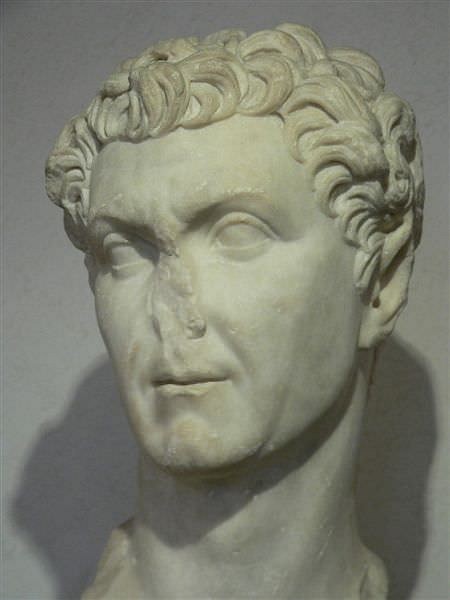

Lucius Cornelius Sulla (l. 138 - 78 BCE) enacted his constitutional reforms (81 BCE) as dictator to strengthen the Roman Senate's power. Sulla was born in a very turbulent era of Rome's history, which has often been described as the beginning of the fall of the Roman Republic. The political climate was marked by civil discord and rampant political violence where voting in the Assembly was sometimes settled by armed gangs. There were two primary opposing factions in Roman politics: the Optimates who emphasized the leadership and prominent role of the Senate, and the Populares who generally advocated for the rights of the people.

During this era, senatorial power was curbed and significant progress was made for the rights of the common folk, particularly the magistracy of tribune of the plebs, which was specifically created to be a guardian of the people. Sulla was an Optimate and after his rise to power, he declared himself dictator and passed several reforms to the constitution to revitalize and restore senatorial power to what it once was. Although his reforms did not last very long, his legacy greatly influenced Roman politics in the final years of the Republic until it fell in 27 BCE.

Sulla & the Late Roman Republic

Sulla was born into an ancient patrician family and so could trace his ancestry back to the original senators appointed by Romulus, the founder of Rome. Part of the cursus honorum, the unspoken but accepted career ladder of public office, was to first serve as a military officer before being able to run for public office. Sulla, by way of his patrician rank, skipped military service and was elected to the junior magistracy of quaestor in 108 BCE. He quickly made a name for himself as an excellent commander and negotiator serving under consul Gaius Marius (l. 157 - 86 BCE) - a Populare who served an extraordinary five consecutive consulships from 104 - 100 BCE - in the Jugurthine War (112 - 106 BCE). A disagreement between Marius and Sulla over who was truly responsible for Jugurtha's capture was the first seed of hatred between the two which would lead to Rome's first major civil war.

Sulla was elected praetor urbanus in 97 BCE and was governor of the province of Cilicia in Asia Minor the following year. The Senate ordered Sulla to reinstate King Ariobarzanes - a friend of Rome - back on the Cappadocian throne because he had been ousted by King Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 120-63 BCE) who wanted to insert his son as the Cappadocian king. Sulla proved successful and was even hailed by his soldiers as imperator, or victorious commander.

In the Late Republic, Italians had long desired Roman citizenship and equal say in politics and power. The Romans had a knack for teasing the Italians with citizenship but never going the full distance in actually passing a law granting the Italians what they wanted. This civil discord reached a critical point in 91 BCE, the start of the Social War, between Rome and Italians who were eventually granted citizenship in 89 BCE after massive casualties on both sides. During the Social War, Sulla had independent command over legions in Southern Italy where he laid siege to the Italian city of Pompeii and successfully fended off armies attempting to aid Pompeii. He fought valiantly and his soldiers awarded him with the Grass Crown (corona graminea), the highest military honor. This military success made him immensely popular back in Rome and won him the consulship of 88 BCE.

Marius vs. Sulla

During his consulship, he was given eastern command of the legions to face King Mithridates VI of Pontus, one of Rome's most formidable enemies, who was wreaking havoc in the east. Mithridates VI had amassed an empire and surrounded himself with allies, and during Sulla's consulship, he ordered all cities in his Asian territories to murder all Romans and Italians. Not even women and children were spared. But before Sulla could embark on his trip to the east and defeat Mithridates VI, Marius and his ally, Sulpicius, using armed gangs and 600 equestrians as a bodyguard had 'convinced' the Assembly to remove Sulla's eastern command and had it transferred it to Marius. Marius then deployed two military tribunes to assume command of Sulla's army.

