Letters and their delivery via a state communication system was a feature of many ancient cultures. The writing medium may have differed but the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Incas all had the means to send messengers and communications over great distances and do so relatively quickly. Staging posts were established where couriers could eat, rest, change transport or pass on their messages in relays. Although there was no private post system in the ancient world, many individuals did make use of the state communication apparatus or used friends, slaves, merchants, and travellers to send their personal letters over great distances. Surviving letters such as clay tablets and papyrus scrolls contain a mine of information and they have been invaluable to historians interested in such diverse topics as commodity prices, marriage customs, and regional demographics. It is also possible to assess the ancients' attitude to letters through their handbooks on good writing and the publication of collections of letters written by famous names.

Letters in the Near East

Cuneiform letters in the ancient Near East typically took the form of unbaked and baked clay tablets and these were used by scribes to record administrative information and as correspondence between rulers - both to subordinate regional governors and foreign counterparts. The scope of letters eventually widened to include all manner of subjects from history to curses and the material also changed with papyrus scrolls becoming the preferred medium. The latter were usually written in Aramaic. A letter typically had the sender and receiver's names at the top, with the most senior appearing first. It was also stated that the letter was to be read out to the recipient (covering the eventuality that they could not read). Then there followed a passage of formulaic greetings standard to most letters and then the main body of the text. In the case of letters which concerned affairs of state, copies were kept in the royal archives of palaces.

For tablets and scrolls that needed to be sent to a particular destination, couriers were employed. The job, when done for the state, involved a great responsibility as the courier was made liable for the letter arriving where it should. Fortunately for a hard-pressed courier who had to travel a long way, the state provided a network of stopover places to rest and change their mount. Correspondence between private individuals did occur but was at the expense of those concerned, and they could not utilise the state postal system.

The most celebrated postal system in the Near East was the Persian angareion which had stopover points for couriers (pirradazis) located a day's ride apart. The network was paid for and maintained by the local communities it passed through, supplying the couriers with their rations and mounts provided they showed their official sealed document of passage. The system was praised by Herodotus in his Histories (Bk. 8.98) for its resilient couriers who would travel in relays at high speed whatever the weather. Indeed, a quote by the 5th-century BCE Greek historian has been commandeered by the central post office of New York. Inside the post office, a sign reads:

Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointment rounds.

Letters in Ancient Egypt

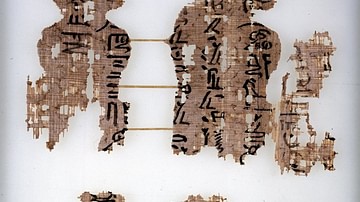

As in the Near East, Egyptian letters were written on clay tablets and papyrus. Some of these letters were also carved onto stone stela and they were written in several languages, notably Akkadian. Egyptian correspondence, at least from rulers, is often peculiarly vague and rather overloaded with formulaic expressions and flattering words only for the benefit of the recipient. One interesting feature of Egyptian correspondence is the use of model letters for the less confident or more inexperienced scribe to copy from. As in the Near East, officials were keen to keep a copy of important letters to cover themselves in case of loss, this was especially the case at Egyptian temples and fortresses.

In the New Kingdom, royal letters were delivered using a system of couriers who generally used horse-drawn chariots to get about the kingdom as quickly as possible. As in the Near East, they were provided with regular stations to change horses and refresh themselves although some would also have travelled by boat down the Nile and its tributaries. A second post network handled the state's administrative correspondence and that functioned as a hierarchy with couriers delivering letters up and down the various levels of local government. We can imagine that private individuals did occasionally send each other letters but these had no dedicated means to arrive at their destination (although one wonders if royal couriers here and elsewhere indulged in a little moonlighting). The best option, then, was to either use a slave or pass on letters to trusted travellers who happened to be going in the right direction.

