Tibetan sand mandalas are works of art created to encourage healing, peace, and purification generally as well as spiritual or psychological focus specifically for those creating and viewing it. A mandala (Sanskrit for "circle") is a geometric image representing the universe and a sand mandala, destroyed after completion, emphasizes the transitory nature of all things in that universe.

The image of the mandala first appears in the Rig Veda (c. 1500-1100 BCE), the earliest of the works known as the Vedas, the religious texts of Hinduism. It was then used by other schools of thought in India, including Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism. The first mention of a Tibetan sand mandala comes from The Blue Annals (Tibetan: deb ther sngon po), a work on the history of Tibetan Buddhism written by the Tibetan Buddhist scholar Gos lo tsa ba Gzhon nu dpal (also given as Go Lotsawa Zhonnu-pei, l. 1392-1481) between 1476-1478.

Mandalas are usually circles but can be squares or rectangles. They appeared in Buddhist artwork on canvas, as wall paintings, and in statuary as focal points of temples for hundreds of years before Tibetan Buddhist monks began the practice of creating sand mandalas. Unlike the permanent images, the sand mandala’s entire purpose is to be created only to then be completely destroyed, leaving no trace, symbolizing the transitory nature of existence and the Buddhist value of non-attachment.

Mandalas

The mandala image first appears during the Vedic Period (c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE) in India as a symbolic representation of the universe with the central deity of Brahman at the center. Hinduism (known to adherents as Sanatan Dharma, "Eternal Order") maintains that the universe was created by and also is Brahman who spoke the eternal truths of existence into the cosmos which resonated through time and were "heard" by sages in meditative states. These truths were transmitted orally until committed to writing during the Vedic Period and, among them, was the image of the mandala.

The mandala, like the words of the Vedas, was not thought to have been created by the human mind but received from the Universe, and this same understanding, more or less, would be maintained by other belief systems which used it in India except for the materialist school of Charvaka. Charvaka, which denied the existence of any higher power, used the mandala to express the material nature of the world without reference to a deity or afterlife, but Jainism, and then Buddhism, both created theistic mandalas. Scholars Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. comment on the early evolution of the image:

Mandalas may have begun as a simple circle drawn on the ground as part of a ritual ceremony, especially for consecration, initiation, or protection. In its developed forms, a mandala is viewed as the residential palace for a primary deity – located at the center – surrounded by an assembly of attendant deities. This portrayal may be considered either a symbolic representation or the actual residence; it may be mentally imagined or physically constructed. The latter constitutes a significant and highly developed contribution to the sacred arts of many Asian cultures. (523-524)

The mandala in Buddhism became a sacred image, which conferred blessings and spiritual insight on the creator as well as an audience. The individual artist-monk who creates the image is understood to be receiving it from a higher source and so is blessed with that connection to the Divine as well as the discipline and focus necessary to render the image in the physical world. Paintings or sculptures of mandalas became objects of veneration in that they were believed to accurately depict the nature of existence, but an understanding of that nature would vary with individual interpretation. No two people viewing a mandala might come away with the same meaning and, because of this, the mandala was (and is still) thought to be a kind of spiritual mirror reflecting each viewer’s psychological or spiritual state.

The contemplation of a mandala is thought to enable spiritual awakening and psychological/emotional growth and, in Tibetan Buddhism especially, is believed to quicken one’s realization of the nature of the world and speed the process of enlightenment. This appreciation of the mandala in Tibetan Buddhism differs from other Buddhist schools which emphasize a slower and more gradual process toward full awakening.

Buddhism & Non-Attachment

According to Buddhist tradition, Buddhism was founded by the Hindu prince Siddhartha Gautama (l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE) after he renounced the trappings of the world and became the Buddha ("the enlightened one"). Siddhartha became the Buddha upon fully realizing that people suffered because they insisted on permanent, unchanging, states of being in an ever-changing world. Resisting change, and clinging to illusions of permanency, humans condemned themselves to lives of suffering, which, because of their attachment to illusion and inability to recognize truth, led to an endless cycle of rebirth, death, and rebirth, an infinite round of suffering.

He established his Four Noble Truths on the basic, foundational recognition that life is suffering but claimed there was a way to live without this kind of endless pain by practicing non-attachment:

- Life is suffering

- The cause of suffering is craving

- The end of suffering comes with an end to craving

- There is a path which leads one away from craving and suffering

One could attain a more harmonious relationship with the world and oneself by following the precepts of the Eightfold Path:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

Buddha referred to this path as the middle way in that one maintained personal balance by adhering to a philosophy and behavior in between the attachment to the things of the world and the strict renunciation of such things as practiced by aesthetics and adherents of Jainism. One began one’s walk by realizing that everything in one’s life was fleeting and without lasting meaning. One could still enjoy one’s family, friends, and possessions but only by recognizing their transitory nature.