In one of the crucial turning points in Rome's history, Sulla then gave not a military speech to his soldiers, but a political one, in which he roused his 35,000 legionaries and riled them up about the wrongs done to him and them. The east was known for its endless riches and Marius was now robbing them of the bountiful eastern plunder that would have been theirs. Sulla's stirring speech was successful, and his legions were now loyal to Sulla alone. When Marius' tribunes finally arrived, Sulla's soldiers murdered them. They then commenced their march on Rome to take back what was rightfully theirs. When asked why he would march soldiers against his own country, he replied, “to deliver her from tyrants”. Sulla, the first person to conquer Rome, then overturned Marius and Sulpicius' actions and reinstated himself as consul. Sulla and his legions had the coveted eastern command once again and Marius was forced to flee Rome.

While Sulla was in the East, his strategy was to remove Mithridates VI's control over Greece so he laid siege to Athens in the winter of 87-86 BCE. It was during this time he heard the news that Marius and his faction had returned and captured Rome, passing a decree which declared Sulla an enemy of the state. Marius then cut off money from Sulla's campaign, so he was forced to tax the local Greeks to fund his campaign. Suddenly, back in Rome, Marius died from pneumonia in 86 BCE. Sulla continued his business in the east, finally capturing Athens, successfully winning the Battle of Chaeronea (86 BCE) and the Battle of Orchomenus (85 BCE), convincingly ousting Mithridates' presence, and reinstating Roman authority in Greece. He then spent his time settling and organizing the province of Asia until he finally returned to Italy in 83 BCE to confront Marius' faction in Rome's first civil war.

Sulla and his veteran legions swept through Italy, persuading enemy legions to defect to his side and defeating in battle those who did not. He demonstrated great clemency in forgiving people and cities who decided to change sides. However, once he arrived victorious in Rome, he shed the merciful persona and proscribed (proscriptio) his enemies. The proscriptions were tablets with the names of people who were to be killed for bounty and their land confiscated. In the end, about a hundred senators and over a thousand equestrians perished.

Now that Sulla was wholly unopposed, the remaining Senate annulled the decree which made him an enemy of the state and ordered a statue of Sulla to be put up in front of the Forum Romanum. In order to legitimize his authority, Sulla then suggested that they revive the ancient office of dictator. It had been 120 years since Rome last had a dictator. The Senate, devoid of opposition, was forced to comply with his suggestion, appointing him as dictator to create laws and settle the constitution. Dictators were only appointed in times of great emergency when there was no other option but to entrust all authority and power to one person to save Rome. In the past, a dictator's term was for six months and their powers were essentially limitless. They had power over life and death and could declare war and peace, appoint and remove senators, as well as the power to found and demolish cities. Sulla, however, had no time limit imposed on his dictatorship and therefore could take as long as he needed to settle the constitution.

Reforms to the Constitution

Sulla, now dictator, appeared before the Senate with the powers of a king. 24 fasces were held in front of him as dictator, the same amount that was held before the ancient kings. As perhaps Sulla's most important reform as dictator, he severely diminished the power and prestige of the tribunes of the plebs. Tribunes were originally created to be guardians of the people. Their legal power (potestas) was vast, and because of the progress and precedents made by Populare tribunes, such as Tiberius Gracchus in 131 BCE, when he bypassed the Senate and presented his land reform laws directly to the Assembly, their power grew even stronger.

Sulla sought to undo these advancements, so he required that a tribune must seek permission from the Senate before introducing a law. Furthermore, he got rid of the tribune's all-important veto power. Sulla also stripped the office of its lure and prestige. He decreed that anyone who held the magistracy of tribune should never hold any other magistracy afterward. Understandably, the position was shunned by anyone who wanted to make a name for themselves in politics. The once-great office of tribune with its storied background as protector of the people was now just a shadow of what it once was.

Sulla also formalized the cursus honorum. He forbade anyone to hold the magistracy of praetor until after he had first been a quaestor or to be elected consul before he had been a praetor. He also prohibited any man from holding the same magistracy consecutively. Instead, he would have to wait ten years until he could hold the same office again. Furthermore, he decreed that two years must pass in between magistracies. He also expanded the number of quaestors to twenty and praetors to eight. This growing number of magistrates were needed to govern and administrate an ever-expanding empire.

Another Sullan reform saw that provincial governors would not overstay their welcome in their provinces, greatly reducing their chance to build a personal army to lead against political rivals or Rome itself, as Sulla had done. Because there were a greater number of magistrates under Sulla's reforms, this led to governors not needing to stay in their province long because there were now ample magistrates to fill a vacancy in a province after his one-year term ended. Furthermore, if a governor were to abuse or exceed his powers, they would be tried in the Treason Court (maiestas).