Letters in the Greek World

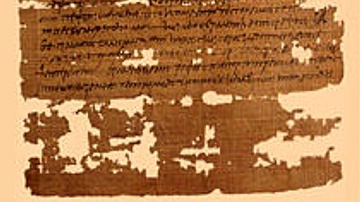

The earliest reference to a letter in the Greek world is in Homer's Iliad, written sometime in the 8th century BCE where Proetus sends a folded tablet to be carried by Bellerophon. Next, Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, describes a series of correspondence between King Amasis of Samos and the tyrant Polycrates, c. 522 BCE. The oldest physical example of a Greek letter is a trio of thin lead tablets which date to c. 500 BCE. Other materials used included pieces of pottery and limestone, animal skins, and tablets covered in a mix of beeswax and carbon, and wooden tablets with a darkened or lightened surface. As in Egypt, though, the preferred form of writing messages was on papyrus. Rather than scrolls, the Greeks typically folded their papyrus documents into sheets, tied them up with string and then put a seal on them to make sure only the intended recipient read them. Pens were often made of reeds and dipped in ink, but writing on wax or clay tablets used a stylus. There was no post network as such in Classical Greece, but there were specialised messengers (hemerodromoi) and messenger ships.

One of the most interesting sources of information on Greek letters is those sent by Hellenistic kings (many of which were copied into stone stelae). They are especially useful for their coverage of royal administrations and how Greek institutions and practices were encouraged across the Mediterranean in the states formed after the collapse of Alexander the Great's empire from 323 BCE. The Hellenistic kingdoms did create a postal network which was staffed and maintained by the wealthy as a form of tax.

Letters in the Roman World

The Romans - both men and women of all ages - continued to use papyrus for their letters but sometimes used parchment (vellum) and tanned leather, too. Papyrus letters were tied and sealed, although the latter could merely take the form of a few ink lines drawn over the top of the string and paper. From the 3rd century BCE, there is a marked increase in personal letters, although correspondents still had to find their own means of sending them such as friends, slaves, and trusted travellers like merchants. The emperors and officials of the state, on the other hand, could make use of the state postal system, the cursus publicus. Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) is credited by Suetonius (c. 69 - 130/140 CE) with creating the Roman postal system (perhaps more accurately described as a communications system) so that he could better govern his vast empire. The system first used couriers (iuvenes) who went all the way from sender to receiver and then, later, relays of them. The messengers were offered rations and fresh transport (vehicula) at regular stations along the 120,000 kilometres (75,000 miles) of road network, which allowed messages to travel some 80 kilometres (50 miles) a day.

There were two types of station - those with accommodation (mansiones) and those designed simply as a place to swap transport (mutationes). Records from a station inscription at Pisidia in southern Turkey, which dates to the 1st century CE, note the precise number of donkeys, mules, and carts a courier was entitled to, provided they carried an official warrant (diploma). Eventually, the cursus publicus was split into two branches, distinguished by whether the couriers travelled by cart (cursus clavularis) or horse (cursus velox). Roman law codes have revealed that the state postal system did experience problems like abuse by private persons, difficulties in acquiring animals and illegally selling postal warrants. It was all operated on a basis of requisition and labour tax so that the postal system became one of the most unpopular interferences of the state in local communities.

Roman letters were very rarely dated, and they typically begin with some stock phrases of greetings and wishing the good health of the recipient. The closing salutations could also be quite long. It still remained common to dictate letters, but the sender might sometimes personally add a few lines at the end. Perhaps curiously to our modern view of writing, it was still rare for letters to express any personal details, thoughts, and opinions, with most correspondence being limited to facts and events. There were, though, a few books created which were collections of letters by famous people, notably Cicero (106-43 BCE), Pliny the Younger (c. 61 - c. 112 CE) and Emperor Julian (r. 361-363 CE). The Romans, seemingly keen to do just about everything well, also wrote handbooks with sample letters and academic commentaries on how to write good letters (typically when considering the skill of rhetoric), an example being the work of Julius Victor in the 4th century CE. We know, too, from references in letters that the Romans had teachers of letter writing.

