Although life expectancy was lower in ancient Greece and Rome, many people survived into old age. Those who reached old age tended to accumulate wealth and political power. However, the societies of the ancient Mediterranean were also often hostile to the visibly aged and infirm. The experience of old age in antiquity, and the extent to which the elderly were marginalized by society, depended on their wealth, gender, and social class.

Reaching Old Age in Antiquity

Contrary to popular belief, people in the ancient world did not have extremely short lifespans. Although the average life expectancy in the ancient world was between 20 and 30, this statistic is skewed by very high rates of infant mortality. Almost everyone who survived childhood would live to middle age, and it was not uncommon for people to reach their 60s and 70s. However, before modern medicine, lifespans were still shorter and health concerns were more debilitating. Karen Cokayne estimates that approximately 1.6 % of Romans reached 80 years of age, and only 0.05% reached 90.

in antiquity, there was no strict definition of old age or a formal retirement age. Instead, the transition from middle age to old age varied between individuals, based on their health and social life. In ancient Greece and Rome, the onset of old age was generally considered to begin around the age of 60 for men and around 50 for women. These ages corresponded to the time when people began to have difficulty performing physical labor, and when women typically reached menopause. Men were also excused from mandatory military and civic service after this age. These changes signaled the end of childbearing and the ability to fully participate in agricultural work, meaning that people could shift to a new role in the community, with a different set of social responsibilities.

[Elderly age] brings about the renunciation of manual labour, toil, turmoil, and dangerous activity, and in their place brings decorum, foresight, retirement, together with all-embracing deliberation, admonition, and consolation; now especially he brings men to set store by honour, praise, and independence, accompanied by modesty and dignity.

(Tetrabiblos, 4.8.206)

The Athenian statesman Solon (c. 640 to c. 560 BCE) considered the average lifespan to be 70 years, which could be divided into seven phases of life. The astronomer Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria (c. 100-170 CE), in his astrological treatise, the Tetrabiblos, similarly divided the human lifespan into seven phases of 12 years. The final stages of life were associated with old age, when men stepped away from hard labor and risk-taking, to focus on retirement and wiser decision-making.

Geriatric Care

Greco-Roman physicians understood many of the health concerns associated with old age, including eyesight and hearing problems, arthritis, and an increased susceptibility to respiratory illness. They were also aware of mental challenges in the extremely old, such as memory issues and senility. Ancient physicians believed that these changes were because the humors within the body became unbalanced, creating a deficiency of heat.

But in ensuing time, as all the organs become even drier, not only are their functions performed less well but their vitality becomes more feeble and restricted. And drying more, the creature becomes not only thinner but also wrinkled, and the limbs weak and unsteady in their movements. This condition is called old age.

(Galen, San. Tuenda 5.1.2)

Despite an awareness of age-related illness, the extant works on Greek and Roman medicine do not devote much space to geriatric care or life extension. Roman and Greek medicine often focused on prevention, rather than treatment. Authors like Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BCE), Celsus (c. 25 BCE to 50 CE), and Galen (c. 129-216 CE) recommended various prophylactic medical treatments and dietary changes to help preserve health in old age.

Ancient medical regimens typically involved adequate rest, exercise, and regular bathing throughout life. Galen recommended that old men eat a diet that included less meat and was higher in dried foods, wine, and fruit. Greco-Roman writers also noted the importance of intellectual exercises, like writing and gardening, to preserve mental acuity in old age.

The Role of the Elderly in Ancient Society

As men and women entered old age, their position in Greek and Roman society changed. Most people earned their subsistence through hard physical labor, such as farming and weaving, which became difficult in old age. However, most people did not have the means to retire. These concerns were less important for the upper classes, who relied on income generated by their servants and estates. For the wealthy, old age could be a time of leisure and retirement.

Aristocratic men often continued their careers in law and politics well into old age, benefiting from years of accumulated experience and reputation. In ancient Athenian democracy, other Greek city-states, and the Roman government, many political offices had minimum age requirements, preventing young and irresponsible candidates from holding them. The Spartan Gerousia and Roman Senate both originated as councils of elders.

As age increased, if things followed the expected course or according to a man's or family's aspirations, he could expect to rise up the career ladder, to increase his wealth and to widen his social and economic networks through the marriages of his children.

(Harlow & Laurence, 121)

At the same time, many men experienced ageism as they competed with younger men for political power and social influence. While men in Rome and Athens had the ultimate authority over their household and property, this could be challenged by their adult sons, especially if their mental competence was called into question. The loss of independence and authority that could accompany extreme old age was compared to a second childhood by many Greek and Roman authors.

Greco-Roman Attitudes towards Aging

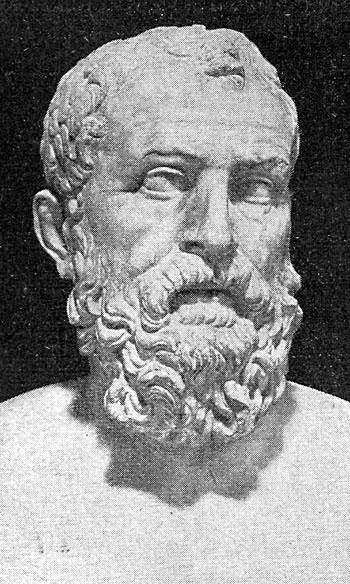

Attitudes towards old age in Greek and Roman literature are extremely polarized between authors who reflect on the ways in which the elderly benefit society, and authors who view old age with scorn. The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) had an extremely negative view of the elderly, believing that the cooling of the humors contributed to a characteristically pessimistic and cowardly character among the old.

