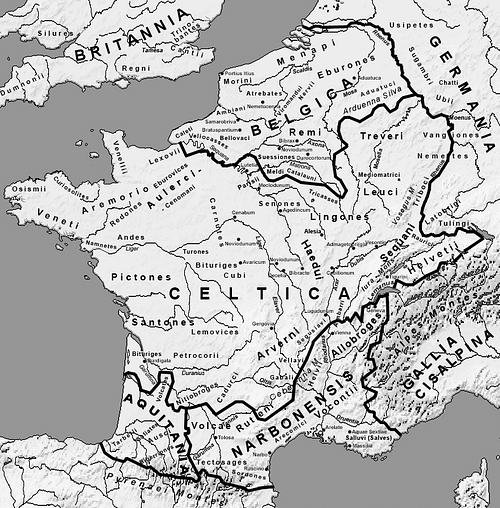

Ambiorix (c. 54/53 BCE) was the co-ruler of the Eburone tribe of Gallia Belgica (north-eastern Gaul, modern-day Belgium) who led an insurrection against Caesar's occupying forces in Gaul in the winter of 54/53 BCE. Nothing is known of his youth or rise to power; he enters and leaves history in the pages of Caesar's Gallic Wars which later historians then drew on for their own accounts of the uprising. Even his name is unknown as “Ambiorix” is a title meaning “Rich King” or an epithet meaning “King in All Directions”. However he came by that title, he actually shared the Eburone kingship with an elder leader named Cativolcus who seems to have been pressured into supporting Ambiorix's revolt and later regretted the decision. Ambiorix gained lasting fame for his clever deceit of the Roman garrison in Gaul under the command of Quintus Titurius Sabinus (died 54/53 CE) and Lucius Aurunculeius Cotta (died 54/53 CE) and the subsequent ambush which destroyed a Roman legion.

Caesar's Gaul

The Eburone Uprising was a complete surprise to the Roman forces as they believed they were on good terms with the tribe as a whole and with Ambiorix in particular. The Eburones were among the weaker tribes in the region and had become a client of the larger and stronger Aduatuci tribe to whom they paid tribute and surrendered hostages.

After Caesar defeated the Nervii and their allies at the Battle of the Sabis River c. 57 BCE, he reformed the tribal systems in Gaul, allegedly in the interests of equality and peace, but the reformation served his own purposes in decreasing the power and prestige of any one tribe. The Eburones profited from this as they were freed from their obligations to the Aduatuci, and Ambiorix personally benefited as hostages from his family were set free. The Romans, therefore, felt secure in their relationship with the tribe even though it was understood that they were still an occupying military force in the Eburones' land.

The Uprising

Another tribe in the region, the Treverians, resented the Roman occupation, and what little patience they had was lost when word was sent out by the Romans that all tribes would surrender a portion of their food supplies to the garrisons closest to them. A drought had made resources scarce enough for the tribes themselves, and the large Roman force wintering in the country made the situation more difficult.

The Treverian chief, Indutiomarus, suggested that Ambiorix should lead his people in an uprising to break the occupation. It is unknown how he convinced the Eburone king to take this on, but it is clear that Indutiomarus had no intention of engaging the Romans himself until he saw whether Ambiorix could succeed. It is also unknown how Cativolcus felt about the uprising at this point or how he was convinced to commit his half of the Eburones to the uprising, but in the winter of 54/53 BCE, the two kings led an attack on the Roman cantonment under the command of Sabinus and Cotta and the uprising had begun.

The Romans had built their fort with their typical efficiency, however, and the Eburones could not take it. Ambiorix understood that he would have to resort to a different tactic if he hoped to defeat his enemies and recognized how he could trick them into leaving their defenses behind.

The Trap is Laid

Ambiorix appeared at the gates of the Roman camp asking to parley. He assured the Roman commanders that he, personally, meant them only the best and was aware of the debt he owed Caesar for his kindness, but he had been compelled to attack by his countrymen who exerted tremendous power over his tribe. If it had been up to him, he said, he would never have thought of attacking Rome but, the way his position was, his people had as much power over him as he did over his people. The Gauls had set a date for a general uprising throughout the country, and he could not stand against their wishes and so had been forced to mount his assault on the camp but he meant them well and had come to warn them that a large force of Germans had been hired by the Gauls and was, even now, crossing the Rhine, so it would be in the Romans' best interest to leave their present fort – which could not hold against so large a force – and join their comrades at one of the other positions. He concluded his speech by promising them safe passage through his lands.