Letter writing really took off in the early Christian era with literacy rates now around 30% amongst Roman adult males compared to around 10% in Classical Greece and only 1% in the ancient Near East (Oleson, 734). The historian J. Ebbeller describes the period 200 to 600 CE as antiquity's "golden age of letter writing" (Barchiesi, 468) as the Roman elite embraced the sentiment of Cicero's comment in one of his own letters: "what could be more pleasing to me than to write to you or to read your letters when I am unable to speak with you in person" (Letter to His Friends, 12.30.1, quoted in ibid). There also developed the convention that people should reply to letters they had received and there are several surviving examples of Romans complaining that this did not happen - which could well have been down to the risks of travel and lost letters rather than neglect.

Letters in the Byzantine Empire

Perhaps, too, people were inspired by the letters of Saint Paul and others, and in the Eastern Roman Empire, what became known as the Byzantine Empire, certain letters were revered to such an extent that they were read out before audiences. Such was the importance of the state postal system that one of the three highest ministers in Constantinople was put in charge of it, the Postal Logothete (Logothetes tou dromou). By the 4th century CE, more and more care was being put into letter writing and many more handbooks were being produced to guide people. For the Byzantines, a good letter should now include three elements: brevity (syntomia), clarity (sapheneia) and grace (charis). There also grew a fashion for adding little extras to beautify the letter such as adding finely written quotations, proverbs, and riddles to the margins. Finally, the Byzantines were keen to make the best impression possible and so often sent a gift along with their letter, for example, fruit, clothing or a precious stone. The letter and gift were delivered by dedicated letter carriers known as grammatophoroi.

The Chinese & Incas

An overview of ancient letters and postal systems can hardly cover all civilizations but should, at least, include a nod to two other cultures outside the Mediterranean which developed sophisticated and rapid communication networks of their own: the Chinese and the Incas.

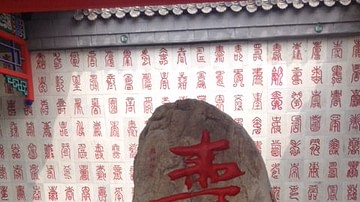

The Chinese were using ink and paper to write from at least the 2nd century CE, and their communications network, already in existence to some degree during the Warring States Period (5th - 3rd century BCE), really took off during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE). Governing a vast empire required fast and reliable communication and the Han messengers were said to be capable of transferring an imperial message at a speed of 480 km (300 miles) in 24 hours, although less than half that seems to have been the norm. Travelling on road or by river, messengers could benefit from over 1600 staging posts by the time of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE).

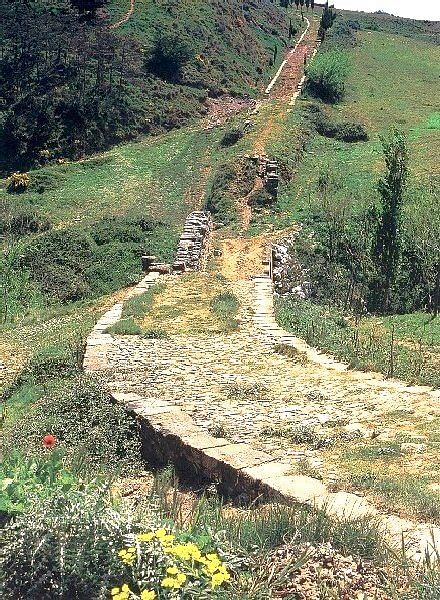

In South America, the Incas (c. 1400-1533 CE) might not have had any letters to deliver - without writing their records took the form of complex knotted strings, the quipu - but they did have a marvellous courier system. The runners (chaski or chasquis) operated in relays, passing information orally to a fresh runner stationed every 6-9 kilometres. In this way, messages could travel up to 240 km (150 miles) in a single day along a network that totalled an impressive 40,000 km (25,000 miles) of purpose-built roads. Clearly, the ancients pretty much everywhere then were just as concerned as we are today with sending and receiving messages as quickly and reliably as possible, and they built up impressive communication networks that, if our technology suddenly failed, we would find difficult to match today.