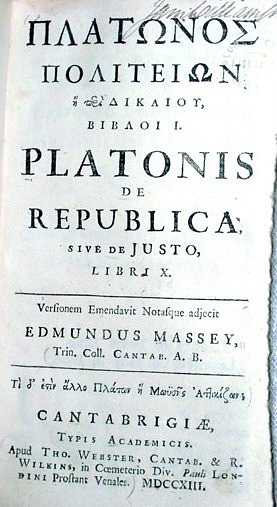

Plato's Lie in the Soul (or the True Lie) is a concept appearing in Republic, Book II, 382a-382d, defined as "being deceived in that which is the truest and highest part of [oneself] or about the truest and highest matters" or, in other words, being wrong or uninformed about the most important aspects of one's life.

In Book II of his Republic, Plato addresses the problem of how one knows that one's beliefs are true. His line of thought raises questions such as, "How do you know whether your most deeply-held beliefs are valid or simply the result of your upbringing, culture, environment, and religion?" Plato attempts to answer such questions by noting a major stumbling block – the True Lie or Lie in the Soul, a falsehood one accepts as truth at a fundamental level, which then distorts one's interpretation of reality, of other people's behaviors and motivations, and of one's own vision of self and truth.

The Lie in the Soul is so dangerous, Plato observes, because, when one has it, one does not know it. The concept can actually be applied to many readers' responses to Republic itself. Plato's Republic is most often read as political philosophy and has been widely criticized for advocating for a fascistic state in which a benign, philosophical, dictator – who supposedly knows what is best for the people – establishes a strict social hierarchy, censors free speech and expression, and restricts the lives of citizens to conform to said dictator's ideal of what is best for the greater good.

This criticism routinely ignores the explicitly stated purpose of the dialogue – to define justice – and the pivotal passage of Book II.369 where Socrates suggests that, in order to understand the principle of justice in an individual, they should consider how justice works on a larger scale:

Maybe more justice would be present in the bigger thing, and it would be easier to understand it clearly, so, if you people want to, we will inquire first what sort of thing it is in cities, and then we will examine it by that means also in each one of the people, examining the likeness of the bigger in the look of the smaller. (Book II.369)

In other words, by defining how the principle of justice works on the large stage of a society, one would be able to then narrow down how it operates in an individual. Republic, then, is not simply a blueprint for an ideal society, but a guideline for how an individual masters the various aspects of one's character to become the best version – the most just version – of oneself. A significant step toward reaching this goal, Plato says, is recognizing the existence of the True Lie or the Lie in the Soul, what it is, and how one may protect or rid oneself of it in order to rationally apprehend truth.

Brief Summary

Republic begins with Socrates, the narrator, attending the Panathenaic Festival in Athens with Glaucon (Plato's older brother) and, afterwards, invited by the philosopher Polemarchus to return home with him. Adeimantus (Plato's other older brother) is with Polemarchus and presses Socrates to accept. Once at the house, Socrates converses with Polemarchus' father Cephalus, leading to a discussion on justice, which is then taken up by others.

This discussion turns, in Book I, to a dialectical duel between Socrates and the sophist Thrasymachus, a guest at the house. Thrasymachus insists that justice is defined simply as the interests of the stronger prevailing over those of the weaker. Socrates refutes this claim by proving that the life of the just person is better than that of the unjust.

Book II continues this discussion with Glaucon and Adeimantus taking up Thrasymachus' claim simply for the sake of clarifying Socrates' argument. It is here that Socrates suggests they lay out the concept of justice as it would work on a grand scale in a city so that, seeing it writ large, they can better manage the concept on an individual level.

Some of the most famous and influential concepts and passages of all of Plato's writing appear in Republic, including the Myth of Gyges, told by Glaucon, which relates the story of a man who finds a ring which will make him invisible and uses it to his own advantage. Glaucon tells the tale to illustrate how people will always use whatever they can to benefit themselves only. Socrates refutes Glaucon's claim by, again, proving that the just and virtuous life is always better than the unjust and self-serving.

