Authority in ancient Rome was complex, and as one can expect from Rome, full of tradition, myth, and awareness of their own storied history. Perhaps the ultimate authority was imperium, the power to command the Roman army. Potestas was legal power belonging to the various roles of political offices. There was also auctoritas, a kind of intangible social authority tied to reputation and status. In the everyday Roman household, the absolute authority was the father, known as the paterfamilias. In this article, we will examine these various types of authority which spanned across centuries and covered all facets of Roman life - from the household to public politics to the battlefield.

Auctoritas

The Latin term auctoritas is vital to understanding the politics and the social structure of ancient Rome. Read a biography of Cicero (l. 106-43 BCE), Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) or Augustus (l. 63 BCE - 14 CE), and you will be certain to come across the word, auctoritas. However, the term cannot simply be translated to "authority". The best viable translation would be "social authority, reputation, and status". It was different than legal authority, which was translated as potestas. It was also different than military authority, which was called imperium. Rather, auctoritas was an intangible prestige; it was partly earned and partly inherent. It could be earned by valor and braveness in the battlefield, perhaps as a commander, declared imperator or "victorious commander" by his soldiers after a series of victories. It could also be earned by obtaining the most prestigious political magistracies, such as consul, the highest office of ancient Rome. But it was also inherited because one had to have a noble bloodline, ancient family name, and far-reaching social and political connections.

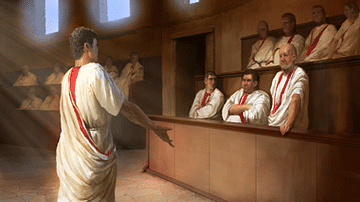

A member of the Roman Senate seeking higher office and prestige usually would have to possess auctoritas in order to get far. Even in court, the auctoritas of the defendant played a major factor. Having deep social connections and auctoritas meant that someone important would defend you on their behalf in court, increasing your chances of being acquitted. For example, both Cicero and Augustus harnessed their social authority and reputation to successfully defend their friends and associates in court, whether it was out of genuine friendship or as a favor to build a political alliance.

The historian Adrian Goldsworthy tells an interesting tale of Pompey (l. 106-48 BCE) in 62 BCE, after having carried out an extremely successful military campaign, defeating Mithridates VI of Pontus (l. 135-63 BCE). Pompey, before he entered the city of Rome, in an effort to dispel the fears of the Roman people who were terrified that he would become a tyrant with his command over so many legions, laid down his command and demobilized the troops. Pompey was sure that even though he "no longer held formal power or controlled an army" he could "rely on that intangible thing the Romans called auctoritas" (Goldsworthy, Augustus, 45).

For even more context, Cicero once dismissively spoke of a very young and inexperienced Octavian as having "plenty of confidence, but too little auctoritas" (Goldsworthy, Augustus, 104). Contrast that with an older Octavian upon entering Rome, after having defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the Battle of Actium. At that point, Octavian was the adopted son of Julius Caesar, consul that year, commander of multiple legions, declared imperator by his soldiers, and thanks to his connection to posthumously deified Julius Caesar, could now trace his ancestry back to the goddess Venus, the demigod Aeneas, and Romulus and Remus. At that point, it was undeniable that Octavian's auctoritas was sky-high.

While on the subject of adoption, another type of authority was that of the paterfamilias (father of the household), the supreme authority within every Roman home. Roman tradition gave the father absolute power over everyone within his home, even the power of life and death if he saw fit. Although it was not often enforced in the later period of the Roman Republic, it was nevertheless a power the paterfamilias could wield. The role of the father was absolute. They were responsible for raising the next generation that would go on to run for office and become the next great men of Rome. From a young age, "boys began to spend more time with their fathers, accompanying them about the business… Boys saw their fathers meet and greet other senators… They began to learn who had the most influence in the Senate and why. From an early age, they saw the great affairs of the Republic being conducted…" (Goldsworthy, Caesar, 38).

