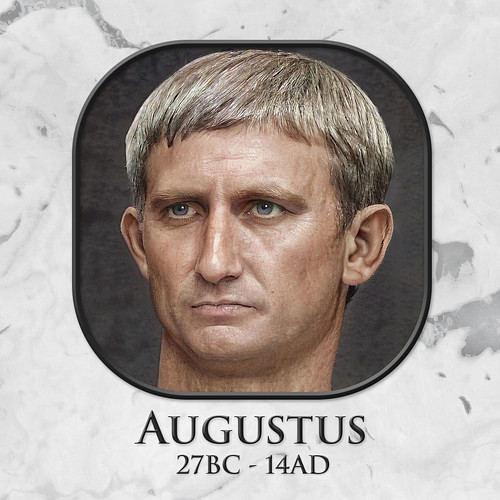

Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), as the adopted son and heir of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), brought an end to the Roman Republic, and on 16 January 27 BCE, by Senatorial decree, he became the first Roman emperor. However, he would not be addressed as a king, but as a princeps, the first citizen.

Principate

A natural politician, Augustus was seen to be both intelligent and communicative as well as tenacious and cunning, and he soon realized he would need to be cunning and wise to avoid his own Ides of March. He had learned from the assassination of Julius Caesar and was smart enough to avoid the mistakes his predecessors had made. After defeating Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Augustus faced another major challenge: he had to stabilize the Roman government, and he had to do so in a manner "that would leave him in charge without exposing himself to the daggers that had brought down Caesar" (Strauss, 25).

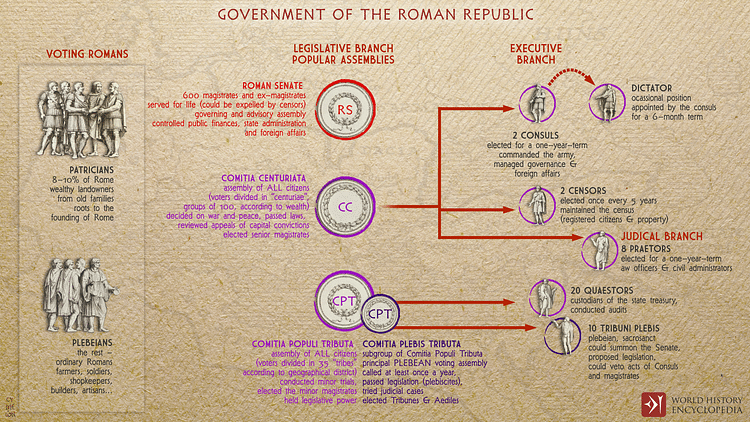

Barry Strauss, in his Ten Caesars, called Augustus Machiavellian. From 42 to 30 BCE, "he fought, lied, cheated and trampled on the laws" (28). Upon becoming emperor, Augustus found a way to adapt the traditional practices of the Roman constitution to new situations but changed their meanings completely. It was considered a 'pragmatic resolution' to the problems of a one-man rule. From 31 to 23 BCE, he retained continuous consulships. He was given, upon his request, the powers of a tribune for life by the Senate, allowing him to not only propose legislation but also exercise the veto. In addition, he was also granted imperium maius, in other words, power superior to any magistrate or proconsul. Besides the legal authority, the emperor also had what the Romans called auctoritas: prestige, respect, and the ability to impress others. Both would be essential to maintain his power.

Suetonius (c. 69 to c. 130/140 CE), in his Twelve Caesars, noted that besides the tribunician powers awarded to Augustus, he was also given the tasks of supervising public morals, scrutinizing the laws, and holding a public census. He added that the emperor had thought about restoring the republic but decided that "to divide the responsibilities of government among several hands would be to jeopardize his own life but also national security, so he did nothing" (58). Strauss claimed that, in theory, Rome remained a republic, but in practice, Augustus was a monarch. He managed changes "not by the language of revolution but by the language of reform and renewal" (32). He spoke in a manner that implied he was restoring the republic, but not in the way many in Rome had hoped.

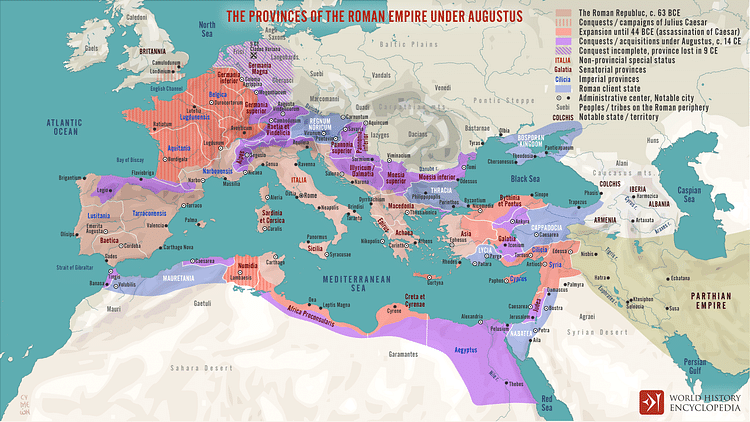

Adrian Goldsworthy, in his Pax Romana, contended that Augustus' constitutional power had developed over time through trial and error as offices, honors, and privileges were given to him. He believed Augustus' reign, known as the Principate, was, in fact, a monarchy. Augustus' power relied on his control of the Roman army, and with this control, he demonstrated his callousness and desire to extend the Roman Empire. His control of the military enabled him to make essential decisions without the consent of the Roman Senate or the assemblies. He justified his arbitrary decisions by not only his loyal service to the Republic but also his victories in foreign wars. Goldsworthy was not alone in his assessment of the emperor. In his article The Emergence of the Monarchy 44 BCE - 96 CE, Greg Rowe wrote that over time the principate "had come to be seen as a monarchy in which the emperor was more than the sum of his delegated powers." (Companion, 114)