A war council was called in the camp after Ambiorix had left to choose the best course of action. Many argued that it was foolish to take the advice of an enemy who had just led an attack on them, but Ambiorix's apology seemed sincere. The Romans, as noted, thought of the Eburones as a friendly tribe but, further, they were also among the smaller and weaker, and it seemed irrational that they would choose to make war on Rome when they had no chance of success.

Ambiorix had promised them safe passage, and they would only have to march north 50 miles to reach the cantonment under the command of Quintus Tullius Cicero (102-43 BCE, the younger brother of the famous writer) or another commanded by Titus Labienus (c. 100-45 BCE), who had a larger force and was known as a brilliant cavalry commander. Either of these forts, they reasoned, was a better choice than remaining where they were and waiting for the Germans to reinforce the Gallic army.

The Battle

While the Romans debated what to do, Ambiorix was carefully preparing an ambush along the path he knew his enemies would have to take. He placed his warriors on either side of a ravine, two miles north of the cantonment. The Romans, meanwhile, had left their fort at dawn and were on the march just as Ambiorix had planned. He waited until half the legion had passed by his position and then gave the signal to attack.

The ambush took the Romans completely by surprise, and many were killed before they even realized they were under attack. They tried to move into formation for defense, but the ravine hampered their attempts and, all the while, javelins were raining down on them. Ambiorix sent his men to charge the Romans but they were cut down, and so he pulled them back and again ordered javelin barrages which the Romans could not defend against since the attack came from all sides and above them.

Ambiorix Rallies the Tribes

Ambiorix stripped the dead of their weapons and armor and ordered his troops quickly to march to the lands of the Aduatuci, where he told their chieftains of his great victory over the Romans and showed the weapons he had taken as proof. The Aduatuci joined the uprising, and then the Nervii did the same. Messengers were sent to other tribes with the news of the Roman defeat and more joined the cause. Ambiorix's force had now more than doubled, and he was confident they could easily take Cicero's camp.

Labienus had not sent any warning to Cicero about the uprising, perhaps because Ambiorix simply moved so quickly, and so Cicero's cantonment was caught by surprise when the Gallic forces came rushing out the tree line around the fort. Those outside the walls were killed instantly, but the gates were swiftly shut and secured and a defense mounted. Just as before, Ambiorix could not break through the walls and suffered heavy casualties in the attempt.

Since deceit and trickery had worked so well the first time, he decided he might as well try it again and asked Cicero for a parley. He told the same story he had at the other cantonment, professing his innocence and reluctance to attack, and urged the Romans to leave while they could before the Germans arrived.

Ambiorix assured them of safe passage in any direction they chose to take, but Cicero declined, stating it was not Roman policy to accept terms from an enemy in arms. If Ambiorix would cease hostilities and disperse his army, then Cicero would inform Caesar of the situation and they would wait for Caesar's decision and his justice. Ambiorix returned to his men and renewed the battle.

Messengers from the fort were quickly sent to Caesar, but they were caught and killed. A Nervian in the camp named Vertico, who was a friend of Cicero's, suggested sending one of his loyal slaves, a Gaul, who could easily slip through the lines. Promising the man his freedom if he succeeded, he sent him off with a message inside the shaft of a javelin and the slave delivered the message to Caesar later that same day.

Caesar's Response

Acting with his usual resolve, Caesar ordered a forced march of his troops to relieve Cicero, sending messengers to the officers of other cantonments to send him reinforcements. He quickly invaded the region of the Nervii where he took a number of them prisoner and learned the specifics of Ambiorix's uprising and the siege of Cicero's cantonment. He then chose a Gaul he could trust to deliver a message to Cicero hidden inside another javelin. The Gaul passed through the enemy lines and hurled the javelin over the walls where it went undetected for three days, but when it was finally noticed, it was brought to Cicero.

Cicero assembled his men and read them Caesar's message that they would soon be relieved but ordered them not to show any greater resolve or change their behavior in any way so as not to alert the enemy. Ambiorix was confident of another victory, since there was no evidence any word had reached Caesar and no hope of help for the garrison, but he became suspicious when he noted a renewed strength to the defense, and shortly after, his scouts brought word of Roman campfires a few miles away.

Ambiorix recalled his men from attack and ordered a quick-march on Caesar's position. Caesar saw them coming from a distance and set his own trap. He ordered a cantonment built on the high ground of a hill overlooking the valley from which the Eburones would come and directed that it be made as small as possible to give the impression that he had only a few soldiers instead of the 7,000 he commanded. He then instructed his men to appear frightened of the approaching army, make only short forays beyond the walls as though they anticipated an imminent attack, and to give no impression of a will to fight.