The role of the paterfamilias was so important that one of the greatest honors a magistrate - usually a consul or emperor - could receive was Pater Patriae, meaning "Father of the Country". The title originally belonged to Romulus for founding Rome, therefore being the parent of Rome. Cicero received the honor in 63 BCE when he crushed the conspirators in the Catiline Conspiracy. It was also conferred to Augustus in 2 BCE by the Senate for restoring peace and stability to Rome. Later on, future emperors would also receive the honor, such as Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) and Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE).

Imperium

Imperium compared to auctoritas is more straightforward and tangible, however it is not without its peculiarities. Imperium is the authority held by magistrates and promagistrates to command the Roman army. It can be viewed as the supreme form of legal power, which was given to magistrates such as consuls, praetors, and proconsuls. There were essentially two types of imperium: formal and delegated.

To better give a sense of the weight behind the word, let us examine the prophetic appearance of the word imperium in Virgil's Aeneid, written at the time of Augustus. Jupiter, the equivalent of Zeus in Roman religion, gives a prophecy that foretells the birth of the mighty Roman Empire. Virgil (70-19 BCE) writes:

Then Romulus, proud in the tawny hide

Of the wolf who nursed him, will continue

The lineage, build the walls of Mars,

And call the people, after his own name,

Romans. For these I set no limits

In time or space, and have given to them

Eternal empire, world without end. (Latin: imperium sine fine)

(Virgil, translation: Stanley Lombardo, The Aeneid, 10)

This was imperium in a greater sense than mere military authority. Jupiter granted Rome the right to empire, power, and control without end over the world. It is with this context that we can properly view the term. For the Romans, the right to imperium over the world was a god-given right.

Consuls formally held imperium as part of their legal executive authority. Holding the highest political office, the consul possessed imperium over the greatest portion of legions and was in charge of the areas that were of the utmost importance. For instance, if the most pressing matter during a consul's term was a hostile northern tribe raiding and looting Italian cities, then the consul would be the commander of the army and would deal with the matter at hand. Usually, this would culminate in the defeat and ultimately the 'pacification' of the hostile tribe.

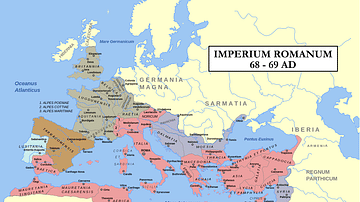

Imperium could also be delegated. Promagistrates, such as a proconsul, were chosen and were delegated imperium by the elected magistrates of that year, using the Senate as an advisory council in their decision-making. The proconsul was usually an ex-consul and acted on behalf of the current consul and was a provincial governor. They would govern the Roman province they were assigned for the duration of their term, during which they had near-total autonomy and imperium over their legions. Since travel times between a province like Hispania (modern-day Spain) and Rome were so great, a proconsul was not expected to send a messenger back to Rome to ask for permission for military decisions. That was unrealistic and not feasible, so they acted as the ultimate authority in their province. Look at Julius Caesar during his time as proconsul; he conquered Gaul in a successful eight-year-long military campaign in which he had total control and responsibility for his legions.

One peculiarity about imperium was where one could hold it. Surprisingly enough, the one place it could not be held was within Rome itself. The formal boundaries of Rome (called the pomerium) were sacrosanct and therefore all army commanders, no matter how successful and no matter how much auctoritas, had to lay down their imperium just outside the borders of the city before entering. This was problematic for some corrupt commanders who fearing retaliation and legal consequences for their unscrupulous actions as proconsul would be completely vulnerable upon entering Rome because they no longer controlled a massive army. Crossing the formal boundaries of Rome with one's imperium and legions was illegal, a dangerous provocation, and sometimes a declaration of war.