However, unlike other monarchies, the Principate preserved the institutions of the old Roman Republic: the Senate, the popular assemblies, the magistrates, and the priesthood. Rowe added that the emperor's working relationship with these institutions seems to have given the Roman Principate its "distinctive character." Rowe believed that after Augustus had achieved sole power "there was no question that he would dissolve the Republic" (ibid); however, he kept his promise to put the Republic in order and maintain a working relationship with it. As with the assemblies, the Senate's authority was greatly reduced – no longer in control of foreign policy, finances, and Roman warfare. Its number was also reduced from 1,000 to only 800.

Transforming Rome

Carlos Gomez, in his Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, said that when Augustus' powers increased so did the greatness of the city: "The creation of a grandiose image of the capital and the growth of the rest of the empire was a fundamental purpose of the Augustan reforms" (36). When Augustus assumed leadership over Rome, he saw a city that had been neglected for decades, falling into disrepair. He began the necessary reforms by first reviewing all state practices and public customs. Before Augustus, the aediles had controlled the city's public works and security, but that was to cease. Several necessary changes were made under the emperor. To increase the water supply to the city, two new aqueducts – Aqua Virgo and Aqua Julia – were built under the supervision of Agrippa. Grain distribution to the poor was made more efficient. Augustus also took measures to protect the city from crime and fire: the vigiles, a fire brigade was created with seven cohorts of freedmen to protect against fire as well as to police the city. To protect the emperor, the Praetorian Guard was created – nine cohorts of 500 each.

He also made efforts to beautify Rome, rebuilding decaying temples and monuments. Aside from three new theaters and an amphitheater, he commissioned the Pantheon built around 27 BCE, restored the Temple of Pompey, the Via Flaminia, and cleaned the banks of the Tiber. Gomez wrote that "transforming the city gave Augustus an opportunity for self-promotion" (55). On the field of Mars, Augustus built his own mausoleum. Southeast of the tomb was the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace or Altar of Augustus) dedicated on 30 January 9 BCE.

Religion, Morals, Arts

Augustus was well aware of the state of religion in Rome and the moral decay of the city – something that had been a complaint of the Roman orator Cicero (106-43 BCE) years earlier. Augustus hoped to solve these issues by encouraging marriage and childbirth and by initiating a number of religious reforms. Among the laws enacted by the emperor was the Lex Julia de adulteriis coercendis, which made adultery a criminal act, and the Lex Papia Poppaea, which penalized unmarried men and childless couples.

Augustus hoped that a restoration of the old customs and religious beliefs would provide a renewed trust in the traditional gods and would help restore the confidence of the people. He built a number of new temples: one to Apollo on the Palatine, one to Jupiter on the Capitoline, and others to Minerva, Juno, and Jupiter on the Aventine. The emperor became a pontifex, an augur, one of the decemviri, and, in 12 BCE, he became pontifex maximus, thereby making all appointments of priests.

He made changes to the festival calendar, adding 30 new pageants, some of which celebrated the events of his life and recent Roman history (his birthday became a state festival). Augustus established a new series of secular games, the Ludi Seculares, complete with animal sacrifices and theatrical performances. The poet Horace (65-8 BCE) wrote a secular hymn, Carmen Seculares, at the request of the emperor. A literary man himself – author of the Res Gestae (a first-person account of his life and accomplishments) – he encouraged others, such as Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and the historian Livy, fostering the golden age of Roman literature.

Pax Romana

One of Augustus' greatest accomplishments was the Pax Romana (Roman Peace): 200 years of relative peace (27 BCE to 180 CE), ending after the 'five good emperors', with the onset of the reign of Commodus (r. 177-192 CE). It was a golden age of stability, economic prosperity, and Roman imperialism. As an indication of this power, he closed the gates of the Temple of Janus, which had been open since the First Punic War. According to Goldsworthy, this peace "came from victory and strength, and privileges so overwhelming that in the future no aggressor would dare risk going to war" (169).

Although Augustus had been awarded supreme military powers, both in Rome and in the provinces, he realized that changes needed to be made to his legions. The capture of Cleopatra's financial resources had made it possible to finance the military. The emperor reduced the number of legions from 60 to 28. This reorganized Roman army was now a standing, professional army, and every Roman legionary was made to swear an oath, not to the state, but to Augustus.

Conclusion

Augustus changed almost everything about Rome, making it, as he claimed, a city of marble. According to Gomez, he considered himself a new Romulus – a founder of a new Rome. To the citizens of Rome, he became pater patriae or father of the country. In the words of Matthew Dennison in his The Twelve Caesars, "the story of Augustus' reign is one of constant political realignment of the transference of power associated with formerly elected offices to an unelected head of state" (48).