Christmas carols are a much-loved part of the Christmas season and while many have a long history, others are surprisingly recent. From medieval dancing songs to the 19th-century revival, the words and music of carols have evolved over time as each generation of carol singers continues to add to a mixed tradition of folk music and sacred song.

Origins of Carols

The word 'carol' tends to be exclusively associated with sacred songs related to Christmas, but it once had a wider meaning and referred to several different genres of music used in medieval church services across Europe. The original form alternated burdens (repeated refrains) with stanzas. The strong melody and repeated burdens meant that the carols were easier to remember. Sometimes the burden was in Latin and the verses in the vernacular. The burden was usually sung by a chorus of singers while the stanzas were reserved for a soloist. Christmas church services in the 13th century included the performance of a similar type of song, the simpler conductus, performed in Latin, and early carols were probably used in the same way to describe stories from the Bible. Over time, the carol genre became particularly associated with the celebration of Christmas. Carols were designed to teach the Christian faith and offer a lively method of devotion. They spread across borders, carried by wandering monks and determined pilgrims, and so they became "part of the lingua franca of Christendom" (Poston, 12). As the famed musicologist E. Poston noted: "the essential genius of the carol is its communicativeness" (16).

The exact history and use of carols are not entirely clear, as here noted by the historian and musicologist D. Arnold: "the precise manner of performance, as with most early song forms, is a matter of some conjecture…originally the carol may have been a dancing song (the word probably derives from French carole, a dance where participants formed a large circle), certainly it was frequently sung in procession" (318). An alternative origin of the word 'carol' is from the Latin choraula, which was a type of choral song. An example of a medieval carol that has survived into modernity is Good Christian Men Rejoice (aka In Dulci Jubilo).

Carols were not restricted to church services as there are references to them being sung at festivities such as Twelfth Night (5 January) when singing was seen as a way to ensure good health and a good harvest in the coming year. This activity was known as wassailing and could, from the 16th century, involve singing around a particular fruit tree and passing around a communal bowl of ale or cider. This tradition of pairing music with food and drink is still continued in some places such as at Queen's College, Oxford, where a carol is sung, The Boar's Head Carol, when the medieval dish of that name is carried to the Christmas table. The opening lines are an appetising: "The boar's head in hand bear I/Bedecked with bays and rosemary/And I pray you, my masters, be merry" (Poston, 113).

In France, folk tunes were often used for carols which were called noëls (sometimes spelt nowells on English carol sheet music). These songs were sometimes published in collections such as La fleur des noëls, published in Lyon in 1535. Similar genres existed elsewhere, such as the laude in Italy and the Weihnachtslieder and Christliche Wiegenlieder in German-speaking countries.

In the 17th century, carols were still being written but went into decline as church services did in general. This was particularly so in Britain when the Puritans prohibited the celebration of Christmas following the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). Fortunately for carols and the Christmas festivities, the traditions returned following the Stuart Restoration of 1660. Carol services even began to attract the interest of the most accomplished of composers. In 1734, Johann Sebastian Bach composed his Christmas Oratorio (Oratorium tempore Nativitatis Christi) for performance in Leipzig over Christmas, New Year, and Epiphany. The work is composed of six cantatas, which tell the story of the Nativity of Jesus.

There were more challenges to overcome. The noël in France suffered an interruption in public performance due to the excesses of the French Revolution (1789-1799). Challenges from secular music and changes in lifestyle as traditional rural communities gave up their populations to the expanding urban landscape also contributed to the decline of carols through the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century.

Carols in the 19th Century

The carol genre made a strong comeback in the latter stages of the 19th century, largely thanks to the increase in popularity of the Christmas celebration and, rather ironically for such religious music, because the holiday became increasingly secular and commercial. Listening to and singing Christmas carols became their only point of contact with church activities for those who did not attend Christmas Day morning matins. In England, the Victorian era witnessed a surge in interest in Christmas celebrations (some might say the Victorians practically reinvented Christmas). Several verses of popular carols often appeared inside Victorian Christmas cards which became popular from the 1840s.

This revival in all things Christmasy not only meant new carols were written but there was also active research into the seemingly lost carols of the Middle Ages. Antiquarians hunted through private collections and church archives and interviewed rural villagers with long memories. Many old carols, once found again, were given new lyrics, sometimes only in part, sometimes the whole, much to the lament of purist musicologists. The first English book of carols dates back to 1521, a collection compiled by the London printer Wynkyn de Worde. Alas, only fragments survive today of this collection of what are called 'Christmasse Carolles'. It was the Victorians, though, who ensured old carols were not forgotten in their own time and by future generations by collecting them in anthologies. One of the most celebrated collections of carols was Carols Ancient and Modern, compiled by William B. Sandys and Davies Gilbert and published in 1823.

