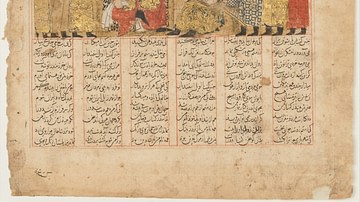

Persian literature derives from a long oral tradition of poetic storytelling. The first recorded example of this tradition is the Behistun Inscription of Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE), carved on a cliff-face c. 522 BCE during the period of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE).

Whatever other works were committed to writing during this era were lost when the empire fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE but the oral tradition continued and would find its greatest expression in the Persian poets of the Middle Ages (476-1500 CE) and, especially, the ten considered the most influential:

- Rudaki

- Daqiqi

- Ferdowsi

- Sanai

- Attar

- Rumi

- Saadi

- Nizami

- Omar Khayyam

- Hafez Shiraz

These poets created the written literature of their culture by combining their traditions, myths, and religious beliefs with those of the Muslim Arabs who had conquered the region in 651 CE and imposed the new religion of Islam on the people. In time, the two cultures entwined, and the poetry of the Persians would come to express the highest concepts of Islamic belief – especially the mystical aspects – completely, even when the works were not written in Persian or even by Persians. These ten poets not only influenced the development of so-called Muslim literature but would affect the literary arts of cultures around the world and continue to inspire readers in the present day.

Religion, Fate, & Love in Persian Poetry

In 651 CE, the Sassanian Empire – which began the process of committing the oral tradition to writing - fell to the invading Muslim Arabs who destroyed many literary works as part of their efforts in subjugating the people. By the time of the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE), however, Persian culture, language, customs, and literature had not only become accepted among the Muslim Arab elite but were encouraged. Under the Samanid Dynasty (819-999 CE), which ruled by the grace of the Abbasids, Persian art, science, and literature flourished and lay the foundation for the future of Persian literary arts.

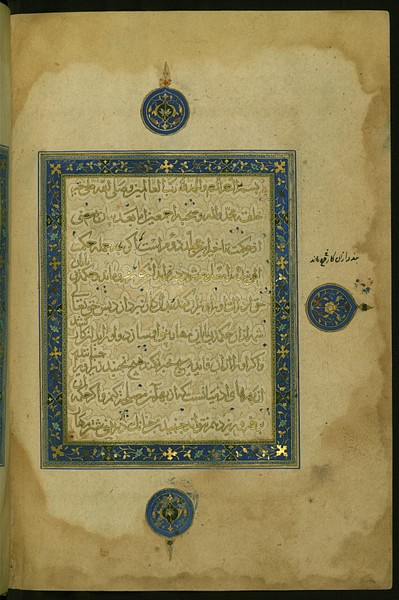

There is no divorcing the work of these poets from their religion of Islam, although some modern-day translators and commentators have tried to do so, as their faith informs their work. Allusions to the hadiths (commentaries) and the Quran run through almost all of these poets' works and even when they are absent (as in Ferdowsi) the poet's faith in a higher good and an ultimate meaning to life informs the piece.

Even so, the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism is an equally potent influence in the work of these artists and, especially, the so-called “heresy” of Zorvanism which claimed that Time was the Father of Existence and encouraged a belief in fatalism. Since time moved an individual through life and toward death, there was nothing one could do to alter one's fate. Juxtaposed against this concept, in all of the following poets' works, is faith in the power of love which transcends time and gives meaning to one's life. This love could be for another human being or directed toward the Divine but, without it, life was considered meaningless.

Poetic diction, the use of symbolism, metaphor, and simile are freely used in all forms of Persian literature from medical treatises to histories but formal poetry was considered the height of expression and, although there were many other great poets contributing to the tradition, the following ten are considered the greatest.

Rudaki (l. 859-c. 940 CE)

Abu 'Abdollah Ja'far ibn Muhammad Rudaki, better known by his penname Rudaki, was the court poet of the Samanid Amir Nasr II (r. 914-943 CE) who so greatly valued him that he made him wealthy. The scholar Sassan Tabatabai notes how, “at the height of his glory, [Rudaki] was said to have possessed two hundred slaves and needed one hundred camels just to carry his luggage” (2). Although he is often cited as first arriving at the court under Nasr II, his surviving work makes clear that he was already a respected poet under Nasr II's father, the Amir Ahmad Samani (r. 907-914 CE). This high level of respect was due to Rudaki's immense talent and skill in mastering every poetic form. Little of his work has survived (only 52 works out of the over one million referenced by later writers) but these make clear he was a poet of immense power who was able to express complex emotional states in simple imagery. He is considered by many the “father of Persian literature” as he created the concept of the diwan (a collection of the short works of a poet) and developed the literary forms of poetry, including the ghazal, qasidas, and rubais.