One’s personal accomplishments, also, were to be valued but only with the understanding that these, also, were fleeting and may not survive beyond one’s death. One should, therefore, perform any action the best one could simply to do so, not in the hope of any lasting physical gratification or reward. By following this philosophy, one could engage in living without fearing loss, experiencing its pain, or longing for what one once had.

After Buddha’s death, his teachings were developed by his disciples, possibly beginning with the schools of Sthaviravada (often cited as an early Theravada school) and Mahasanghika (a possible precursor to the Mahayana school) but eventually established as three main schools:

- Theravada Buddhism (The School of the Elders)

- Mahayana Buddhism (The Great Vehicle)

- Vajrayana Buddhism (The Way of the Diamond)

All three schools claim to represent Buddha’s original teaching and, objectively, no one of them is considered more authentic than the others, though their adherents would disagree. The first two emphasize the importance of renunciation and non-attachment before one begins the observance of the Eightfold Path, while the third claims one will naturally lose attachment to transitory pleasures as one recognizes one’s true nature and comes to appreciate lasting values.

Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana Buddhism developed in Tibet and was systematized by the sage Atisha (l. 982-1054 CE) so it has come to be known as Tibetan Buddhism. The name Vajrayana translates as "adamantine vehicle", "thunderbolt vehicle", or "diamond vehicle" because of the school’s belief that enlightenment arrives suddenly as one puts in the necessary work.

This is the major difference, among others, between Tibetan Buddhism and the Buddhism of the other schools (although, technically, Vajrayana Buddhism is part of Mahayana Buddhism). Theravada and Mahayana schools both emphasize the steady process of discarding what is ultimately meaningless and embracing lasting values as one realizes one’s own Buddha-nature and awakens. Vajrayana emphasizes the concept of Tat Tvam Asi – "Thou Art That" – one is already what one wishes to become, one only has to realize it.

There is, therefore, no need to renounce one’s family ties or various habits because, as one proceeds along the path, enlightenment will fall like a thunderbolt, and one will recognize the adamantine nature of true reality and lose interest in illusion. Instead of focusing on what one must reject to attain enlightenment from the start, one centers attention on what one wants to embrace. The Dalai Lama (often referenced as the spiritual leader of Buddhism, though he is only the spiritual head of the Vajrayana school) emphasizes this concept in many of his lectures when he counsels people to simply pursue the best values and behavior of their own religious traditions instead of feeling the need to convert to Buddhism to live an awakened life. As one works on one’s own spiritual development, the positive energies one generates encourage the same in others, without proselytizing, and every action one performs in accordance with the principles of the Eightfold Path benefits others as well as oneself.

The Tibetan Sand Mandala

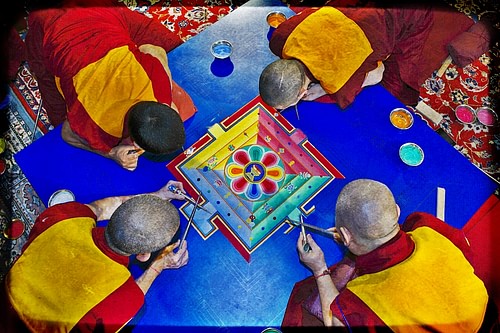

All of these values and concepts are epitomized and expressed through the Tibetan sand mandala. The image is made by monks who have devoted their lives to Buddhist principles which they live in the creation of the mandala that will then be destroyed. Their focus is on the act itself, not a lasting reward for that act, and after creating a thing of beauty, they destroy it in a gesture of non-attachment to their efforts and to the physical manifestation of those efforts.

In the creation of a permanent mandala for a temple or shrine, five steps are observed:

- Preparation for the work – the material is cleaned and blessed through prayer and ritual, as is the space in which the work is to be done

- Drawing the design – the mandala is drawn on the material using chalk or clay

- Painting – the mandala is painted following the design using pigments made of minerals

- Shading and accent – pigments made of organic materials are used to add depth to the image and highlight various aspects

- Finishing – the mandala is rubbed gently with dough to pick up any stray bits of pigment, dusted with a dry cloth, and gold gilt is added to aspects of the piece to emphasize importance.

A Tibetan sand mandala follows these same steps but with significant differences throughout.