It is curious that many of the most well-known carols today are often not as old as we might think. There are also many carols which come from outside Britain. Once in Royal David's City was a 19th-century addition to the carol repertoire, this one written by Cecil Frances Alexander (1823-1895), the wife of Archbishop Alexander, Primate of All Ireland. Away in a Manger, written by the American writer William James Kirkpatrick (1838-1921), was originally intended for singing in Sunday school; it first appeared in print in 1885. O Little Town of Bethlehem is another carol by an American writer, this time the Bishop of Massachusetts, Phillips Brooks (1835-1893), but this one shows the link between Britain and the United States with its tune being a traditional English folk song called The Ploughboy's Dream (later renamed Forest Green). The Three Kings of Orient, which has a verse for each king, was composed by John Henry Hopkins Jr. (1820-1891); he was also a bishop, this time in Vermont.

Carols were popular at camp meetings in the United States, and amongst slaves on plantations. A popular carol sung on plantations was Rise Up, Shepherd, An' Foller while Children, Go Where I send Thee! is a typical Afro-American spiritual carol.

German-speaking countries have a strong tradition of Christmas carols. Silent Night, Holy Night (Stille Nacht! Heilige Nacht!) was composed in Austria in 1818. It was written by Joseph Mohr (lyrics), the parish priest, and Franz Gruber (melody), the schoolmaster of Hallein for performance at Christmas services because, at least according to legend, the church organ had broken down after a mouse had got into the workings and caused havoc.

Carol Singing

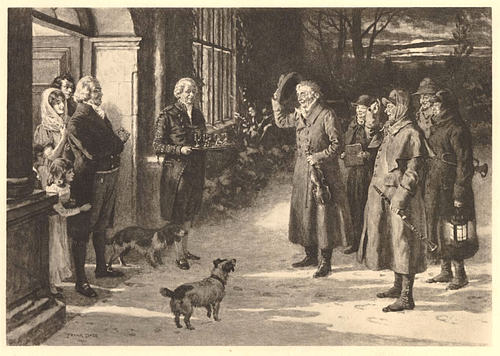

People sang carols at home by the family piano, very often after dinner in the Christmas period. They also sang in taverns, a tradition that remains strong in certain counties of England, especially Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, and Derbyshire. A new, open-air phenomenon arrived in the Victorian era, which was for groups, particularly of children, to sing carols outside people's homes in the hope of receiving food and drink or money (for themselves or for charities). This was not an entirely new activity since in the Middle Ages there had been a tradition for travelling troupes of actors and singers to visit people's homes at this time of year and offer impromptu performances.

Victorian carol singing was traditionally done on 21 December (the feast day of Saint Thomas) and on Christmas Eve. Appreciative households made sure they had warm mince pies or hot punch at the ready. Some people went around singing and offered sheet music of carols or printed lyrics for sale. Street musicians would adapt their repertoire at this time of year, performing carols with their fiddles, pipes, penny whistles, accordions, and organs. Carols were particularly suited to bell ringing, performed by small groups or an individual armed with a string of ten or more bells.

A famous example of this carol-singing tradition in literature appears in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1812-1870), first published in 1843. Here a solitary carol singer has the courage (or folly) to sing at the door of the old miser Ebenezer Scrooge:

The owner of one young nose, gnawed and mumbled by the hungry cold as bones are gnawed by dogs, stooped down at Scrooge's keyhole to regale him with a Christmas carol; but at the first sound of

God Bless you, merry gentleman!

May nothing you dismay!Scrooge seized the ruler with such energy of action that the singer fled in terror, leaving the keyhole to the fog, and even more congenial frost. (Dickens, 14)

Five Popular Carols

The 20th century continued to see an interest in carols, and scholars endeavoured to catalogue the original tunes and arrangements, sometimes returning them to resemble more their medieval appearance and sound. Two notable works in English are The Oxford Book of Carols, first published in 1928, and The Penguin Book of Christmas Carols, published in 1965. Here below, five popular carols are presented with the lyrics quoted taken from the latter work.

God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen

This traditional folk carol tells the story of the Nativity and the visit of the shepherds to Bethlehem. The original version should have a comma after 'merry' in the opening line. Nowadays, the often missing comma gives a false impression that the gentlemen have just rolled out of a tavern after celebrating Christmas. Such errors over time are not uncommon with traditional songs, but this carol suffers from a second one. The line "So frequently to vanquish all/The friends of Satan quite" most likely should be "fiends of Satan".

