The traditional house of ancient and medieval Japan (1185-1606 CE) is one of the most distinctive contributions that country has made to world architecture. While the rich and powerful might have lived in castles and villas, and the poor lived in rustic country houses or cramped suburban quarters, a large number of medieval Japanese in-between lived in what became the quintessential Japanese home. Features which continue to be popular today include rice-paper walls, sliding doors and foldable screens, a floor of tatami mats and futon beds, and a minimalist approach to interior decor.

The Japanese Approach

Most buildings in Japan, both long ago and today, need to resist annual typhoons and occasional tsunami and earthquakes. On top of that, the summers can be very hot, the winters cold, and there is an annual season of heavy rain. The ancient and medieval Japanese found a simple solution to these difficulties: do not build to last. Rather than resisting the environment, houses were, therefore, built to follow its whims and, if the worst happened, they were designed to be easily rebuilt again. This approach also means that very few old buildings have survived in Japan today, but the architectural style and tricks certainly have.

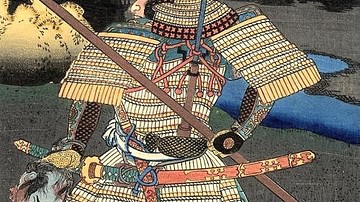

Japan had a very stratified class system and architecture was one of many ways authorities used to maintain the status quo and reinforce the idea that everyone has their correct station in life. There were specific sumptuary laws which prohibited commoners owning houses of the style favoured by samurai, for example. The samurai class were much impressed with the Zen-influenced architecture of Buddhist temples, and they imitated the austerity and minimalism of this in their own homes. These trends would eventually filter down into the homes of other classes. One area the lower classes did match their superiors was in their sparse furnishings, but this was usually due to a lack of means rather than aesthetics.

Exteriors

Prior to the modern era, Japanese domestic housing (minka) could be divided into the following four categories:

- farmhouses (noka)

- fishermen's houses (gyoka)

- mountain houses (sanka)

- urban houses (machiya)

While all of the above had regional variations depending on local climate and the availability of materials, some common features may be identified. Those homes in rural areas, for example, were typically one-storey, built of wood, and raised off the ground by posts. They had a floor of hardened earth (doma) where cooking was done and had another area with a raised wooden floor for sleeping. Urban houses were smaller than the other categories because of the general lack of space in cities, but this problem was solved by building upwards and so many machiya had two floors. It was quite common for urban houses to be attached to each other and for toilets and a water source to be shared between neighbours. Many city houses were also the proprietor's business premises - a small workshop or shop. Windows were protected by sliding wooden panels (amado) which acted as shutters. A roof was made weatherproof by having a gable and then covering it with thatch, tiles or bark shingles. Roofs had overhanging eaves and the main entrance had its own covering (genkan).

The architectural style of finer domestic houses became known as shinden-zukuri in the medieval period and an important part of it was the blending of home and garden. The garden was designed to be viewed from various points in the house by moving back sliding windows and walls. The garden itself was typically landscaped and might contain trees, flowering shrubs, groups of special grasses, areas of moss, artificial hills, water features, and a rock garden, although it was not necessarily a large space as all of these features could be miniaturised. Larger gardens often had their own rustic tea house (sukiya), a dedicated space for the Japanese Tea Ceremony. Initially, the shinden-zukuri style was only enjoyed by the samurai class.

Interiors

The sitting room (zashiki) was first seen in the homes of samurai who, as members of the upper class, were required to give audiences to their vassals and officials. For the same reason, one area of the room's floor may be slightly raised (jodan-no-ma). The idea then spread to the homes of commoners in the late medieval period. There might be a built-in desk (tsukeshoin) facing the wall in this room, another hangover from the samurai's house.

Interior paper-covered sliding doors (fusuma) were made by pasting paper (or even sometimes silk) onto a delicate wood-lattice frame. Doors were closed or opened to play with the size of rooms and windows were often designed in the same way. Above both, one might have a transom or ramma, which was a carved wooden rectangle which provided more light and air to the room. Internal space could be further divided using freestanding paper screens (shoji) which could be of the folding type (byobu) or consist of a single panel (tsuitate). The paper used in screens was usually thinner and more translucent than that used in walls. More rustic houses might also have bamboo or reed blinds (sudare) over the windows.

The wooden floor of a traditional Japanese house is covered with rectangular tatami mats which are made from straw but with a top layer of woven grass. Tatami date back to the Heian period (794-1185 CE) and both the thickness and the pattern of the weaving of tatami mats was an indicator of status in medieval Japan. Although not exactly standardised across Japan in terms of size, the number of tatami mats it was possible to lay out in a single room became a common way to measure floor space. The size of a single tatami in the medieval period was 85 cm x 1.73 m (2.8 x 5.7 ft). Heating was provided by portable charcoal braziers (hibachi) or a fixed central hearth and, in the medieval period, lighting was provided by either wooden torches or oil lamps.

Furniture

Furniture was sparse in Japanese homes in the medieval period but might include floor cushions (zabuton), portable armrests, a low table (chabudai), small storage cabinets (kodana), hidden cupboards (shoji), and chests (tansu). These items were often made of unusual wood or bamboo and might be made more elaborate in design and decor using lacquer and gilding. Valuables such as a sword or jewellery were kept in chests, sometimes, according to the ancient Ainu tradition (Japan's indigenous population), in the north-east corner of the house where the guardian spirit of the house, Chiseikoro Kamui, was thought to dwell.

Clothes were usually kept on stands or racks while bedding consisted of either a particularly thick tatami mat (or a pile of thin ones) or a futon, a thin mattress stuffed with cotton, wool or straw which could be easily folded up and kept in a cupboard or corner when not in use. For colder months, a wool or cotton quilt cover was used, a kakebuton. In summer, sleepers might use a mosquito net suspended from the ceiling, a device which has been used since antiquity in Japan.

Decoration

Many people hung artworks inside their homes, and these could take several forms. Hanging scrolls (kakemono or kakejiku) were made from either silk or paper and had a wooden pole at the bottom which served to weigh down the scroll flat against the wall and aid in rolling it up for storage. Scrolls, often hung in a purpose-built alcove (tokonoma) in the wall, showed either a painting or an example of fine calligraphy or a combination of both. In the case of paintings, these typically showed landscape scenes and were usually changed at the beginning of each of the four seasons so that they thematically matched the period in which they were viewed.

Another way to show off one's artistic taste was to have paintings done on the paper sliding doors of the room, on the paper walls themselves or on free-standing screens. A cheaper way to decorate one's home was to buy woodblock prints. These were especially popular in towns and cities from the 17th century CE and typically showed urban scenes (especially related to leisure activities), famous scenic spots, and actors. Prints were pasted directly on to walls or screens. Finally, purely decorative ornaments were used sparingly in the home, but a fine example of porcelain or lacquerware might be displayed. Ornaments and sometimes an arrangement of flowers or an incense burner were placed on shelves which were typically a staggered pair (chigaidana).

Although there might be some valuable collector pieces in a Japanese house, they were not locked in any way, and a burglar need do no more than slide open a window screen or even the front door. For this reason, those who could afford to often employed a caretaker if they were absent for any length of time. Another consequence of this lack of security was that any unknown person approaching a house was treated with suspicion, hence the precaution of visitors calling out 'Excuse me' as they approached the door, a tradition which still continues today in modern Japan.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.