Women scientists during the Scientific Revolution (1500-1700) were few in number because male-dominated educational institutions, as well as scientific societies and academies, barred women entry, meaning that few had the education or opportunity to pursue a career in science. Some women did overcome these obstacles, and many others, such as male prejudice against their intellectual capabilities and unfounded suspicions over the value and integrity of their research. 17th-century women who made their mark in the fields of astronomy, natural philosophy, and biology include Maria Cunitz, Margaret Cavendish, Maria Sibylla Merian, and Maria Winkelmann.

Obstacles Against Women

Women scientists were the exception in a male-dominated field during the Scientific Revolution. Those few women who did manage to pursue scientific knowledge in their own right had to overcome a great many obstacles. The first barrier to a woman involving herself in science was the lack of education opportunities for girls. In order to study science, a certain level of education was required, and this was not usually open to girls. Not knowing Latin was another crucial block to progress in a field where journals and books were very often published only in that language. This particular obstacle did diminish over time as male scientists began to encourage the use of English, French, and other living languages in the publication of their works and correspondence.

Even if a young woman had gained the benefits of a private education and therefore possessed the intellectual capacity to pursue higher-level studies and specialisations like chemistry, biology, and physics, there was a very definite glass ceiling to further progress. European universities did not permit women students. There were a few exceptions in Italy. Laura Bassi in 1732, for example, was the first woman to receive a degree from the University of Bologna (and she went on to teach physics there).

After the education stage, to then pursue a career in science was nigh on impossible since most scientific institutions – for example, the Royal Society in London – prohibited women from becoming fellows. Such societies and academies were crucial to scientific studies since it was here that funding was provided for research, experiments were conducted, and experimental findings and up-to-date research developments were shared between members. These barriers reflected the predominant male attitude of the early modern period that women could not possess the necessary intellectual skills they thought themselves capable of.

There were a few male intellectuals who championed the cause of women in the field of science. The French philosopher François Poulain de la Barre (1647-1725) called for greater equality in his 1673 book The Equality of the Two Sexes. The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704), who took a keen interest in education, promoted the radical idea that upper-class women should receive the same educational opportunities as their male counterparts. Female authors also pushed for more equality in education and the sciences. Bathusa Makin (c. 1612 to c. 1674) in England and Marie Le Jars de Gournay (1565-1645) in France both published works calling for women to have access to a scientific education. Unfortunately, these voices were but few and so were easily drowned out by the noise of prejudice that still prevailed amongst the majority of males.

Female Scientists in Print

There were a few select areas where women made more impact, and this was scientific knowledge to do with childbirth, the home, and medicine. Midwives were often highly respected for their practical knowledge and experience. For the home, manuals on the efficacy of certain chemicals, chemical mixes, and traditional recipes for the purposes of cleaning were often written by women. Traditional remedies for ailments was another area of publishing more open to women. Again, women often had practical experience here, as part of their expected duties in the household was the treatment of minor ailments suffered by their children and servant staff.

Alchemy was really an early form of chemistry, and one noted female alchemist was Isabella Cortese. Nothing is known of Cortese except that she was an Italian and was daring enough to defy convention in the secret world of the alchemists and write a popular work, The Secrets of Lady Isabella Cortese. The book, first printed in Venice in 1561, contained, besides points of interest to alchemists, many handy recipes such as how to make a good glue, efficient cleaning materials, whitening toothpaste, and health-enhancing cosmetics. The book was very popular and enjoyed eleven editions over the following century. Another successful author was the Frenchwoman Marie Meurdac (c. 1610-1680), who wrote a collection of remedies for ailments and illnesses in 1666, her Benevolent and Easy Chemistry, in Behalf of Women. The book went through several editions, and its original preface made Meurdac's thoughts on women's eligibility to be chemists perfectly clear:

The mind has no sex, and if the minds of women were cultivated like those of men, and if we employed as much time and money in instruction, they could become their equal.

(Moran, 64)

Women were also hidden but important in the fields of translation. For example, Isaac Newton's Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy was first translated into French by Gabrielle Émilie, Marquise du Châtelet (1706-1749). Sometimes, women were the only target audience of periodicals, such as publications like the Ladies' Diary and The Woman's Almanack, which both included articles on science and mathematics. Finally, women were, at least, permitted in the audiences of public readings, scientific lectures, and demonstrations of apparatus provided by male scientists and some academies and societies.