God rest you merry, Gentlemen

Let nothing you dismay,

For Jesus Christ our Saviour

Was born upon this day,

To save us all from Satan's power

When we were gone astray:(chorus)

O tidings of comfort and joy.In Bethlehem in Jewry

This blessed babe was born,

And laid within a manger

Upon this blessèd morn;

The which his mother Mary

Nothing did take in scorn:From God our heavenly Father

A blessèd angel came,

And unto certain shepherds

brought tidings of the same,

How that in Bethlehem was born

The Son of God by name:'Fear not', then said the angel,

'Let nothing you afright,

This day is born a Saviour

Of virtue, power, and might;

So frequently to vanquish all

The friends of Satan quite:'The shepherds at those tidings

Rejoicèd much in mind,

And left their flocks a-feeding

In tempest, storm and wind,

And went to Bethlehem straightway

This blessèd babe to find:But when to Bethlehem they came,

Whereat this infant lay,

They found him in a manger

Where oxen feed on hay,

His mother Mary kneeling

Unto the Lord did pray:Now to the Lord sing praises,

All you within this place,

And with true love and brotherhood

Each other now embrace;

This holy tide of Christmas

All others doth deface:

(Poston, 73)

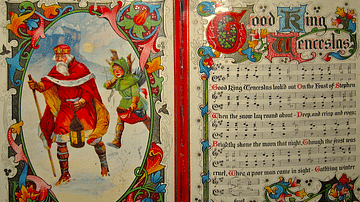

Good King Wenceslas

The carol Good King Wenceslas tells of the Bohemian duke Wenceslaus I (r. 921-935) who gives charity to a poor man and so reminds, as its last line indicates, that those who bless the poor will themselves be blessed. In real life, Duke Wenceslaus (aka Vaclav) was known for his acts of charity and ambitious church-building programme; he was given the honorary title of king by Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 962-973) and made a saint. Wenceslaus is today the patron saint of the Czech Republic.

The tune of this carol is much older than the text and dates to the 13th century when it was used for dancing. Rather ironically, the modern lyrics, written by John Mason Neale (1818-1866) c. 1849, describe deep mid-winter weather and contrast starkly with the original carol, Tempus Adest Floridum (It is Time for Flowering), whose words praised spring.

Good King Wenceslas last looked out,

On the Feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about,

Deep and crisp and even:

Brightly shone the moon that night,

Though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight

Gathering winter fuel.'Hither, page, and stand by me,

If thou know'st it, telling,

Yonder peasant, who is he?

Where and what his dwelling?'

'Sire, he lives a good league hence,

Underneath the mountain,

Right against the forest fence,

By Saint Agnes' fountain.''Bring me flesh, and bring me wine,

Bring me pine-logs hither:

Thou and I will see him dine,

When we hear them thither.'

Page and monarch, forth they went,

Forth they went together;

Through the rude wind's wild lament

And the bitter weather.'Sire, the night is darker now,

And the wind blows stronger;

Fails my heart, I know not how;

I can go no longer,'

'Mark my footsteps, good my page;

Tread thou in them boldly:

Thou shalt find the winter's rage

Freeze thy blood less coldly.'In his master's steps he trod,

Where the snow lay dinted;

Heat was in the very sod

Which the saint had printed.

Therefore, Christian men, be sure,

Wealth or rank possessing,

Ye who now will bless the poor,

Shall yourselves find blessing.

(Poston, 75)

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

This carol was adapted in the 19th century by Dr William H. Cummings (1831-1915) from a chorus titled Festgesang (Festive Song) written in 1840 by the noted German composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847). Mendelssohn thought that the tune better suited a song about soldiers rather than a sacred subject. The lyrics used today were written by Charles Wesley, first published in 1739, and then tweaked by George Whitfield in the 1740s. The carol presents a rousing hymn of praise to Jesus Christ and his role on earth; it is usually performed at the end of Christmas church services.

Hark! the herald angels sing

Glory to the new-born King;

Peace on earth and merry mild,

God and sinners reconciled:

Joyful, all ye nations, rise,

Join the triumph of the skies,

With the angelic host proclaim

Christ is born in Bethlehem:

Hark! the herald angels sing

Glory to the new-born King.Christ, by highest heaven adored,

Christ, the everlasting Lord,

Late in time behold him come,

Offspring of a Virgin's womb;

Veiled in flesh the Godhead see,

Hail the incarnate Deity!

Pleased as man with man to dwell,

Jesus, our Emmanuel:Hail the heaven-born Prince of Peace!

