been devastated with over 100,000 dead, the economy had suffered, productivity was crippled with grain shortages, and estates had been seized. The war to the north was brought to an end by both diplomacy and fighting. However, as the war seemed out of reach, Italians differed greatly in their outlook; some were determined to fight, while others worked to make a deal. Among those who wished to continue to fight was Silo who led over 10,000 troops. Silo met the Romans as Apulia. He, along with 1100 of his followers, died. This marked the end of the war.

Anthony Everitt in his Cicero wrote that the war signaled a new, bloodier spiral into social and political chaos. After the fighting ended, the number of Roman citizens increased threefold. The question of getting the new citizens into the existing tribes arose, but no system for voter registration ever came to fruition. Only those with money could travel to Rome to vote. However, after the war’s end, the ala-soldier was finally able to join the legions.