Books III-IX develop this argument by steadily constructing the ideal society, ruled by a philosopher-king, and defined by the hierarchy of:

- Guardians – the ruling class who recognize truth and pursue wisdom

- Auxiliaries – defenders of the state who value honor and self-sacrifice for the state

- Producers – those who value material wealth and comfort and labor for the good of the state.

These three classes correspond directly to Plato's conception of the tripartite division of the soul:

- Reason – which seeks truth

- Spirit – which seeks honor

- Appetite – which seeks physical gratification and material goods

The 'state' in Republic – though certainly open to a literal interpretation as a political entity – is figuratively the soul. The individual, Plato suggests, must organize the self in the same way one would structure a social hierarchy. The first step in disciplining the self, however, is making sure one is awake and able to interpret the world and one's place in it correctly.

Plato addresses this concern directly in Book VII through his famous Allegory of the Cave in which prisoners, chained in a cave, interpret shadows on the wall as reality. One prisoner breaks free, leaves the cave, and recognizes the reality of the outside world and the prison in which he and the others have been kept. The choice is then presented to the freed prisoner whether to return to the darkness of the prison and try to liberate others or to simply bask in the light and warmth of the outside world.

Plato strongly suggests that it is the duty of the philosopher, who has seen the truth, to descend back into the cave and help others attain the same level of understanding and break free from their illusions. To free one's self from the lie in the soul, then, one needs to follow the example of the enlightened philosopher.

Republic ends with the story of the warrior Er (also given as Ur) – commonly referred to as The Myth of Ur (which, significantly, Plato himself never designates as myth but presents as reality) in which a soldier dies, journeys to the afterlife, and returns to the mortal plane to tell of his experience. Plato ends the dialogue with Socrates telling Glaucon:

My counsel is that we hold fast ever to the heavenly way and follow after justice and virtue always, considering that the soul is immortal and able to endure every sort of good and every sort of evil. Thus shall we live dear to one another and to the gods, both while remaining here and when, like conquerors in the games who go round to gather gifts, we receive our reward. And it shall be well with us both in this life and in the pilgrimage of a thousand years which we have been describing. (Book X.621)

Plato & Protagoras

A serious obstacle in following after justice and virtue, however, is an inability to understand what concepts like 'justice' and 'virtue' truly mean. In Book II.382a-382d, Plato defines the concept of the True Lie as creating this obstacle without the individual even being aware of it and, through a conversation between Socrates and Adeimantus, defines it further as believing wrongly about the most important things in one's life, thereby impairing one's ability in apprehending the truth of any situation. This concept can be understood as Plato's answer to the sophist Protagoras (l. c. 485-415 BCE) and his famous assertion that "Man is the measure of all things", that if one believes something to be so, it is so.

In Protagoras' view, all values were subject to individual interpretation based on experience. If two people were sitting in a room and one claimed it was too warm while the other claimed it was too cold, both would be correct. Since the perception of reality was necessarily subjective based on one's experience and interpretation of that experience, Protagoras suggested, there was no way a person could objectively know what any alleged truth was.

Plato strongly objected to this view, arguing that there was an objective truth and a realm, high above the mortal plane, which gave absolute value to those concepts humans claimed as true or recognized as false. The essential difference in the view of these two philosophers can be seen in how they might regard the statement, "The Parthenon is beautiful."

To Plato, it would be true to say that the Parthenon is beautiful because that structure participates in the eternal Form of Beauty which exists in a higher realm and is reflected in the physical structure in Athens. To Protagoras, the Parthenon is beautiful only if one believes it to be beautiful; there is no such thing as objective beauty. Plato would – and did – regard Protagoras' view as a dangerous falsehood.

The Lie in the Soul

The Lie in the Soul can be explained this way: if one believes, at a certain point, that eating carrots with every meal is the best thing one could do for one's health and, later, realizes that excess in anything can be a bad thing and stops the carrot-eating, that realization would have no long-term negative consequences on one's life. If, however, one believes the person one loves is a paragon of virtue and then discovers that person is a lying, conniving thief, this discovery could undermine one's confidence in oneself, in one's judgment, in other people, and even in a belief in God, in so far as finding out one is wrong about a person one was so certain of would lead one to question what other important matters in life one might also be wrong about.