Hail the Son of Righteousness!

Light and life to all he brings,

Risen with healing in his wings;

Mild he lays his glory by,

Born that man no more may die,

Born to raise the sons of earth,

Born to give them second birth:

(Poston, 79)

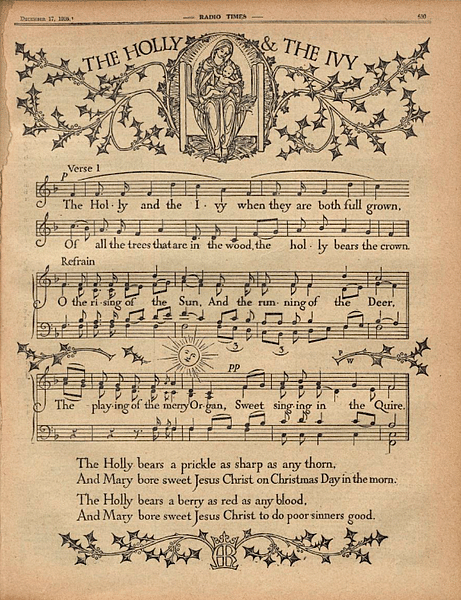

The Holly and the Ivy

The traditional carol The Holly and the Ivy perhaps indicates better than any other the pagan traditions that Christianity sought to assimilate and hide. Holly was the traditional symbol of the male while Ivy represented the female, and both plants, being evergreens in a period when nature seemingly slumbers, were strongly associated with pre-Christian traditions celebrating mid-winter, including the Roman festival of Saturnalia. The lines regarding the rising sun and running deer also remind of pagan rites. The Christian lyrics create a simile between features of the holly plant and the crucifixion. There is another connection in that holly was thought to have sprung up when Jesus carried the cross to Calvary. Holly has long been regarded as a symbol of good luck and used to decorate churches and homes at Christmas time, as it still is today, most visibly on the wreath many people hang on their front doors. The carol dates to the 17th century but gained a new audience when it was catalogued by Cecil J. Sharp in 1913.

The holly and the ivy,

When they are both full grown,

Of all the trees that are in the wood,

The holly bears the crown:(chorus)

The rising of the sun

And the running of the deer,

The playing of the merry organ,

Sweet singing in the choir.The holly bears a blossom

As white as the lily flower,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

To be our sweet Saviour:The holly bears a berry

As red as any blood,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

To do poor sinners good:The holly bears a prickle

As sharp as any thorn,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

On Christmas day in the morn:The holly bears a bark

As bitter as any gall,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

For to redeem us all:The holly and the ivy,

When they are both full grown,

Of all the trees that are in the wood,

The holly bears the crown:

(Poston, 117)

O Come All Ye Faithful (Adeste Fideles)

The lyrics of O Come all Ye Faithful are credited to John Francis Wade (1711-1786) from his composition Hymn on the Prose for Christmas Day. The work first appeared in print around 1782, and as Wade was a Jacobite who wanted to restore the House of Stuart to the English throne, it may be that the lyrics are calling for Jacobites to rise in support of what turned out to be a lost cause.

The bilingual nature of the carol was useful during the First World War (1914-1918) when on Christmas Eve pockets of British and German soldiers all along the front of trenches called an unofficial truce. The men sang carols to each other across no man's land, as here reported in a letter home by Private Oswald Tilley:

First the Germans would sing one of their carols and then we would sing one of ours, until when we started up 'O Come All Ye Faithful' the Germans immediately joined in singing the same hymn to the Latin words 'Adeste Fideles'. And I thought, well, this was really a most extraordinary thing – two nations both singing the same carol in the middle of a war. ..This experience has been the most practical demonstration I have seen of Peace on earth and goodwill towards men…It doesn't seem right to be killing each other at Christmas time.

(Lawson-Jones, 92).

Below are the English lyrics of the carol, but there is a matching Latin version, Adeste fideles.