Daqiqi (l. c. 935-977 CE)

Abu Mansur Daqiqi was equally successful as the court poet of the Amir Mansur I (r. 961-976 CE). Any working poet at this time relied on the patronage of a wealthy admirer, just as in later ages, but a court poet could expect far more than a reliable income as long as he pleased the monarch. The poet would write verses immortalizing the monarch's name and deeds and be rewarded with lavish gifts, and so it was for Daqiqi. At this time, there was an increased interest in Persian history and lore and so Mansur I commissioned an ambitious work on Persian history, lore, and legend from the beginning of time to the present. Daqiqi began the work, drawing on an older manuscript, the Khodaynamag (also given as Khwaday-Namag “The Book of Lords”) from the period of the Sassanian Empire. He had completed 1000 verses of what would have been the Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”) when he was murdered by one of his slaves. As with Rudaki, little of his work survives but extant verse shows he wrote in a highly formal style consistent with epic works. He is best known for beginning the work which would make Abolqasem Ferdowsi's name live forever.

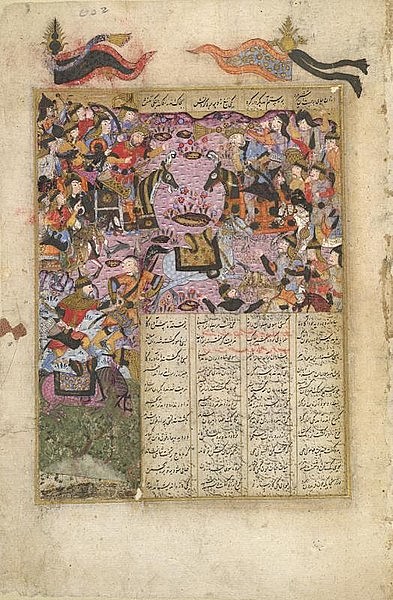

Ferdowsi (l. c. 940-1020 CE)

Abul-Qasem Ferdowsi Tusi was a member of the dehqan, the upper-class landowning members of society comparable to feudal lords in Europe. Almost nothing is known of his life other than that he was obviously well-educated, was married, and had a daughter (though an elegy inserted in the Shahnameh is to a son who predeceased him). After Daqiqi was murdered, Ferdowsi took up the challenge of writing the Shahnameh for Amir Mansur (allegedly to provide his daughter with a dowry) in 977 CE but the Samanid Dynasty fell shortly afterwards and was replaced by the Ghaznavid Dynasty (977-1186 CE) which did not have the same level of appreciation for Persian literature as the Samanids had. Even so, Ferdowsi was encouraged to continue the work which he completed in 1010 CE. How well the Shahnameh was received and whether Ferdowsi was justly rewarded for his efforts by the Ghaznavids is a matter of debate as the accounts concerning this are largely legendary. However the work may have originally been received, it has enjoyed enduring popularity since. Whatever else Ferdowsi may have composed has been lost but the epic Shahnameh, recounting the history, legends, and lore of ancient Persia from the beginning of the world to the Muslim conquest, has long been considered one of the great masterpieces of world literature and is the national epic of Iran in the present day.

Sanai (l. 1080 - c. 1131 CE)

Hakim Abul-Majd Majdud ibn Adam Sanai Ghaznavi was the court poet of the Ghaznavid sultan Bahram-shah (r. 1117-1157 CE) who admired the poet's work so highly that he arranged for Sanai to marry his daughter. Sanai, at this time, had already written a number of pieces praising the Sultan when Bahram-shah decided to make war on India and summoned Sanai to come with him. On his way to the court, Sanai passed a garden in which a drunken man, talking to himself, was loudly criticizing Bahram-shah's foolishness in pursuing conquest for no reason and wasting so many lives. The man also lamented the life of Sanai, referring to him as a talented poet wasting his gifts in praise of a vain and senseless monarch. Sanai instantly understood the truth in what the man said, resigned his position at court, and became a student to a Sufi master. The mysticism of Sufism informs all of Sanai's extant work, notably his masterpiece The Walled Garden of Truth which has been called a “mystical epic” in its exploration of the individual's relationship with God. Later writers (notably Attar and Rumi) were significantly influenced by Sanai who insisted that “error begins with duality” and one must recognize no distance between the self and God. There is no reason to “search for God” because God dwells in the self. One must, therefore, strive to know one's self in order to know the Divine. This concept, as well as his use of wine as a symbol of the intoxicating nature of God's love, would be developed by many of the poets who followed him.

