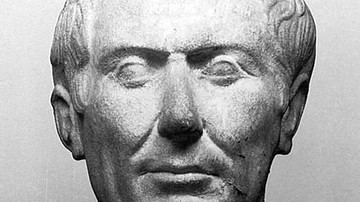

Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) first assumed the role of dictator in 49 BCE, however, once he had secured his election as consul for the following year, he resigned after 11 days. After defeating Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, he was once again appointed dictator, this time for a year. This was followed by a ten-year appointment in 46 BCE, then he assumed the power of dictator for life shortly before his death in early 44 BCE.

Political & Military Success

Born into a patrician family on 13 July 100 BCE, Caesar began his political career in 73 BCE when he was elected to a vacancy in the College of Pontiffs upon the death of his mother's cousin Gaius Aurelius Cotta. After time spent as a military tribune, he entered the cursus honorum, the sequence of Roman government offices in 69 BCE, serving as a quaestor in Further Spain: the position garnered him a much-desired seat in the Roman Senate. He was elected an aedile in 65 BCE and a praetor in 62 BCE. A year earlier, in 63 BCE, he was named pontifex maximus, or the chief priest of the College of Pontiffs. It was an appointment that provided him with a house in the Roman Forum. However, it was a candidacy steeped in both controversy and bribery. In 60 BCE, he joined Gnaeus Pompey (106-48 BCE) and Marcus Crassus (115-53 BCE) to form a political alliance: the First Triumvirate. Despite the objections of the more conservative optimates, Caesar became a consul in 59 BCE.

For the better part of the next decade, he commanded his legions in the conquest of Gaul and on an invasion attempt in Britain. Despite a renewal of their alliance, growing tension between Pompey and Caesar escalated. Pompey was jealous of Caesar's success and fame, while Caesar wanted a return to politics. As Pompey grew to become the favorite of Rome, Caesar emerged as a pariah. On 7 January 49 BCE, he was named an enemy of the state by a decree from the Senate. Three days later, Caesar, with only one legion, crossed the Rubicon and thereby initiated a civil war. Dennison wrote that by crossing he went from legality to illegality and "from the status of heroic outlaw to traitor" (34). Although attempts were made to prevent war, Pompey eventually took a hasty exit from Rome. Caesar assumed the emergency powers of a dictator for eleven days, long enough to secure his election to another consulship.

Civil War & Dictatorship

Caesar chased the always elusive Pompey across Europe. Finally, in 48 BCE, he defeated his former ally at the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece. Upon returning to Rome, he again was named dictator; his time for a year. It had taken three years, but he fought and defeated the Republican forces of Cato the Younger (95-46 BCE) at the Battle of Thapsus, the army of King Pharnaces II of Pontus (c. 95-47 BCE), and the anti-Caesar forces of Sextus Pompey in Spain. This time, upon entering Rome, Caesar was greeted with open arms. It was a different day, and the people had grown tired of war; they simply wanted peace. He was hailed as a hero. Honors were heaped upon Caesar: a Roman triumph was celebrated for each of his campaigns: Gaul, Pontus, Egypt, and Africa. He was called a liberator and the father of his country (pater patriae). A new Temple of Venus was dedicated, and he treated the citizenry to a festival, games, gladiatorial contests, and stage plays.

In September of 46 BCE, he was again named dictator, but this time for ten years. However, in February of 44 BCE, (one month before his death) he was named dictator for life (dictator perpetuo). It was an unprecedented appointment and something many would soon rethink. He "accumulated an extraordinary list of honors, not a few of which were unprecedented, and too many of which suggested that he aimed at regal or divine status" (Rosenstein et al., 208). According to Tom Holland in his Rubicon, no one knew what Caesar planned to do because no one knew how the Roman Republic was to be healed of the wounds of civil war.

As Caesar's power grew and it became obvious that he was not going to return Rome to its glory of the old republic as promised, the Roman Senate decided that it was necessary to rescind some of the powers they had granted. The Roman nobility, naïve or not, could not imagine Caesar refusing, but according to Barry Strauss, "Caesar had no intention of playing the senators' games" (The Death of Caesar, 31). He no longer cared about the opinions of the Senate. While many wanted Rome to return to a government of laws, Caesar disagreed, believing that "only his genius offered the people of the empire peace and prosperity" (ibid, 32).