Plato, therefore, claims the lie in the soul is the worst spiritual affliction one can suffer from and differentiates this condition from the effects of ordinary lying or storytelling. When one tells a lie, one knows that one is not telling the truth, and when one tells a story one understands that the story is not absolute fact. When one has a Lie in the Soul, however, one is unaware that what they believe to be true is actually false and so they speak untruths constantly without knowing they are doing so.

To believe wrongly about the most important things in one's life renders one incapable of seeing life realistically and so prevents any kind of accurate perception of the truth of any given set of circumstances, of other people's motivations and intentions, and especially, of oneself and one's own personal drives, habits, and behavior.

In the following conversation from Republic, Plato claims:

- No one wants to be wrong about the most important matters in life.

- An everyday lie is not the same thing as having a lie in one's soul.

- Lies in words can be useful in helping friends or in the creation of mythologies which provide comfort and stability to people seeking the answer to where they came from and why they exist.

In order to recognize the lie in one's soul, one must be able to tell truth from falsehood at an objective level, not simply at the level of personal opinion. In order to reach this higher level, one needs to attach oneself to a philosopher and pursue wisdom which leads to discernment. In this pursuit, one will come to understand what one's lie is and, once it is realized, will be able to leave the lie behind and move on to live a life of truth, honesty, and clarity.

The following passage from Republic, Book II, 382a-382d, defines the concept (translation by B. Jowett):

Socrates: Do you not know, I said, that the true lie, if such an expression may be allowed, is hated of gods and men?

Adeimantus: What do you mean?

S: I mean that no one is willingly deceived in that which is the truest and highest part of himself, or about the truest and highest matters; there, above all, he is most afraid of a lie having possession of him.

A: Still, I do not comprehend you.

S: The reason is, I replied, that you attribute some profound meaning to my words; but I am only saying that deception, or being deceived or uninformed about the highest realities in the highest part of themselves, which is the soul, and in that part of them to have and to hold the lie, is what mankind least like;—that, I say, is what they utterly detest.

A: There is nothing more hateful to them.

S: And, as I was just now remarking, this ignorance in the soul of him who is deceived may be called the true lie; for the lie in words is only a kind of imitation and shadowy image of a previous affection of the soul, not pure unadulterated falsehood. Am I not right?

A: Perfectly right.

S: The true lie is hated not only by the gods, but also by men?

A: Yes.

S: Whereas the lie in words is in certain cases useful and not hateful; in dealing with enemies – that would be an instance; or again, when those whom we call our friends in a fit of madness or illusion are going to do some harm, then it is useful and is a sort of medicine or preventative; also in the tales of mythology, of which we were just now speaking – because we do not know the truth about ancient times, we make falsehood as much like truth as we can, and so turn it to account.

A: Very true.

Conclusion

Plato then goes on from this point to elaborate further on the concept which relates back to the argument concerning justice in Republic Book I and informs the rest of the dialogue through Book X. The Lie in the Soul, in fact, could be said to inform all of Plato's work in that he insists on the existence of an ultimate truth which one needs to recognize to live a meaningful life. In attempting to refute Protagoras' subjective view of reality, Plato directly influenced the foundational constructs of the great monotheistic religions of the world – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – and further shaped these systems indirectly through the works of his student Aristotle.

Plato spent his life trying to prove one could find and hold up for the rest of the world to see proof of an ultimate truth apparent to all. From his first dialogue to his last, eloquent and penetrating as they may be, he never found a way to conclusively prove his conviction and for a simple reason: even if one accepts that such a higher truth exists, it must of necessity be interpreted subjectively by each person apprehending it – and it is in that act of interpretation that one risks contracting the Lie in the Soul which distorts that truth. All Plato could finally do was warn people of the danger as he saw it and provide the best advice he could on how to prevent the True Lie from warping one's vision and stunting emotional and spiritual growth.