Attar (l. 1145 - c.1220 CE)

Abu Hamid bin Abu Bakr Ibrahim was a chemist (pharmacist) who followed in his father's profession and seems to have lived a comfortable life based on references in his work. He wrote primarily under the penname Attar (“the chemist”) seemingly for his own pleasure as there is no evidence he had a patron. He was not known as a poet in his lifetime (though later he was referenced, as Attar of Nishapur, as a poet) and he rejected the efforts of poets who accepted pay for praising monarchs who were not worth their talents. He focused on verse which would bring a reader closer to an understanding of the nature of existence and the nearness of God. Like Sanai, he was a Sunni Muslim who embraced the mysticism of Sufism which informs his work. He is best known for The Conference of the Birds, an allegorical poem in which all the birds of the world arrive at a meeting to decide who will be their king. The hoopoe bird, known for its wisdom, guides them on a journey through seven valleys – losing many along the way – until they reach the lair of the great mystical bird Simorgh where they come to understand that they must govern and lead themselves. His other works deal with similar themes in developing the Sufi understanding of God and the individual's relationship to the Divine. He was killed in c. 1220 when the Mongols invaded his city of Nishapur.

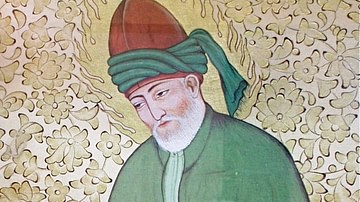

Rumi (l. 1207-1273 CE)

Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi was a polyglot Islamic scholar, theologian, and jurist before meeting the Sufi mystic Shams-i-Tabrizi in 1244 CE and becoming the most famous mystical poet of his time. He was born in Afghanistan or Tajikstan to a literate family, was well-educated, multilingual (writing in his native Persian, Arabic, Greek, and Turkish), and well-traveled. According to legend, when he was 18 years old, he met Attar in Nishapur who gave him one of his books upon recognizing the young man's spirituality. This meeting is said to have laid the foundation for Rumi's later transcendent awakening. He was already a well-respected scholar when he met the Sufi dervish Shams who became his best friend and spiritual mentor. They were only together four years when Shams disappeared one night and was never seen again. Rumi searched for his friend until realizing that the spiritual connection they shared could not be severed by death nor any distance and felt Shams' life force as his own. Afterwards, he began composing poetry which he credited to Shams' spirit. His literary skill and spiritual insight was so vast that he was referred to as Mawlawi (“our master”). His greatest work is the Masnavi, a six-volume poetic exploration of the relationship between the individual and God which references folklore, Sufi spiritualism, the Quran, Muslim legend and lore, and a host of other literary, historical, and religious sources. His shorter works consistently reference the same, weaving folktales and Quranic allusions together with a narrative voice speaking directly to his audience, sometimes clarifying, sometimes obscuring, in order to engage a reader with the subject matter completely. He is regarded as not only one of the greatest Persian poets but among the most influential and widely read in the world.

Saadi (l. 1210 - c. 1291 CE)

Abu-Muhammed Muslih al-Din bin Abdallah Shirazi came from a religious family of the city of Shiraz, Iran and was uprooted at an early age when the Mongols invaded his homeland. His life and philosophy would be significantly affected by this event and the nearly continuous warfare which ravaged the region. He is known as a poet of great depth and skill but can also be considered a travel writer as he spent much of his life moving from place to place (locales and experiences he includes in his work), a historian (as his pieces reference events first-hand), and an existentialist in that he focuses on the importance of living one's life with full awareness of the human condition and one's responsibility to others and one's self. He was well-educated, possibly having a scholarship at the University of Baghdad, before traveling through Syria, Egypt, Arabia, and India. Throughout his travels, he shunned the courts of the elite and academic settings, preferring the company of the common people, especially those who had also been displaced by the Mongol invasion and the conflicts between Christians and Muslims. He returned to Shiraz c. 1257 CE and began to write. He is best known for his poetic work, the Bustan (“The Orchard”), which explores the importance and practice of virtue in one's life and points toward the mysticism of the Sufi dervish in apprehending the Divine.