O come, all ye faithful,

Joyful and triumphant,

O come ye, O come ye to Bethlehem;

Come and behold him,

Born the King of angels:

O come let us adore him,

O come let us adore him,

O come let us adore him, Christ the Lord.God of God,

Light of Light,

Lo, he abhors not the Virgin's womb;

Very God,

Begotten not created:Sing, choirs of angels,

Sing in exultation,

Sing, all ye citizens of heaven above;

Glory to God

In the highest:Yea, Lord, we greet thee,

Born this happy morning,

Jesu, to thee be glory given;

Word of the Father,

Now in flesh appearing:

(Poston, 93)

Carol Services Today

Carols continued to be composed in the 20th century, such as In the Bleak Mid-Winter, composed by Gustav Holst (1874-1934) with lyrics from a poem by Christina Georgina Rossetti, which first appeared in 1906, and Jesus Christ The Apple Tree, composed by Elizabeth Poston in 1967. Carol services remain, of course, a popular feature of the Christmas holidays, but not only on the 25th of December. For example, carol services are still offered today at Westminster Abbey to mark the beginning of Advent (the end of November or the first days of December), the Feast of St. Stephen (26 December), and the Feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December). In the UK, a much-loved televised carol service is that at King's College, Cambridge, performed on Christmas Eve since 1918. Neither is the genre itself stuck in the past as contemporary composers and poets continue to write new carols to challenge the popularity of those evergreen songs that instantly remind us of Christmas.

Popular Christmas Songs

In the 19th-century revival of Christmas singing, carols faced growing competition, at least outside church services, with other traditional but more secular songs, some of which had been around for a few centuries themselves. This repertoire of secular songs includes such classics as We Wish You a Merry Christmas, O, Christmas Tree (aka O Tannenbaum), and Jingle Bells.

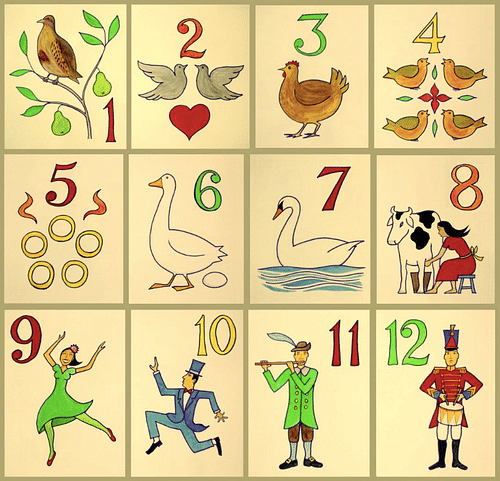

The Twelve Days of Christmas is a traditional forfeit song, that is, it was sung at gatherings as a game where singers had to remember all the lines or suffer some sort of harmless and amusing penalty. The song's title refers to the 12 days of the Christmas period, which run from Christmas Day to 5 January. The song's lyrics, which first appeared in print c. 1780, have changed over the years, singers of the early versions, for example, had to remember lines like "Nine hares a-running", "Ten hounds a-hunting" and "Twelve bulls a-roaring".

The song was popular in England and France before crossing the Atlantic, and this layered history may explain why there remain several versions of the lyrics around today, although the first six lines generally remain the same in all versions. The 'five gold rings' line is sung differently from all the others because it was an addition made in 1906 by the composer Frederick Austin. The French connection may also explain what the partridge is doing up in a pear tree (partridges are ground birds), the rather odd first gift in the opening lines On the first day of Christmas/my true love sent to me/A partridge in a pear tree. The pear tree might actually have been a perdrix (a game bird) that was incorrectly copied or mispronounced until it became established as a 'pear tree'. So, really, the first day's gifts were a more affordable pair of game birds: a partridge and a perdrix.

The Twelve Days of Christmas brings us back to carols since there is a theory that the song's lyrics have a religious significance. The whole song may be a catechism used by Catholics in times of persecution to teach their children the essential elements of the Christian faith. If that is the case, then below is presented the meaning of each of the 12 gifts, a memory game within a memory game:

- A partridge in a pear tree – Jesus Christ

- 2 turtle doves – the Old and New Testaments

- 3 French hens – the 3 virtues of faith, hope, and love (or charity)

- 4 calling birds – the 4 gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John

- 5 gold rings – the first 5 books of the Old Testament, the Torah

- 6 geese a-laying – the 6 days of Creation

- 7 swans a-swimming – the 7 gifts of the Holy Spirit (wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord)

- 8 maids a-milking – the 8 beatitudes (e.g. the merciful, the meek, and the pure of heart)

- 9 ladies dancing – the 9 fruits of the Holy Spirit (e.g. love, joy, and peace)

- 10 lords a-leaping – the 10 commandments

- 11 pipers piping – the 11 faithful Apostles

- 12 drummers drumming – the 12 points of the Apostles Creed (e.g. the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting)

(Lawson Jones, 68)

Such double meanings have been a common feature of songs for centuries, especially those aimed at children. The hidden meaning is difficult to prove or disprove, but it remains an intriguing possibility, and, if anything, it is a reminder that for this song and for many of the other carols mentioned above, we are not always fully aware of the true meaning of the words we know so well and sing so heartily at Christmas time.