Preparation for the Work – a location is chosen for the mandala. It can be anywhere – a schoolroom, a temple, a museum, a university, a conference room in a hotel, or a place of business – and an area selected in that place is purified through incense and made sacred space through ritual. The team of monks who will create the mandala is present for the ritual as is a senior monk usually responsible for the design.

Drawing the Design – after the design has been chosen, it is drawn in chalk by the monks on the area or on a board they have brought which was blessed during the ritual. The design might feature Buddha in the center or the Tibetan Star or one of the many Buddhist deities and may be circular or square. The design begins at the center and the monks work outwards. Unlike a permanent mandala where there is one artist, two or more monks draw the design.

Painting – instead of paint, the monks use colored sand and, beginning at the center, follow the lines of the design by laying down the sand in delicate outline. This is usually done through a tool called a chak-pur, a metal cylinder a little longer and fatter than the average pencil with a large opening at one end and a narrow opening at the point. The chak-pur is filled with a certain amount of single-colored sand the monk applies to the design by tapping the side with a small, metal rod. Some monks prefer not to use the chak-pur and apply the sand entirely by hand, scooping up small palmfuls and dispensing it onto the image between thumb and forefinger.

Shading and Accent – once the initial sand is applied, bringing the design to life, the spaces in between the lines are addressed with more sand and then with designs accenting the meaning of the piece. The monks work in teams, usually two to each of four sections, starting always in the center and working outwards.

Finishing – once the mandala is complete (which can take up to two weeks, sometimes longer), it is left for people to interact with and learn from. At a time specified in advance, the monks reconvene at the mandala and perform a closing ritual, which includes blessings, prayer, and purification. The lead monk then draws a line vertically through the mandala and then another horizontally either with a ritual object or his finger, ruining the work. The other monks then participate in its destruction, pushing the sand around into a heap. Depending upon the circumstances of its creation, some of the sand is poured into little plastic bags, which are given to spectators and guests as a blessing, but most of the sand is brought to a running stream where it is ritually poured into the waters and swirls away to bring blessings to all the world.

Conclusion

The monks train for years before they are allowed to participate in the creation of a Tibetan sand mandala. They learn to draw and paint and the skills necessary to apply the sand properly, but more importantly, they must learn what the mandala means to them, the form itself, and what it provides them with spiritually. They must also understand the power of the form for others, what it is able to give to the world at large, and they also must be able to fully embrace the value of non-attachment in creating something for others, which may not even be appreciated, and that will not last.

The design most often followed is of a grand palace with the throne room in the center where the Buddha sits quietly in harmony. There are four entrances to the throne room facing the four cardinal directions. Outside of each entrance, there is a deity or spirit – sometimes these are all benevolent, sometimes not – and between these entrances are symbols representing the currents of time and change or images of other deities and spirits.

The choice of what specific images will appear in the mandala is dictated by the occasion it is created for as received by the senior monk who will suggest it. The entire mandala is multicolored and vibrant, suggesting the life force and Buddha-nature within all creatures, and its outer rim is carefully fashioned to suggest the constant motion and change of the universe as contrasted with the throne room which is still and at peace.

Everything in the image outside of the throne room is in motion in most mandalas of this type, and the viewer is invited to begin at the outside and work toward the center. This seems to have always been how the mandala, in any form, was most often meant to be interpreted, but it received greater attention in the 20th century through the work of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung (l. 1875-1961), who recognized the image of the mandala as a universal archetype which appears, in one form or another, in the cultures around the world throughout history.

Jung defined the mandala as "an instrument of contemplation" which led a viewer from the external world of distraction toward the internal world of the center where one found stability and peace (Archetypes, 356). The mandala, Jung noted, could be understood as a representation of the self. As one moves through life, it is easy to become caught up by all the transitory distractions one encounters, and unless one recognizes them as fleeting diversions, one believes them to be reality, takes them seriously, and continues on at their mercy.

If one moves steadily toward one’s center, however, one recognizes one’s true self, distinct from the trappings of one’s life, and can come to know who one truly is rather than responding to reflections of oneself in the lives of others and the circumstances of one’s life. Knowing oneself provides stability and a point of reference from which one can recognize what is worth one’s time and effort and what is not. As one comes to recognize how easily people can become distracted and lost, one can better appreciate others and their struggles and so one’s own journey toward self-knowledge also benefits them.

The Tibetan sand mandala takes this recognition one step further by demonstrating the whole of life in its brief existence. The mandala ends in its own destruction – after it is dismantled, and the area cleaned, there is no trace it ever existed – just as people are born, live, die, and disappear, continuing afterward, on earth anyway, only in the memory of those whose lives they touched.