Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was an Austrian composer who wrote a wide range of works including piano concertos, string quartets, symphonies, operas, and sacred music. Regarded as one of or perhaps the greatest natural musical talent ever, Mozart died penniless, aged 35, and was buried in an unmarked grave, but his sophisticated, expressive, and joyful work continues to enchant today.

The Child Prodigy

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus) was born in Salzburg, Austria, on 27 January 1756. His father was Leopold Mozart (1719-1787), a violinist and composer, and his mother was Anna Maria Pertl, who added to the family income by making lace. Wolfgang was the youngest of the couple's seven children. Leopold played in the orchestra of the Archbishop of Salzburg from 1743 and had written a popular treatise on violin playing; he earned enough from his own playing to live on the Getreidegasse (no. 9) in Salzburg.

Wolfgang was a child prodigy, and he studied both keyboard and composition from age five. Wolfgang's one sibling that survived infancy was his elder sister Maria Anna (nicknamed 'Nannerl', 1751-1829), who was also a talented pianist. Maria Anna, being a woman and victim of the social restrictions of the period, was obliged to give up any idea of public performance. Wolfgang, meanwhile, continued to mesmerise with his natural talent wowing audiences not only with his playing but with such 'tricks' as improvisation, sight-reading any given piece faultlessly, playing with the keyboard covered with a cloth, and writing down note-perfect music he had only just heard for the first time.

Aged just six, Wolfgang was already good enough to impress the Elector of Bavaria in Munich and Empress Maria Theresa in Vienna's Schönbrunn Palace. The next year, 1763, Wolfgang's audience became even more regal when he performed in Paris for King Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774) and for King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) in London. Amazingly, and still only 8 years old, Mozart published four keyboard sonatas in Paris. He was busy, too, on his first symphony and shortly after that his first opera. The latter work, titled La finta semplice (The Pretend Simpleton), was a comic opera first performed in Salzburg in May 1769. Here indeed was a raging new musical talent, but it came at a price. Feted for his talent and unable to acquire the necessary personal skills most children do in preparation for adulthood, Mozart was not quite a rounded individual. In the words of his first biographer, Friedrich Schlichtegroll:

For just as this rare being early became a man so far as his art was concerned, he always remained – as the impartial observer must say of him – in almost all other matters a child. He never learned to rule himself. For domestic order, for sensible management of money, for moderation and wise choice, in pleasures, he had no feeling. He always needed a guiding hand.

(Schonberg, 90)

The much more recent musical historian C. Schonberg gives the following scathing summary of Mozart's character and physique:

He grew up a complicated man with a complicated personality and an unprecedented knack for making enemies. He was tactless, spoke out impulsively, said exactly what he thought about other musicians (rarely did he have a good word to say), tended to be arrogant and supercilious, and made very few real friends in the musical community. He had the reputation for being giddy and lightheaded, temperamental, obstinate…In addition, he was not a glamorous figure physically. He was very short; his face, with a yellowish complexion, was pitted from smallpox; his head was too big for his slight frame. He was nearsighted, and had blue eyes that tended to protrude, a thick head of hair, a large nose, and plump hands.

(92)

Early Career

Wolfgang's musical education continued in Italy from December 1769. The Mozart family was certainly undaunted by the uncomfortable travel arrangements of 18th-century Europe, and they went on a Grand Tour that took in Milan, Florence, Naples, and Rome (where he received a Papal knighthood). Equally undaunted by his tender age, the ducal court at Milan commissioned Mozart to write a new (this time serious) opera, and he duly obliged with Mitridate, re di ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus). The work was performed in December 1770 to great acclaim.

Leopold Mozart has been criticised by some historians for touring incessantly with his son, but given his own musical background, it is likely he was not entirely motivated by financial gain. In addition, the exposure to different cultures in his youth greatly benefitted Wolfgang's music since the union of his natural talent with his sensitivity to the music of others "gave him a unique mixture of individuality and universality" (Arnold, 1209). At this stage of his musical development, Mozart was particularly influenced by the music of Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), whom he met in person, and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750).

Mozart was keen to work permanently at the court of Milan, but it was not to be, and so he returned to Salzburg where he was appointed the Archbishop's Konzertmeister, leader of the court orchestra, in 1772. This was Mozart's first salaried position. In 1775, Mozart's opera La finta giardiniera (The Pretend Gardener) was premiered in Munich. Keen to travel again, Mozart asked permission from his archbishop, was refused, and then dismissed. Heading for Paris, Mozart and his mother stopped at Mannheim in Germany en route. There Mozart fell in love with the soprano singer Aloysia Weber, but nothing came of it as he moved on to the French capital. Mozart struggled now to gain attention in Paris, although he was offered the minor post of organist at Versailles. He was no longer a child prodigy, but just another musician trying to make their way in the fickle music business. He was also a little cocky about his talent, which here and elsewhere often proved a stumbling block to the progression of his career. Mozart at least composed several new works, including the Paris Symphony (no. 31), but when his mother died suddenly, he returned to Austria in 1779, stopping at Mannheim where Aloysia made her indifference to the musician abundantly clear.