Patrons of Science

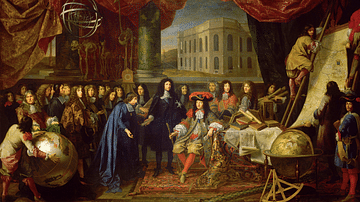

Although males had placed many formidable barriers in the path of women who wished to become scientists, they were happy to accept money from female sponsors. Queen Christina of Sweden (r. 1632-1654) was a noted patron of the sciences in her native Stockholm but also during her exile in Rome, where she funded the Physical-Mathematical Academy. Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia (l. 1618-1680) supported the natural philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650), who, in return, dedicated his Principles of Philosophy to the princess in 1644.

Many upper-class women organised private parties where male scientists and mathematicians were invited along with musicians and artists; this was particularly so in France with the salon system. Such women were not without their critics, illustrating that male opinions had only rarely changed towards equality. For example, salon women were infamously satirised in the comic play The Learned Ladies by the French playwright Molière (1622-1673). Male scientists also came in for satirical treatment, but "women were often attacked more viciously, sometimes drawing on the traditional prejudice that learned women must be unchaste, unattractive, or bad housekeepers and mothers" (Burns, 327).

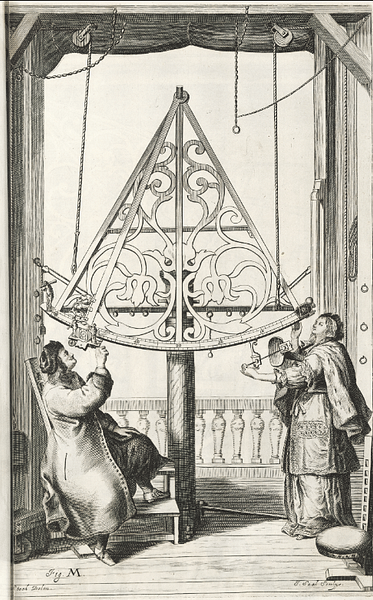

Rather less prominent than the wealthy female patrons, many women were, nevertheless, crucial behind the scenes regarding certain scientific discoveries. These were the wives and daughters of male scientists. For example, Catherina Elisabeth (1647-1693), second wife of the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), was a dedicated assistant to her husband in Danzig (Gdańsk), operating his astronomical instruments and making sure his life's work was published after his death. Astronomers, typically working from a home observatory, seemed to find the assistance of their female relatives indispensable. In another example, Maria Clara Eimmart (1676-1707) helped her father, Georg Christoph Eimmart (1638-1705), in Nuremberg and produced many fine pastel astronomical drawings, including over 250 of the Moon's surface. A rare case of a woman assisting her relation in an official institution is that of Margaret Flamsteed (c. 1670 to 1730). Margaret assisted her husband, John Flamsteed (1646-1719), in his duties at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

Famous Female Scientists

Despite the formidable challenges, some women did manage to become scientists who made important contributions to humanity's knowledge in the early modern period. Below are four such women.

Maria Cunitz

Maria Cunitz (1610-1664) was a German-Polish astronomer who had benefitted from her father's vision in giving his daughter an excellent education in science, medicine, mathematics, and Latin. Cunitz married a fellow astronomer but he was not an intellectual match for Maria. Cunitz's most noted works included Urania Propitia (1650), named after Urania, the Greek muse of astronomy. This work was a simplification of Rudolphine Tables (1627) by Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), which was much needed to make the valuable information therein accessible to a wider number of astronomers. Cunitz's work was impressive, but she still suffered from male prejudice when some male colleagues claimed it was so good that a woman could not possibly have written it. Suspicions were raised that it was her husband who had really written Urania Propitia. To counter these unfounded accusations, Cunitz's husband wrote a preface for future editions declaring this was indeed Maria's original work. Cunitz has not been forgotten and has a crater on the planet Venus named after her.

Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623-1673), was a notable female figure involved in the Scientific Revolution in Britain. Cavendish published extensively on natural philosophy and personally met such famed male thinkers as Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, and Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655). She was also a frequent correspondent with the physicist and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), and she sent the Dutchman a set of her works. Cavendish rejected mechanical philosophy in favour of a world which, although composed of atoms, was intelligent and capable of shaping its own destiny. On the general usefulness of scientific enquiry, Cavendish wrote:

Although Natural Philosophers cannot find out the absolute truth of Nature, or Nature's ground works, or the hidden causes of natural effects; nevertheless they have found out many necessary and profitable Arts and Sciences, to benefit the life of man…Probability is next to truth, and the searching of a hidden cause finds out visible effects.

