A Roman boy's rite of passage, a ceremony or ritual marking a transitional period in life from childhood to adulthood, was the assuming of the toga virilis, the adult toga. The ceremony usually took place sometime between the boy's 14th and 17th birthday; the decision was made by the boy's father or guardian.

The ceremony is referenced widely across historical writings, biographies, letters, and speeches, however, the ancient primary sources available to us do not provide too many details. There is in general a scarcity of ancient material written about children, and we certainly have more information regarding the lives of the middle-class and elite families than we do of the lower classes, and a boy's rite of passage is no exception.

Timing

A boy's rite of passage would have corresponded with puberty, a time defined by some ancients as a period of 'ferocitas', that is, impetuosity or restlessness. The physical transition from a boy to a young man was marked by several features including the 'breaking' of his voice, which was known as 'gallulascere' (crowing), and by the growth of facial hair. At 14, a young boy may have had the first growth of a beard; this first growth was associated with adolescence and visually marked out the young boy from the adult male. This growth was allowed to become a full beard and was not shaved off until the boy was in his late teens to early twenties. When finally the shaving of the beard occurred, it was seen as the end of the wayward youth and a progression into a more adult life. The shaving of the beard could sometimes be carried out at a public festival known as the Iuvenali; at this festival, the young man's beard was dedicated to a god of his own choosing and kept in a small box in the sanctuary of the family's household gods.

A boy in his early teens was still under the supervision of his pedagogue, who would also have accompanied him outside of the home. Roman education for a youth from the affluent or elite society, would have included rhetorics, oratory, law, politics, astronomy, geography, law, literature, philosophy, and mythology. Some boys may have been considering leaving home to advance their education; there were Roman students in Athens and the other intellectual centres of the Eastern Mediterranean. In many cases, they would have been accompanied abroad by their pedagogue.

By the time Roman boys had reached the age of 14, many fathers would have already been taking their sons to observe life in the Roman Forum, they would have attended public meetings and the Roman law courts, and sons would have been introduced to their father's friends and business acquaintances. The foundation for a boy's transition into adulthood and what it might entail was being laid. Young boys would have been under patria potestas and would have remained under the power of their fathers until their father's death; no coming of age or rite of passage liberated sons from this position.

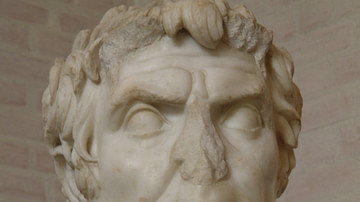

Nevertheless, the ceremony of assuming the toga virilis was a defining moment in a boy's life. The decision of what age a boy was ready for the rite of passage and to be enrolled as a citizen was taken by his father or guardian, but the ceremony tended to happen between a boy's 14th and 17th birthday. The statesman, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), marked his coming of age at 16, his son Marcus at this age, too, while the first Roman emperor Augustus (l. 63 BCE to 14 CE), as a young Octavian was just 15 years old, and Emperor Marcus Aurelius (l. 121-180 CE) assumed his toga at 16. A popular day chosen for this significant event in the life of the boy and his family was the 17th of March, at the festival of Liber, although other dates were equally acceptable.

The Toga Virilis

The celebrations began in the lararium, which was most commonly located in the atrium of the homes of affluent Romans. It was here in the lararium that the young boy, in the presence of his family and friends, would dedicate his apotropaic locket, known as a bulla, which he had worn throughout childhood to protect him from physical and moral danger. The bulla would be hung on the statue of Lares. At the ceremony, the boy put aside his childhood toga praetexta and prepared himself to receive the pure white toga virilis, the adult toga. Clothing in Roman culture could hold immense power; the toga symbolised many key aspects of what it meant to be a Roman male, and the toga virilis indicated not only that the wearer was a freeborn citizen but also his age and socio-economic status.

This assuming of the adult toga was without doubt quite a momentous event in the life of a Roman boy, it indicated the end of his childhood and the beginnings of adulthood with all its accompanying freedoms and responsibilities. This loosely draped garment was made from an oval-shaped piece of material, and it had voluminous folds; one had to learn to put it on as it required some skill to drape. It was considered the ceremonial or formal dress of Roman citizens rather than their everyday wear, but it was expected of male citizens that they dress in the toga for all civic occasions. Aulus Gellius (c. 125-180 CE) writing in Noctae Atticae, tells of an episode that occurred when he was with his oratory teacher, who it seems held to strict standards of dress, and on spotting some of his pupils who were on holidays wearing tunics and sandals instead of togas, reprimanded them and reminded them that they were senators of the Roman people and should be dressed as such (13.22).