Ambiorix and his army were surprised to find so small a force sent against them. They considered Caesar a coward for stopping his march and thought the little fort a pitiful attempt at defense. To encourage the Eburones' confidence, Caesar sent out a few of his forces just so the Eburones could chase them back inside the walls. Once Ambiorix had formed his army across the hill to charge the fort, and Caesar saw they had nowhere to run for cover and defense, he ordered the attack.

Every gate of the tightly-packed fort was flung open and the Romans rushed down the hill, the cavalry in the lead, breaking the Eburone lines and throwing them into a confused panic. The Eburones suffered heavy casualties in the opening clash and those who survived were cut down as they tried to escape. The Romans continued to massacre anyone found on the hillside, but Ambiorix and a few of his closest men escaped down into the valley and evaded the cavalry sent to find and kill any survivors.

The Uprising Crushed

Caesar had the fort dismantled and then joined Cicero in his cantonment after sending word to Labienus of his victory. Meanwhile, Indutiomarus of the Treverians had finally heard about Ambiorix's earlier victory and marched his army to attack Labienus' position. He sent word to the Germans that a victory over Rome was certain if they would join him, but they declined the offer, noting how they had been promised such victories over Rome in the past. There is some evidence, however, that a German force was sent anyway to support the Gauls. Without waiting for German aid, Indutiomarus launched his attack on Labienus with complete confidence of victory.

Labienus, however, was equally confident; and with good reason. He had been told by a deserter from Indutiomarus' army what he looked like and where he would be positioned, and so Labienus gave orders to his cavalry that, once they were set loose on the Treverians, they were to ignore all other warriors until they had killed the Treverian king. As soon as the charge was given, the cavalry made straight for Indutiomarus and killed him. The loss of their leader demoralized the troops, and they broke ranks and fled. The historian Florus claims that the Germans, who may have been marching to support Indutiomarus, turned back to their own lands.

Whether Ambiorix was present at this battle is unclear, but shortly afterwards he deserted his tribe, with four of his bodyguard, and escaped across the Rhine into Germany. Caesar wanted him found, and would even invade Germany himself looking for him, but Ambiorix had vanished and was never heard from again.

Aftermath & Legacy

If he could not bring Ambiorix to face Roman justice, Caesar reasoned, he could bring Roman justice to Ambiorix's people. He enlisted a number of men from the defeated tribes in his armies through threats and rewards and controlled the tribes themselves through the same means. He then sent these warriors out as his vanguard to kill any of the Eburone they could find and, if possible, bring him Ambiorix. Fields and homes were burned and cattle slaughtered so that those who were not killed outright by the Roman forces were left to starve to death. Cativolcus, repenting of his support for the uprising, cursed Ambiorix for the destruction of his people and then poisoned himself.

Although relatively unknown for centuries, Ambiorix was made the national hero of Belgium in 1830 CE. After Belgium won its independence they followed the same course as other European nations and looked to ancient history for a suitable champion. Ambiorix was chosen for his resistance to Roman occupation and viewed as a freedom fighter, an image which suited the politics of the day, and the details of the extermination of the Eburones was ignored. A statue of the king was raised in the town square of Tongeren in 1866 CE, depicting him as a noble Gallic warrior, and still stands in the present day.

After the uprising of 54/53 BCE, the Eburones disappear from history just as Ambiorix himself does. Their memory was preserved, ironically, by Caesar in his Gallic Wars and then by other Roman historians using that work as their source. Caesar's Gallic Wars is sometimes viewed with skepticism by modern-day historians for inaccuracy and exaggeration, but it has been proven quite accurate in a number of instances, and so it is with the account of the Eburone uprising.

In 2000 CE a cache of 102 gold coins was discovered near Tongeren, Belgium dating to the time of Ambiorix's uprising. 72 of the coins are from the Eburone tribe, and all show that they were minted quickly as they were debased with copper so the gold would last longer and more coins could be made. This cache, known as “Ambiorix's Treasure”, is presently in the museum at Tongeren and supports Caesar's account in that coins were minted in Gaul only to pay soldiers and the debasing of these coins with copper suggests an imminent military action requiring quick cash. Further, the coins which do not come from the Eburones are from the tribes Caesar reports as their allies. Another cache of similar coins, largely of the Eburones, was found in 2008 CE near Tongeren and further supports Caesar's account of an uprising which was crushed so quickly the soldiers never had a chance to even receive their pay.