Through the late 1770s, Mozart had worked diligently at his court duties, composing a whole raft of symphonies, serenades, and concertos. In 1780, Munich again was a lucky city when he was commissioned for a new opera to be staged there. Mozart came up with Idomeneo, which expertly blended music and strong characterisation, it is considered his first great opera and was first performed in January 1781. Salzburg was becoming too limited a home for the composer now he had seen the grand capitals of Europe. Mozart was also not pleased with a new archbishop who had no interest in commissioning for church services the complex works he was now interested in composing.

Mozart in Vienna

In March 1781, Mozart left Salzburg for the wider career horizons offered by Vienna. In the Austrian capital, he earned a living teaching, composing chamber music, and giving private concerts to the wealthy where he tried out his new compositions, often conducting from his keyboard. In 1782, he wrote the opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Harem aka Seraglio) which was a success; its aria Martern aller Arten was especially liked. The opera was not without its detractors, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765-1790) noted, as many others did regarding Mozart's often complex works, that it had "too many notes" (Arnold, 1211).

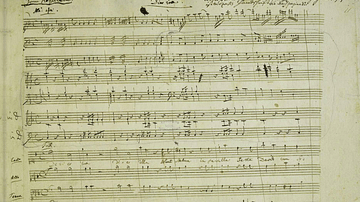

From around 1782, Mozart began to compose more innovative music in terms of the range of instruments involved. He utilised stringed instruments, horns, and the oboe but added to this traditional group flutes, clarinets, violas, bassoons, trumpets, and kettledrums. Mozart was concerned about people copying his music, and for this reason, he seldom gave permission for it to be circulated in printed form. Mozart himself kept detailed catalogues of his compositions. Still, life in Vienna for a freelance musician was hard.

Mozart married Constanze Weber (1762-1842), an amateur singer and younger sister of Aloysia, on 4 August 1782. Mozart described her rather unflatteringly: "She is not ugly, but by no means a beauty…She is not witty but she has enough sound common sense" (Schonberg, 97). Mozart's father did not approve of such a lowly choice, but there was nothing he could do about it. The couple had six children, but only two survived infancy: Karl Thomas Maria (1784-1858) and Franz Xaver Wolfgang (1791-1844), who became a musician and composer like his father. Wolfgang and Constanze's marriage seems to have been a happy one, and the stability it brought, along with a new life away from Salzburg, did the composer a power of good. As Schonberg notes, "1781 marks the period of Mozart's maturity, and virtually every work thereafter is a masterpiece" (99).

The Great Operas

It was always Mozart's ambition to excel in the field of opera. In 1786, he completed his opera Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), which was based on the play La folle journée, ou le marriage de Figaro by Pierre Beaumarchais. The play had been notorious for its comical attacks on aristocratic morality and had been banned in Vienna. Mozart's librettist was Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749-1838), the poet of the Vienna court. The story, told through four acts, has Figaro preparing to marry Susanna, who is being eyed by a Count, while Figaro must at the same time extract himself from a promise to marry another woman (Marcellina) if he does not pay off a debt. There are farcical misunderstandings, revealed identities, and a bit of cross-dressing, but, finally, a happy ending for all parties.

Mozart's opera is regarded as a masterpiece, but it was not well received by the Viennese at its premiere on 1 May 1786, the reaction perhaps coloured by Mozart's musical rivals, chief among them Antonio Salieri, the court composer. The opera fared much better in Prague in 1787, which encouraged Mozart to continue in this genre. For Don Giovanni and Cosi fan tutte or Thus Do All Women aka The School for Lovers (1790), Lorenzo Da Ponte was again responsible for the librettos. Don Giovanni, which tells the legendary story of the seemingly irresistible but ill-fated ladies' man better known as Don Juan, was a success in Prague, premiered on 29 October 1787, but again failed to inspire Vienna's music-lovers who once more described Mozart's music as "too advanced" and "difficult" (Arnold, 1212).

Cosi fan tutte tells the story, in two acts, of two soldiers, Ferrando and Guglielmo, who make a bet with Don Alfonso that their respective lovers (Fiordiligi and Dorabella) will remain faithful while they leave Naples for a time on active service. Both officers leave and then return in disguise to woo the lover of the other, all this with the involvement of the maid Despina who becomes a lawyer and arranges the marriage of the two couples. The disguised pair leave before the double wedding and return as themselves to chastise their sweethearts. Finally, all is forgiven, and the couples sing in praise of Reason. Performances of Cosi fan tutte were a success from January 1790 but were promptly curtailed in February when the emperor died and all opera houses and concert halls were closed as a mark of respect.