In his Masters of Command, Strauss wrote that Caesar wanted to dominate Rome and gave two reasons why he crossed the Rubicon:

- he was defending the powers of the tribunes, who he believed were the true representatives of the common people

- he thought of his own personal rank and honor

Even though he later expanded the size of the Senate, he believed it had kept Rome from making necessary reforms; his opponents, the optimates, disagreed. To them, the Senate had made Rome "wise and free." Oddly, while he did not respect its authority, it was the Senate who had granted him all of his honors. Caesar believed in his own intelligence and felt that only a man of wisdom and talent could initiate the necessary reforms. And, in his mind, he was that man. Although Caesar wanted the powers of a king, he did not want the title and refused to be addressed as such. While his title of dictator-for-life violated the Roman constitution, he believed it served the public good. His "monopoly on power and glory made him an anathema to the men who felt right in deeming themselves to be his peers" (Rosenstein et al., 208).

Reforms

According to Philip Freeman in his book Julius Caesar, in 46 BCE, Caesar began a revolution that would change Rome forever. Owing to his time as a military commander, Caesar had demonstrated that he was not one to sit idly, and this belief can best be seen early in his role as a dictator. During that time, he initiated a number of civic and social reforms, affecting almost every facet of daily life in ancient Rome. While these reforms made him popular among the commoners, they brought panic to many of his enemies and even some of his friends.

Since previous censuses had yielded inaccurate figures, one of the first of these reforms was to conduct a proper census; auditors were sent door-to-door throughout the city. A correct census was essential; the city had been ravaged by Roman warfare and added to this were years of ineligible residents obtaining free grain, which was intended for the poorest of the Roman citizenry. In the end, the grain dole was cut in half, saving money, but the new census figures shocked Caesar, and he became concerned about the overall decline in the city's population. To encourage larger families and potentially provide manpower for the Roman army, Caesar not only offered grain supplements but also prohibited any Roman male between the ages of 20 and 40 from being absent from Rome for more than three years; of course, members of the military were exempt.

Suetonius (c. 69 to c. 130/140 CE) wrote that "In his administration of justice he was both conscientious and severe" (20). This was evident in his treatment of the Senate. Although he had a deep disdain for its authority, Caesar realized that he needed the Senate; he could not rule alone. Although "it meant the traditional ruling families became a minority in Rome's most distinguished body" (Freeman, 336), he increased the number of senators to almost 900. Suetonius believed that Caesar had brought the Senate up to strength. Soldiers, sons of freedmen, and foreigners who had served him well were made senators.

He also increased the number of quaestors, aediles, and praetors. To increase the number of middle-class professionals, he granted citizenship to physicians and teachers who settled in the city. He encouraged large farm owners to hire more free laborers, becoming less dependent on slave labor. He banned auctioneers, grave diggers, fencing teachers, pimps, and actors from serving as magistrates. Lastly, he excluded members of the lower class from serving on juries. Caesar extended Roman citizenship to leading citizens of Gaul and Spain and established citizen colonies. Farmers, skilled craftspeople, and professionals were invited to settle in Italy, while idle poor from the Roman slums were given incentives to move to one of the new colonies in Spain, Gaul, Africa, or Greece. With the city of Rome suffering from violence and corruption, Caesar cleaned up the dangerous city streets.

His most famous reform was to the calendar. Suetonius wrote that the pontifices had allowed it to fall into such disorder that the harvest and vintage festivals no longer corresponded with the appropriate season. Caesar used his position as the pontifex maximus for Rome to switch from the lunar to the solar calendar.

Among the other reforms initiated by Caesar was his ban on all clubs and guilds not sanctioned by the government, although organizations of ancient standing were allowed to continue their meetings. He built a new public library filled with Greek and Latin works where Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BCE) was named the first curator in charge of collecting and cataloging, Plans were also made to codify the immense volume of Roman law: something that was finally completed under Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565). Among his plans were a new harbor at Ostia and to drain the Pontine Marshes and Fucine Lake. He imposed heavy duties on foreign luxury items and placed guards throughout the city to seize illegally imported goods. The guards were even sent into private homes.

Assassination

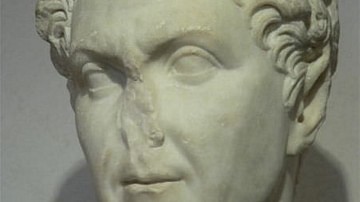

While many in Rome accepted Caesar's arrogance, they came to believe he was becoming more of a divine figure than a ruler. "Even Caesar's positive social reforms of which there were many, because they were imposed by order, rankled" (Rosenstein et al., 208). On the Ides of March, 15 March 44 BCE, he was assassinated by a group of conspirators led by Marcus Junius Brutus (85-42 BCE). The assassination of Julius Caesar did not return the glory days of the past; instead, it brought about another civil war.