Some historians have noted that the surviving Roman and Greek literature was disproportionately produced by older, aristocratic men. This is partly because this demographic was the best educated and had the most free time. A particularly influential treatise on the subject is On Old Age by Cicero (106-43 BCE), who wrote it from the perspective of a fictionalized Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE).

There is a host of literary material on the survival into old age, because the elderly used the otium or leisure time associated with this period of life as time to write. They wrote as consolation for themselves in old age facing death and it is this format that produces much of what we today associate with a stoic philosophy of survival in adversity. That adversity was old age.

(quoted in Harlow & Laurence, 12)

Old age is portrayed ambivalently in Greek and Roman mythology. Geras, the god of old age in Greek mythology, and his Roman counterpart Senectus are fearful figures that no mortal can resist. The myth of Tithonus, a man who was given eternal life by the gods but not eternal youth, also evokes a fear of aging. However, other mythological figures, such as Nestor, are shown to grow in power and knowledge with old age.

Aging & Beauty Standards in Antiquity

Greek and Roman beauty standards placed a high value on youth. As a result, many people attempted to mask signs of aging with cosmetics like make-up, hair dye, or wigs. These types of cosmetics are often satirized or described derisively in Greco-Roman literature. Men and women who attempt to mask their age are frequently portrayed comically, especially when they do so in an attempt to pursue younger spouses or partners.

Greek imagery offered some positive representations of aged philosophers, but the positive representation tends to be overwhelmed by images of old age as loathsome and youth, particularly male youth, as beautiful. (Troyansky, 27)

In Archaic and Classical Greek art, youthful figures are portrayed far more frequently than old ones. When old subjects are portrayed, they are frequently depicted as tutors and sages or, in the case of women, as priestesses and nursemaids. Hellenistic sculpture dealt with a wider variety of subjects than Classical Greek sculpture but still portrayed aged subjects with a degree of contempt.

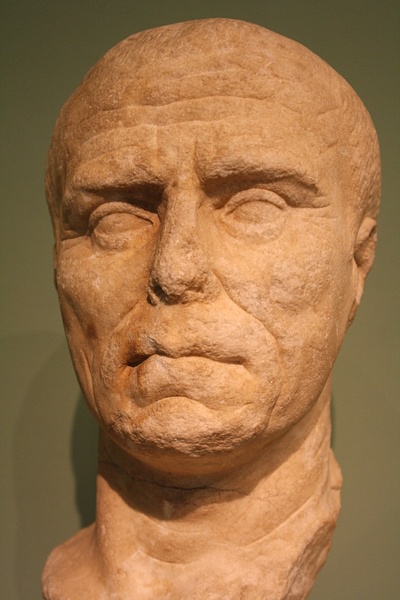

Classical Roman portraiture differs from Greek conventions by portraying realistically aged male and female figures more positively. In Roman art, a mature or severe face conveyed power and experience. In male portraits, features like deep frown lines and receding hair signified their dignity, seriousness and maturity.

Aging & Gender

Greek and Roman literature tends to portray old women more derisively than old men, in keeping with the patriarchal social norms of the Mediterranean. Because the role of women in the Roman world was primarily to be wives and mothers, they were at greater risk of becoming socially marginalized once their sex appeal and reproductive ability had diminished. Women were also believed to age faster than men, which was generally explained through the idea that their bodies and minds were naturally frailer. Despite this, medical writers typically ignored women in their treatises on old age, preferring to focus on age-related ailments that affected men.

[I]n ancient Greece old women constituted a marginal category, which was loathed and feared by men. (Bremmer, 245)

Women in ancient Greece and Rome often lived significantly longer than their husbands, and it was common for women to be widowed in middle age or old age, after which they relied on their children for support. When older widows remarried, this could cause friction between their new husband and their adult children, especially over control of the woman's inheritance.

Despite an overall negative attitude towards elderly women, some older women found themselves in positions of increasing power as they became free from the obligations of marriage and motherhood. Many women exercised political power through their familial and social influence, which they used to help shape the careers of their children and grandchildren. Livia Drusilla (59 BCE to 29 CE) and Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi brothers (c. 190-115 BCE), became famous examples of politically prominent Roman matriarchs.

Support Systems for the Elderly

There were no governmental support systems for the elderly in the ancient world, so kinship networks were often the only source of care for the old. Greek and Roman culture placed a high value on filial piety, the social and moral obligation that children have for their parents. In keeping with these values, adults were expected to care for their parents in old age. An honorable person would provide for their parents' basic needs and provide them with social companionship. Most people lived in multigenerational households, which made it easier for them to support their older relatives. It was extremely shameful for a person to neglect their elderly parents, and in some societies, parents could take legal action against their children or heirs if they were not being adequately looked after.

A competent judge will order you to be supported by your son, if his means are such that he can provide you with food.

(Code of Justinian, 5.25.2)

Parents commonly sought to improve their children's economic prospects by providing them with an education or arranging a beneficial marriage for them. It was also common for parents to bequeath property to their heirs while they were still alive, to help with the cost of their care. Aristocratic families could more easily care for aging and disabled relatives with the help of servants, which improved the quality of life for all members of the family.

A person who had no children or grandchildren could still rely on their spouse for support. Freed slaves also had a responsibility to support their former masters in old age. These overlapping social obligations meant that most people had some form of assistance as they navigated their later life.