Training in oratory was a crucial part of Roman education; it was associated with a young boy's transition into adult life. As Athens was considered the intellectual centre of the eastern Mediterranean, many students undertook long journeys so that they could attend the best-known specialised rhetorical schools or study at one of several established philosophy centres.

Roman Education

Education was seen by the Romans as crucial to self-advancement. For young upper-class boys, it was key to obtaining an important position in ancient Roman society. Girls from the well-to-do and elite circles tended to be married at a very young age and did not formally advance their studies, although they may have received a sophisticated education from private tutors.

Originally, training in oratory was not provided within a school context but carried out under the tutelage of a famous statesman who would prepare his young pupil for a political career in the Roman government. However, by the 2nd century BCE, Greek culture had a significant influence on the Roman Republic, and the traditional approach made way for the Greek education system. In Greece, specialised teaching centres had existed for centuries, and gradually, schools of oratory became established in Rome, too. Ancient philosophy was divided into three areas; ethics, physics, and logic; pupils wishing to study philosophy could attend centres offering studies in Greek on doctrines such as Epicureanism and Stoicism. Alternatively, the young Roman boy could leave home to study abroad.

Some modern scholars have referred to this period in a young person's life as going to 'university'. However, the word is used loosely as there was no official curriculum and no official degrees. Nevertheless, going to 'university' in ancient times did entail not only advancing one's studies but also leaving one's family for a new environment and lifestyle in which a student could become a part of the culture of a famous intellectual centre.

During the Republic, notable figures were amongst those who travelled abroad for educational purposes including Julius Caesar (c. 100-44 BCE), the politician Marcus Junius Brutus (85-42 BCE) the orator Cicero (106-43 BCE), poet and satirist Horace (65-8 BCE), and Marcus Tullius Cicero the Younger, son of the orator. Generations later, we have the writings and correspondences of former students like the Latin rhetorician Aulus Gellius (123-165 CE), the Greek sophist and rhetorician Libanius (314-393 CE), and the Greek sophist, Eunapius (c. 345 to c. 420 CE), who provide valuable insights through their own experiences of studying in Athens.

Preparation & Costs

The young boy preparing for his studies abroad may have been as young as 15 years of age when he faced a journey to Athens of about 12 days, weather permitting. Some young boys would be accompanied by their pedagogue who had the responsibility of taking care of their young master and reporting home on his behaviour and progress to his family. To advance his studies in rhetoric, oratory, declamation, and philosophy, the family of the prospective student sought teachers of high reputation; for some, these included the elite schools such as Plato's Academy and Aristotles' Lyceum or 'Peripatetics' where Aristotle in his time, would have strolled the covered walkway of the Lyceum whilst lecturing his students.

Athens was recognised as the best place to become completely immersed in the ideas of both ancient and contemporary thinkers. One ancient commentator made the observation that there were some young pupils who came to the schools of Athens out of an earnest desire for learning and then there were those who were 'sent'. Cicero, who furthered his own education abroad, 'sent' his son, Marcus Cicero junior, to study at Athens with the famous peripatetic, Cratippis. We are informed from Cicero's own writings that young Marcus was more inclined to enlist as a soldier than further his studies abroad, however, eventually, he agreed to Athens.

It was expensive to live and study abroad. Cicero, in Epistulae ad Atticum (his letters to his banker and friend, Atticus), provides an insight into the finances required to keep his son in Athens; substantial school fees and a very generous allowance to cover apartment, slaves, and living expenses. Studies could last up to five years, and with considerable costs involved, it is understandable that not all Roman students continued their studies. Those who did would have been wealthy, aiming for careers in politics or academia. Nevertheless, two years in Athens was often sufficient for a career, and students of relatively modest means tended to opt out at this stage. Libanius refers to an occasion when a father pulled his son out of his class; he was two years into his course, and Libanius thought this far too early, however, within the following year the young man would triumphantly win a trial as a lawyer.

Arrival & Initiation

The young Roman boy arrived at the busy port of Piraeus in Athens after his 12-day journey. According to Eunapius and Libanius, some of these young pupils were met in the Athenian port by competing groups of students loyal to a particular teacher. These students would abduct the new pupils and recruit them into the school of their professor. Libanius, who wrote of these events based on his own personal experience, speaks of these skirmishes as if they were routine occurrences. Libanius recalls that he was captured by a group of these students and put in a cell no bigger than a barrel until he swore an oath to the students' favoured teacher, Diophantus (Or 1.16.20).

A new student's initiation process is described by Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 330 to c. 389 CE), theologian and former pupil, in his Orations. Those who were charged with the young boy’s honour arranged themselves into two ranks and led him to the baths. When they approached the baths, the older students shouted and leapt wildly as if possessed, calling out that they must not advance as the baths would not admit them; they then furiously knocked at the doors of the bathhouse, frightening the new young pupil, before they finally allowed him to enter. Gregory of Nazianzus, comments on the performance by saying that, for those young boys who have never experienced this, it would have seemed fearful and brutal, but he says, it was very humane and the threats were feigned rather than real. Eunapius (c. 345 to c. 420 CE ) describes the students taking the ritual bath whilst being mocked by their older peers, with the intention of reducing the conceit of the newcomers and bringing them to submission. Initiation complete, the student was welcomed into the school and given a short, coarse cloak to wear. Known as a tribon and associated with philosophers, this cape was to be worn in public and whilst engaged in study.

