Tea, still probably the world's most popular prepared beverage, was first drunk by Chinese monks to aid meditation and those who valued its medicinal qualities, but it quickly grew in popularity, spreading to other East Asian cultures, especially Japan. An elaborate ceremony for its preparation and consumption developed which sought to foster the appreciation and beauty of life's simple luxuries. In addition, tea drinkers were able to discreetly display their good taste and wealth not only by serving what was a relatively expensive commodity but by reserving their very best porcelain for drinking it.

With books written by tea experts on how to conduct oneself and appreciate the tea fully, along with poems eulogising the beverage, tea drinking was developed into an art form. The tea ceremony, thus, became a simple way to escape for a moment the tribulations of one's often hectic everyday life, a function drinking tea still has for many people today.

Tea in Mythology

In both Chinese and Japanese tradition, the discovery of tea is credited to the Indian sage Bodhidharma (aka Daruma), the founder of Chan Buddhism, a precursor of Zen Buddhism. Bodhidharma, travelling to spread the word of his new doctrine, founded the Shaolin temple in southern China (Shorinji to the Japanese). There he meditated while sat facing a wall for nine long years. At the end of that period his legs had withered away and, just on the verge of reaching enlightenment, he fell asleep. Enraged at missing this last step, he ripped off his own eyelids and threw them to the ground. From these a bush grew, the tea plant.

A Medicinal Drink, Stimulant & Commodity

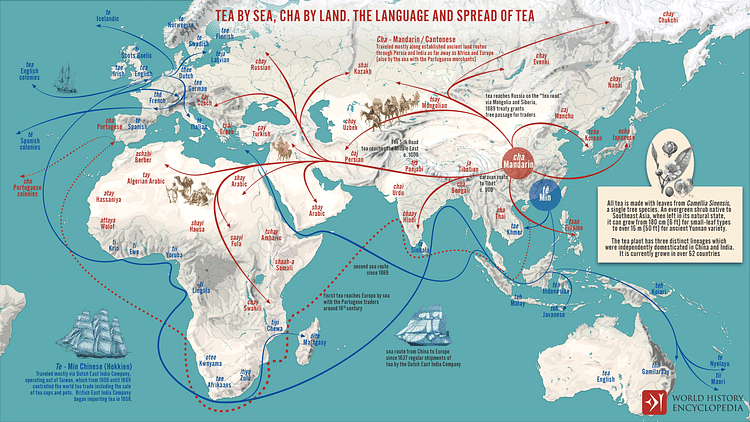

Tea goes by various names: cha in Chinese and Japanese or chai in Hindi and Urdu. The English name probably derives from the pronunciation of the drink (the) in the province of Fujian, south-east China. The drink is made by adding hot water to the young leaves, leaf tips, and leaf buds of the plant Camellia sinensis which is native to south-west China.

The drink was first used by Buddhist monks from around the 2nd century BCE to support them while they meditated and to ward off sleep. Tea was also thought to possess medicinal qualities, curing a hangover being one of them. By the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) tea had spread beyond the monasteries and become a popular drink with the gentry who were the only people who could afford such an expensive drink. Tea became an important element of the economy, with large estates in the south-east of the country cultivating the plant and providing the government with valuable tax revenue on its sale. Tea merchants, who were now exporting it to other Asian countries, were amongst the richest businessmen in China.

Impact on Culture

The trend for tea-drinking also created a boom in the fine ceramics people preferred to use to brew, mix, and drink it from, and the elegant jars they used to store their tea leaves in. One of the most highly-regarded producers of teapots was Yixing in Jiangsu province. In a culture where ostentatious displays of wealth were frowned upon as vulgar, the use of a simple but expensive ceramic tea bowl was all that was needed to show one's prosperity.

Tea drinking became such an integral part of the Chinese culture that it began to appear in art and literature. One famous poem by Lu Yu appeared in his 8th-century CE treatise on the forms and conventions which should be applied when drinking tea. The poem is a thank you note after Yu had received a gift of a packet of freshly picked tea.

To honour the tea, I shut my brushwood gate,

Lest common folk intrude,

And donned my gauze cap

To brew and taste it on my own.

The first bowl sleekly moistened throat and lips;

The second banished all my loneliness;

The third expelled the dullness from my mind,

Sharpening inspiration gained from all the books I've read.

The fourth brought forth light perspiration,

Dispersing a lifetime's troubles through my pores.

The fifth bowl cleansed ev'ry atom of my being.

The sixth has made me kin to the Immortals.

The seventh is the utmost I can drink -

A light breeze issues from my armpits.