(Wootton, 569)

Cavendish's book Philosophical Fancies was published in 1653, the first work on natural philosophy in England to be written by a woman. Other noted works include Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1655) and Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy (1666). The latter work included an appendix where she describes a perfect society: The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World. Alas, like Cunitz before her, Cavendish suffered for being a woman in this male-dominated field: "Personally flamboyant and eccentric, with a gift for self-promotion that was viewed as inappropriate for a woman, she was ridiculed as 'Mad Madge'" (Burns, 58). Completely undeterred by what her male peers thought of her, Cavendish used her social rank to attend a meeting of the Royal Society in London in 1667, the first woman to do so and the only one until the miracle was repeated in 1945.

Maria Sibylla Merian

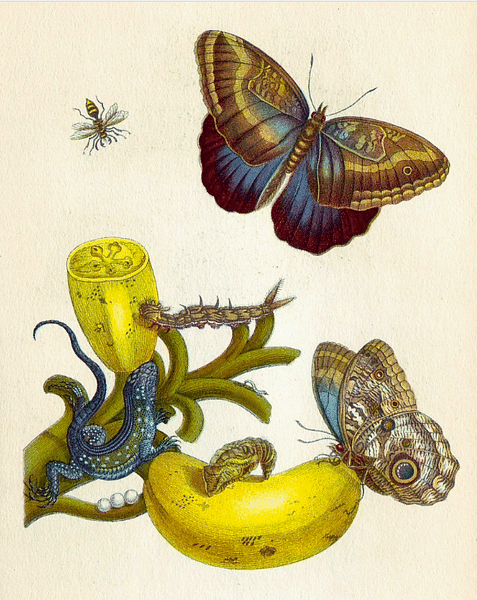

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) made her name in the field of natural history, particularly as an illustrator. Merian certainly had pedigree, coming from a long line of publishers and artists in Frankfurt. Merian moved to Nuremberg and there published, in 1675, her first book, actually a trio of collections of copper-plate engraved illustrations. The books covered flowers and were designed to provide realistic models for other artists and needleworkers to copy from. In 1679, she published another collection of illustrations, Caterpillars, this time showing the various life stages of insects she had observed. The illustrations are often composed to include a great number of insects in the same natural scene. Merian not only drew but also bred and studied the life cycles of many types of insects.

Merian separated from her husband and moved to Amsterdam in 1691 and then went on to Suriname in South America, where she stayed from 1699 to 1701. Suriname was then a Dutch colony and provided the artist with plenty of opportunities to capture, breed, and study exotic insects. The fruit of this work was seen in her 1705 book Metamorphoses of the Insects of Suriname. The book, packed full of expensive coloured illustrations, was a success and introduced to European readers flora and fauna never seen before. Merian was able to fund her work by selling her book privately, selling individual watercolours, and selling insect specimens that she had acquired in Suriname and others sent to her by relatives in various countries. In one letter to a prospective buyer of specimens, she notes that:

I have also brought with me all the animals comprised in this work, dried and well preserved in boxes, so that they can be seen by all. I also currently still have in jars containing liquid one crocodile, many kinds of snakes and other animals, as well as about twenty round boxes of various butterflies, beetles, humming-birds, lantern flies (referred to in the Indies as lute-players because of the sound they make), and other animals which are for sale.

(Jardine, 278)

Merian passed on her enthusiasm for capturing insect life in vibrant prints to her daughters, Dorothea and Joanna, who went on to become excellent illustrators in their own right.

Maria Winkelmann

Maria Margaretha Kirch, née Winkelmann (1670-1720) was a German astronomer. In what seems to have been a common and irresistible attraction of like-minded bodies, Maria learnt about astronomy from her father and then married an astronomer, Gottfried Kirch (1639-1710), who had learnt his astronomical skills from Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687). Maria and Gottfried worked as equals, but typical of the times, it was Gottfried who secured the prestigious post of astronomer at the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1700. Maria continued to work with her husband, and she published three pamphlets on astronomy in her own name. Maria discovered a comet in 1702, although her husband was officially recognised as the discoverer until Gottfried expressly gave her the credit. That Maria was capable of such identifications is made clear by a comment by the celebrated German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716): "She observes with the best observers, she knows how to handle the quadrant and the telescope marvellously" (Jardine, 335).

When her husband died in 1710, Maria's offer of taking up the astronomer position at the Berlin Academy was turned down, not because of a lack of skills on Maria's part but out of fear for the reputation of the academy if a woman were appointed. Maria carried on her astronomy work, particularly calendar-making, by using the observatory of Baron Bernhard Friedrich von Krosigk in Berlin and then that of the late Hevelius in Danzig. Maria's son Christoph continued the family tradition and was appointed the astronomer at the Berlin Academy in 1716.