Despite Mozart's wider musical success he still struggled to gain recognition in Vienna. Although he secured a court appointment as the composer of chamber music in 1787, the position was not the one he had hoped for. The job was not well paid enough to meet his needs, although as he was known to dine on champagne and oysters, the composer needed a larger income than most musicians. Mozart's financial situation deteriorated significantly from 1788, so much so, he frequently had to ask his friends for money. Once again, Mozart was obliged to look elsewhere for a kinder reception to his work, but trips to Berlin and Frankfurt did not improve his poor finances. His wife required a cure at the famed waters at Baden-Baden, another drain on Mozart's resources. At least this time spent in German cities allowed him to better study the works of Bach, particularly his skill with contrapuntal devices.

Despite the lack of recognition, and with his health also failing, Mozart kept on composing symphonies, concertos, and dance music. He composed the opera La clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus), which was commissioned to mark the new emperor becoming the king of Bohemia at his coronation in Prague. The work premiered in September 1791. Mozart also reperformed his Coronation Mass of 1779.

One more opera came in September 1791: Die Zauberflöte or The Magic Flute. The two-act opera, with the libretto written by Emanuel Schikaneder, tells the story of Tamino who believes he has been rescued from a serpent by a bird-catcher called Papageno when in reality it was attendants of the Queen of Night. Tamino then falls in love with Pamina (or rather, a picture of her), daughter of the Queen. When Pamina is captured by the priest Sarastro, Tamino tries to rescue her armed with a magic flute, but she is guarded by a Moor called Monostatos. Tamino is ultimately successful, the captive and rescuer fall in love, and Tamino is initiated into the priesthood by Sarastro. Meanwhile, Pamina must endure several tests of her love. All ends well, and the Egyptian gods Isis and Osiris are praised in the opera's finale. The opera is packed full of references to the secretive Freemasons, probably more than the composer's fellow masons felt comfortable seeing on a public stage (Mozart had joined the Freemasons in 1784). The opera was a success, but the elaborate score – bursting with "catchy songs, entrancing arias and duets, spectacular display pieces and noble choruses" (Sadie, 190) – was again surprisingly complex for an audience primarily looking for just light entertainment.

Mozart's Later Works

Interspersed between the operas, Mozart composed many works of chamber music. "Perhaps his crowning achievement in chamber music is the pair of string quintets, K515 and 516 of 1787, works of a new richness, warmth and depth of feeling" (Sadie, 188). At the same time, Mozart's piano concertos of the mid-1780s, "forged a new kind of relationship between soloist and orchestra…the rich writing for the orchestral wind instruments helps give each concerto its particular character" (Sadie, 189).

In 1791, at last, recognition in Vienna came when Mozart was appointed the Kapellmeister of the city's St. Stephen Cathedral (although he never lived to take up the position). Mozart's last major work, Requiem, was commissioned by a Viennese nobleman to commemorate the death of his young wife. The commission was made in secret since the buyer wanted everyone to think he himself had composed the piece for his lost love. Mozart did not have time to complete the work, a task which was taken on by his pupil, Franz Süssmayr.

Mozart's Most Famous Works

The most famous works composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart include:

60 symphonies

24 string quartets

23 piano concertos

18 piano sonatas

16 Masses

5 violin concertos

Mitridate, re di ponto opera – Mithridates, King of Pontus (1770)

Coronation Mass (1779)

Idomeneo opera (1781)

Die Entführung aus dem Serail opera – The Abduction from the Harem (1782)

Le nozze di Figaro opera – The Marriage of Figaro (1786)

Don Giovanni opera (1787)

Cosi fan tutte opera – The School for Lovers (1790)

La clemenza di Tito opera – The Clemency of Titus (1791)

Die Zauberflöte opera – The Magic Flute (1791)

Requiem (1791)

In addition to the above, Mozart wrote concertos for wind instruments like the clarinet and many other individual pieces of chamber music and sacred works.

Death & Legacy

Mozart died in Vienna of ill health, likely a combination of kidney disease and rheumatic fever, on 5 December 1791. The composer did not leave enough money to avoid being buried in a simple unmarked grave in St. Mark's cemetery, and so the precise location of his remains is unknown today.

Mozart's music influenced many later composers, from Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) to Gioachino Rossini (1792-1768). His operas elevated the subgenre of comic opera to new heights, his piano concertos pointed the way to the majestic orchestral symphonies yet to come, and his chamber music revealed new possibilities of musical technique and expression, harmonic texture, and elegance. In the 19th century, Mozart was often called the Raphael of music, and like that Renaissance painter, he brought a new vibrant colouring and sheer joy to his artistic field. In short, Mozart staked a claim to being the greatest musician ever; those who follow have been presented with a target to equal or better if they can, but few indeed have got close.

Mozart's Requiem was played at the memorial service of Joseph Haydn in 1809. Haydn had once said to Mozart's father that "Before God, and as an honest man, I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me" (Arnold, 1209). Mozart continues to be immensely and almost universally popular, his music crossing cultural boundaries and appearing everywhere from film soundtracks to mobile phone ringtones (who has not heard Eine Kleine Nachtmusik joyfully interrupting a silence somewhere?). Perhaps the best explanation for this enduring popularity was given by the composer Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), who noted simply that "Mozart is sunshine" (Thompson, 78).