Nizami (l. c. 1141-1209 CE)

Nizami Ganjavi was born in Ganja (in modern-day Azerbaijan) where he was orphaned at a young age and raised by an uncle who encouraged his education. Nizami's verse attests to his uncle's success in this as he is regarded as one of the most well-read among other highly educated Persian poets. Nizami is known as the leading romantic poet of his age, drawing on the work of Sanai and, especially, Ferdowsi for source material and inspiration. Scholars have speculated that Nizami may have memorized the Shahnameh as Ferdowsi's work informs his own significantly. Nizami continues the tradition of his predecessors in a focus on love – whether between two individuals or the individual and God – as the most important aspect of human existence. Scholar Husayn Ilahi-Ghomshei notes that “Nizami teaches that the only role that man is fit to play in the entire theatre of Existence is that of the lover” (Lewisohn, 78). He is best known for the Khamsa (“Quintet”), a work of five interrelated poems drawing on both Sanai and Ferdowsi, dealing with the subject of human relationships and containing his famous tale of Khosrau and Shirin. Nizami believed that, without love, life was meaningless and an individual life was only worth what it invested in love for others.

Omar Khayyam (l. 1048-1131 CE)

Abu'l Fath Omar ibn Ibrahim al-Khayyam was born in Nishapur to upper-class parents who made sure he was educated by the leading scholars of the day. He is included in this list not because he was considered a great poet but because his poetry – given in English by Edward Fitzgerald (l. 1809-1883 CE) – became popular in the 20th century CE and encouraged Western interest in Persian literature. In his time, he was known as an astrologer and mathematician so exclusively that modern-day scholars have questioned whether the famous Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam is even his original work. Khayyam was best known for contributing to the Jalali Calendar, an innovative solar chart which corrected inaccuracies in the Islamic Calendar. His life, as known by contemporaries and those who wrote shortly after his death, was devoted to science and astrological research. His fame as a poet rests entirely on the efforts of Fitzgerald whose Rubaiyat is not a translation of original Persian poetry but what was known as an “imitation”, a loose rendering of original material, which Fitzgerald himself termed a “transmogrification” (Lewisohn, xiii). Fitzgerald's “translation”, after initially receiving no attention upon publication in 1859 CE, became one of the most popular works of the late 19th and 20th centuries CE and remains one of the most oft-quoted and anthologized literary works in the present day.

Hafez Shiraz (l. 1315-1390 CE)

Khwaja Shams-ud-Din Muhammed Hafez-e Shiraz was born in Shiraz, Iran, presumably to well-educated parents, but little of his life is known outside of references in his works. He is considered the greatest Persian poet, regarded almost as a saint, for the insight and spiritual elevation of his work. He drew on, most likely, all of the above-mentioned poets but most certainly on Sanai, Attar, Rumi, and Nizami in his exploration of love as the central value of human existence. He is said to have known the Quran by heart and embraced the mysticism of Sufism completely as the means of knowing the Beloved – God – whom he felt was the final object of every individual's earthly desire. All one yearned for in one's life was to be rewarded by union with God which one could achieve while living by renouncing what was socially accepted in order to pursue one's own path. He famously seized upon Sanai's symbol of wine as God's elevating effect on the Lover of Truth and rejected the strictures of legalistic religion in favor of individual, mystical, union with the Divine through self-knowledge, self-discipline, and patience with God's seeming silence in the face of sincere supplication. He was recognized as the greatest voice of his generation in his time and a grand tomb was erected over his grave shortly after his death. This tomb was expanded and ornamented in the 1930s CE and today is a site of pilgrimage for the secular as well as religious admirers of the poet's vision.

Conclusion

The works of these poets, and many others, provided the foundation for the continuation of Persian culture and values and allowed for it to flourish and influence the world one recognizes today. The brilliance of these artists in expressing the fundamentals of the human condition and the transforming power of love has resonated across time and continues to encourage faith in a higher purpose and meaning in life.

The literature of any culture is a reflection of the people's communal values, the individual expression of a collective response to being human. The poet expresses what others feel, often without knowing they do, and desire, even if they had no idea of their need until reading the artist's words. All the world's literature resonates with this same value of personal and cultural discovery but Persian literature, in the form of poetry, offers the unique experience of seamlessly blending the world of one's daily life with the transcendence of eternity; not just in one era or through the work of a single artist, but continually from its inception to those who continue the tradition today.