(in Ebrey, 95)

Spread

Along with other cultural practices, tea drinking was passed on from China to neighbouring East Asian countries such as the Silla kingdom of Korea but nowhere did it become more popular than in Japan from the 8th century CE. In Japan, too, it was Buddhist monks who first drank tea, and it did not become fashionable until around 1200 CE. As China cultivated better tea plants than those available in Japan, these too were imported and not just the cut leaves.

In Japan, tea was usually prepared by pounding the leaves and making a ball with amazura (a sweetener from grapes) or ginger which was then left to brew in hot water. Eventually, again from 1200 CE, specialised tea schools were opened and people reserved their finest porcelain for tea drinking.

The Tea Ceremony

Although the ritual and ceremony which developed when serving tea originated in China, it is the Japanese who have made it synonymous with their culture. The Japanese Tea Ceremony is called chanoyu, meaning 'hot water for tea', or chado or sado, meaning 'way of the tea'. Tea parties began as rather rowdy affairs where guests tried to guess the type of tea they were drinking but the 15th-century CE shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa put a stop to all that and made the whole thing a much more sober and subdued event, offering the ruling class a perfect setting for discrete conversation on sensitive subjects.

The ceremony typifies the Japanese aesthetic principle of wabi, which is the value given to the appreciation of beauty and simplicity in everyday things. The application of wabi to the tea ceremony is credited to the 16th-century CE tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591 CE). Rikyu was master of the tea ceremonies of the warlords Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and he also promoted the use of carefully arranged flowers (ikebana) to create just the right atmosphere of calm when drinking tea. Rikyu's masters did not always listen to him it seems for Hideyoshi famously threw a tea party for 800 guests to celebrate his victory in Kyushu in 1587 CE. Still, the monk had more success with subsequent generations as the tea ceremony gradually became more and more genteel and intimate.

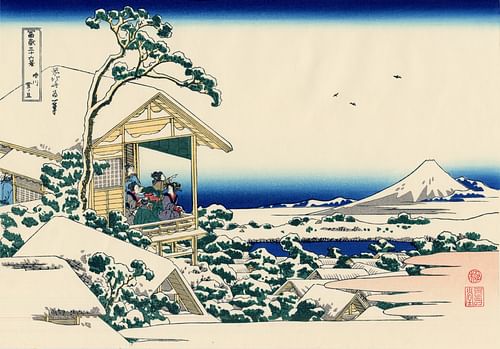

The first thing to do when drinking tea was to put oneself in the right place and for the Japanese that was the dedicated chashitsu or tea room, also known as a sukiya or 'house of the imperfect', alluding to the structure's original simple architecture and basic materials. Roofs were in bamboo and thatch, supporting columns were unworked, and the walls made of earth. This rustic building was quite separate from the main residence (immediately stamping an aristocratic requirement on the ceremony as only those with money could obviously afford such a thing). Thus, the drinker or drinkers were immediately detached from the everyday living space and so, by extension, their everyday lives. Three original tea rooms still exist today and are listed as National Treasures of Japan. They are to be found in the Myoki-an of Yamasaki, within the Shinto shrine of Minase-gu, and at the Saiho-ji monastery in Kyoto.

The tea room was small, only three metres square usually; Rikyu is credited with downsizing the previously larger rooms. It had minimal decor and services: a toilet and a tsukubai, which consists of a stone basin (chozu-bachi) outside for cleaning the hands before entering along with several irregular stones placed nearby in an aesthetically pleasing manner. Another feature is a stone, free-standing lantern, also outside. Ideally, the tea room should stand in its own small garden (cha-niwa) which has a stepping stone path (tobi-ishi) leading from the main house. The desired greenery was evergreens rather than flowers, and moss or grass underfoot to begin the calming effect of the ceremony before even entering the tea room.

The doorways of tea rooms were usually small, only around 90 cm (3 ft) high, which was meant to show that all were of equal status once inside. Some historians believe the door prevented swords being taken into the tea room in another way to demonstrate rank and occupation were to be abandoned while drinking tea. Windows and paper screens gave plenty of light to the interior.

The details and etiquette of how the tea was brewed and served using a special ladle or the restrained gestures one should employ all depended on which school of tea ceremony one adhered too, and there were many. Water was usually boiled over charcoal in an iron kettle, and the tea was strong, green and bitter. Common, too, to all ceremonies was the requirement to use the finest porcelain one could, especially the tea bowl or chawan, actually used to drink from.

Later History

Tea was so widely consumed and had become such a big business by the 16th century CE that it eventually interested European traders, notably the Portuguese and Dutch. Tea was introduced to Europe in 1607 CE and, by the 19th century CE, the drink had become so popular in Europe that drinkers could choose from Chinese, Indian, and Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) tea. Tea from the latter two countries was stronger and so was preferred, especially with the British who had encouraged its cultivation in colonial India. Even so, tea made up 80% of China's total exports to Europe in the early 19th century CE.