Studies

Students studied with their teacher in the open air, in a temple or sometimes at the teacher's home. Gymnasia, originally used for athletic activities, were adapted to include areas for intellectual studies during the Hellenistic period. It became common for one or more exedrae – walled recesses – to be constructed in a gymnasium. These exedrae were rectangular or semi-circular rooms, where teachers and their pupils could sit here to hold discussions and give lectures, and libraries were also added. At Athens, the gymnasia became the seats of nearly all great schools of Greek philosophy.

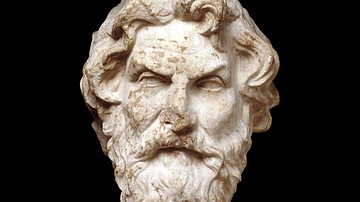

In his Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists, Eunapius gives descriptions of lectures given by some of the noted figures of the time, such as his vivid portrait of the sophist, Prohaeresius (c. 276 to c. 368 CE) who, when giving his lectures, leapt in the air like one inspired; he was tall, strikingly attractive, with ample gestures and sonorous rhetoric. Eunapius describes Prohaeresius' orations as masterpieces of showmanship and overwhelming eloquence.

The Athenian sophist, Philostratus (170-245 CE), writing in his Vitae Sophist also provides a series of sketches of philosopher-sophists in action and an insight into some of the ways of learning available to students. Some students, we are told, paid to listen to lectures (a fee per lecture) from different professors, and in addition to this, they had access to the professors' library to complement the lectures; students who had their own professor might also take advantage of paying to attend various professors' presentations. There was another group of students who would have shared a more intimate pupil-teacher relationship, and these students were given specific instruction in their studies of rhetoric and philosophy; these students were chosen based on their personal merit.

By way of Libanius, who after completing his studies in Athens went on to teach rhetoric, we have further insight into student life. Libanius writes of his classes where time was spent at preparatory exercises (progymnasmata); the students were given a subject and were taught to write eulogies and invectives, and they also presented orations before their peers. In some cases, the best students were allowed to take over from Libanius and teach certain classes. We know from surviving letters that at the finish of a 'term', during the summer break, Libanius wrote informal 'reports' for parents, a method of keeping them updated on their son's progress (Epist. 650).

Student Life in Athens

Student life was not dissimilar to present-day university life. We can imagine hubs of student activity existing around these centres of learning. Many young students were experiencing, for the first time, the freedoms that came with being away from home. In many cases, students remained during the holidays in the towns of the centres of education. We certainly could imagine the many temptations for the student in this new life; games, chariot races, parties and late-night carousing. Aulus Gellius, who studied philosophy and rhetoric at Athens, writes in his Noctes Attica, of a teacher complaining that in Socrates' day, students walked all night to hear Socrates speak, while now the teacher must wait on the students who have spent the entire night drinking and as a result are hungover until midday (7.10.5).

Cicero's son, Marcus, fell to temptation, and his "scandalous behaviour", which included drinking and partying, was reported to his father by the Athenian Leonides (Ad Fam. 16.21.2). Young Marcus was neglecting his studies to the great displeasure of his father, who threatened to stop his allowance if the situation carried on. For students studying such a distance from home, their wayward behaviour was not likely to result in a disgruntled father arriving on their doorstep, although Cicero did consider a visit. His son went about calming the waters with a letter of apology by way of his father's secretary, Tiro; Marcus writes that the errors of his youth have caused him much remorse and suffering, that his heart sinks from what he did and his ears cannot bear to hear mention of it. He professes having reformed his ways and working hard at his classes now. He also manages within this letter to refer to his generous allowance as meagre and request a secretary to save the labour of copying out his lecture notes (16.21).

Gellius' description in his Noctes Attica also refers to those times spent enjoying the new environment and new friends. He tells of Roman and Greek young men who attended the same lectures coming together to look at the sights of Athens and discuss their interests. They practised their new skills together, learning to conduct their own philosophical interactions (15.2). Gellius describes an occasion when the pupils met for dinner and entertained themselves with intellectual games in which answering correctly meant that they received a crown of woven laurel and a prize. Strong bonds and friendships were created over the years as students progressed through their studies.

Final Exam & Career Prospects

The end of a young man's course at 'university' was marked by the final evaluation in which he had to give a rhetorical performance in front of an audience of his peers; Libanius writes that in his school after the test he would comment and evaluate his student's speech. Gregory of Nazianzus recounts, that in some towns, returning students were expected to demonstrate the skills they had mastered to a large public audience. Some students viewed it with trepidation, and Gregory tells how he felt ill with the tension at this crucial moment in his life.

The young boys who had come to Athens to study oratory and rhetoric could now apply their new skills during lawsuits and in careers of diplomacy; many ambassadors were orators or sophists, but philosophers could equally take on these roles. The young graduates could also become teachers and academics.

The student who had arrived as a young pupil at the port of Athens some years before prepares for his leaving. Gregory of Nazianzus gives an emotional account of bidding farewell. He describes how teachers and pupils flocked together at the quayside, tears flowing as farewell speeches were made; nothing, he says, is more painful than saying farewell to Athens and those students with whom one shared both joys and sorrows (Or.43,24).