Because the Senate had been significantly thinned out by war, not to mention by Sulla's own proscriptions, he doubled the roll of the Senate from 300 to 600. The Senate had whittled down to a couple of hundred members after his proscriptions, so there were 400 empty spots to fill. As dictator, Sulla himself appointed many of the new Senators from a group of equestrians that he deemed worthy to be promoted to the rank of senator. For the remaining spots, he took recommendations from different people and created a large group of grateful senators thankful for their promotion in rank. The Senate was gaining power as well as strength in numbers.

In one of his most important reforms, Sulla reinstated senatorial power into the courts. Court juries were wielded as an extremely powerful tool at the time. A Populare wanted the jury to be made up of equestrians and an Optimate wanted a jury of senators. If a jury was filled with senators, then as one could expect, they rarely found their senatorial colleagues guilty, but a jury comprised of equestrians would lose very little sleep over convicting a senator accused of corruption. Populares and Optimates constantly fought each other on this. Sulla's reform reversed the tribune Gaius Gracchus' reform to the Extortion Court when he barred senators from being jurors. Sulla then set up seven new permanent courts for murder, counterfeiting and forgery, electoral fraud, embezzlement, treason, personal injury, and provincial extortion.

Sulla cast a long shadow over the Republic in these years. The Senate was very much his creation, purged of all his opponents who had failed to defect to him in time, and packed with his partisans. As a body he had strengthened the Senate's position, restoring the senatorial monopoly over juries in the courts and severely limiting the power of the tribunate. Other legislation, for instance a law restricting the behavior of provincial governors, was intended to prevent any other general from following the dictator's own example and turning the legions against the State. (Goldsworthy, Caesar, 92)

In addition to his reforms, Sulla used his powers as dictator to enact vengeance not just in Rome, but across the Italian regions that opposed him. Among the forms of punishment were massacre, exile, and confiscation for those who obeyed his enemies during the civil war. Their crime could be as little as housing his enemy, lending them money, or doing them any kind of kindness. When charges against individuals were not successful, Sulla took revenge on entire towns. He punished some by destroying their citadels or tearing down their walls, or by imposing fines and suffocating them with heavy taxes and tributes. Sulla set up his troops in colonies in the land and houses of the cities that he took revenge on.

Legacy

Once he settled the constitution, he laid down the dictatorship. The following year in 80 BCE he was elected consul. In 79 BCE he retired from Roman politics altogether and went to live in his country house in Campania where he could try to finish writing his memoirs. According to Plutarch, Sulla foresaw his death in a dream and he stopped writing his memoirs two days before he died in 78 BCE.

Although Sulla's constitution was obediently followed by other Optimates such as Pompey (l. 106 - 48 BCE) and Crassus (l. 115/112 - 53 BCE) - Sulla's reforms would ultimately not endure. He sought to remedy the problems that plagued the Republic, but his solution to the problem was one-sided and only strengthened senatorial power while severely curbing the power of the tribune of the plebs and non-senatorial ranks.

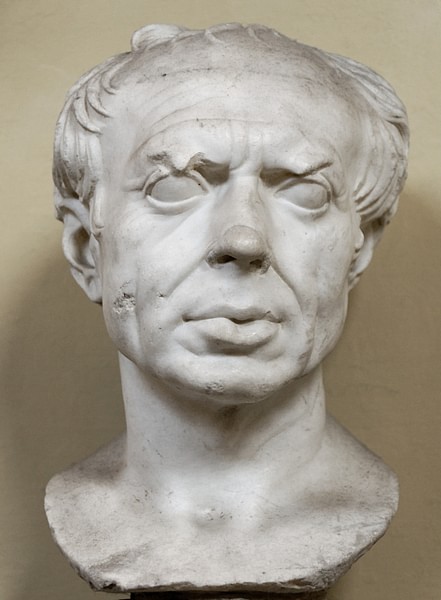

Julius Caesar (l. 100 - 44 BCE) during his time as military tribune spoke out in favor of restoring the powers of tribune which Sulla had thoroughly dismantled. In 75 BCE, Caesar had his uncle, Caius Aurelius Cotta who was consul that year, to pass a bill that allowed former tribunes to seek other magistracies. This was a very important undoing of one of Sulla's key reforms because now the tribunate was no longer a dead-end magistracy, paving the way for ambitious politicians to seek the office once again.

Caesar also reformed and improved another Sullan reform. He had long held interest in the administration of the provinces and his most renowned court appearances were prosecutions of corrupt and oppressive governors. His reforms on the role and behavior of Roman provincial governors would be the standard for centuries to come. Cicero later described Caesar's reform as an “excellent law”. Lastly, Sulla's law of permitting only senators on juries was overturned when praetor Lucius Aurelius Cotta allowed juries to be comprised of both senators and equestrians, leveling the power balance.