Imperium during the time of Augustus and the Principate (Empire rather than Republic) would only change slightly in concept, but greatly in actual practice. In concept, the title and the prestige of a consul or proconsul remained, but in practice, their total military authority was no more; they were subordinate to the Roman emperor in every way. One of the powers that Augustus had as emperor was "maius imperium proconsular… proconsular power that was superior to all other proconsuls" (Goldsworthy, Augustus, 497). Another change during the Principate was that Augustus was granted the right to hold this supreme proconsular imperium even within the sacrosanct formal boundaries of Rome. This gave Augustus military command over every single province in the empire, no matter where he was residing at the time.

Potestas

While auctoritas was tied to many different aspects and imperium was a formidable and sometimes dangerous authority, potestas was the legal authority of a political office. Out of the various types of authority in ancient Rome, this was perhaps the most straightforward because it was defined in the law itself. To narrow our scope, we will examine the potestas of three of the most important Roman political offices: consul, praetor, and tribune.

Being the highest political office, the potestas of the consul was vast; they could propose laws, preside over the Senate, and have military command over the legions. Two consuls were elected every year by the Popular Assembly (Comitia Cenuriata). Each consul had to be at least 42 years old, served a single-year term, and could not serve consecutive terms. By mere virtue of attaining the consulship, he had elevated status and reputation (auctoritas) by reaching the most prestigious and sought-after magistracy, far-reaching legal power (potestas), and military authority (imperium) over the majority of the Roman legions in the areas that were in dire need of military intervention.

During the Republic, the praetor urbanus was second only to the consuls. They were elected right after the consuls by the same Popular Assembly. Praetors were usually given a court to preside over. The trials were performed on elevated platforms in the Forum for the public to witness. The legal power of the praetors was second to the consuls, they too were given imperium over legions and would carry out military campaigns of lesser importance. Furthermore, if a situation arose requiring military action when the consuls were away fighting another war, then the praetor would be called upon to rise to the occasion.

Next was the tribune of the plebs; this role was only available to plebeians. A tribune's person was sacrosanct. It was a crime to physically harm the tribune in any way. A tribune could veto the act of any magistrate and present laws to the Popular Assembly. Upon further examination, the potestas of the tribune of the plebs (tribunicia potestas) was immense, so much so that in the year 23 BCE, when Augustus resigned from the consulship, he sought out and obtained the potestas of a tribune in order to ensure that his legal power remained supreme and uncontested. In other words, even the emperor himself required the potestas of a tribune.

Conclusion

Often, the types of authority were intertwined such as a military and legal authority. For example, in the case of the chief magistrates – consuls and praetors - the command over the legions (imperium) was the ultimate embodiment of their legal power (potestas). The intangible auctoritas helped one climb the political ladder and cement political alliances to reach positions where they could obtain imperium and potestas. Each type of authority played a key role within the city of Rome itself and across its imperial provinces. Commanders exercised their imperium and gained new territory for an expanding empire, the legislative and administrative potestas of the various magistrates in the Roman government was necessary for Rome to flourish, and the auctoritas of an individual could influence important decisions and shape political life.

These roles largely remained stable for hundreds of years during the Roman Republic. From the imperium of Scipio Africanus (236 - 183 BCE) in 3rd century BCE when he defeated Hannibal (247-183 BCE) in the Second Punic War to the revolutionary legislative land reforms of the tribunes, Tiberius (169/164 - 133 BCE) and Gaius Gracchus (160/153 - 121 BCE), in the 2nd century BCE, to the immense reputation of Cicero whose auctoritas gave him incredible authority and influence in the Senate in the 1st century BCE. These roles would only be thrown off balance during the turmoil of the Late Republic - a time of triumvirates, dictators, and civil wars. The role of military authority would also change in Imperial Rome, beginning with Augustus in 27 BCE, during which imperium would no longer truly belong to consuls, praetors, and proconsular commanders but would belong solely to the emperor (princeps). Throughout the centuries, the various types of authority were the engine that powered the social and political structure of ancient Rome.