By the late Roman Republic, the toga was certainly associated with Roman identity and probably one of the most telling indications of the centrality of the toga to Roman history was that those who were banished from Rome were forbidden to wear it. The transition from the wearing of the childhood toga praetexta with its purple band along the bottom edge to the adult plain white toga virilis was a privilege associated only with the freeborn male child. Before donning this adult toga, the boy would put on a tunic given to him by his father, known as a tunica recta. He then received the white toga from his father signifying the beginnings of his transition from boy to adult man.

Public Celebration

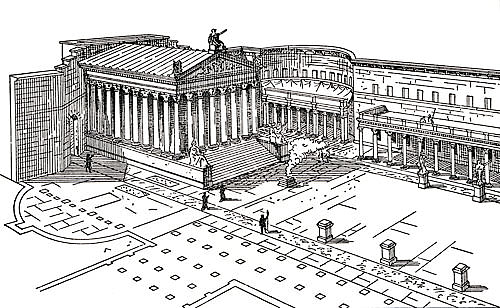

Once the celebrations at home had been completed the concluding rituals in Rome continued with the young togati accompanied by his father and family proceeding to the Forum and the Capitoline, (from the time of Augustus' reign, the ceremony took place at the Forum of Augustus). The philosopher, Seneca (c. 4 BCE to 65 CE), writing in his Epistulae Morales to Lucilius, provides us with an insight into the emotional day as he refers to cherished memories of joy felt when putting aside the childhood toga, assuming the adult toga virilis, and being escorted to the forum. The setting of the forum and its representations, such as the statues of Aeneas and his father, Anchises, encouraged the idea of filial responsibilities and obligations and stressed the duty of the young man to his parents, his ancestors, and the state.

This part of the celebration may have been known as the ad Capitolium ire, that is, "going to the Capitoline Hill", where young togati sacrificed to Liber. On the Capitol the boy may also have performed sacrifices to Jupiter and Juventas in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and at this point, he may have deposited a coin in Juventas' small shrine in the Capitoline temple or at her temple near the Circus Maximus. The young boy's complete name may have been registered in the list of citizens in the tabularium, the state record office housed in the Temple of Saturn. We also find in an early 2nd-century CE document, understood to be a 'certificate of the toga pura', a list of the names of the recent boys acquiring the toga virilis. It was displayed in the Forum Augustus while copies may have been kept in local records offices in other provinces.

Once all the rituals were completed the young boy, his family, and friends may have proceeded once again through the Forum. People would have gathered to wish the young togati well, Ovid (Fasti 3.787-788) mentions the crowds around the young boy; these crowds would have also benefited from the custom of sportulae, gifts of money or food distributed by the family.

By the 2nd century, the ceremony had become part of Roman daily life, and such ceremonies took place throughout Italy, and the practice also spread to the provinces. Young boys of elite families who possessed Roman citizenship in the Greek cities would have taken the adult toga in a similar ceremony celebrated publicly.

Concerns for the Youth

In antiquity, youth was considered a critical age of tensions and conflicts. Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 to c.170 CE) goes as far as to describe the period as a sort of frenzy, which overtook the young man and could result in a blindness of judgement in many areas of his life (4.10. 203-7). Pseudo Plutarch advises that the impulses of young men should therefore be restrained by supervision. Cicero speaks of one way of restraining youthful exuberance and that was to limit the mobility of the new togati by a unique mode of dress that he notes was used in the 1st century BCE. He says that when he was young, boys in training usually spent a year keeping one arm partially in their togas, the toga was worn so that the left arm was mostly immoblised and the right freed only to accommodate moderate gestures (Cael. 5.11). Seneca the Elder (54 BCE to c. 39 CE), when referring to the old days, says that it would have been outrageous for a young man, who was beginning his career and who was expected to convey modesty, to have his arm out of his toga (Controv.5.6).

Doubtless, the newly attained freedoms accompanying this rite of passage may have been overwhelming and sometimes would have been abused by some young men. Assuming the toga virilis meant that the young man could now marry, with parental consent; he had acquired full citizenship, social freedom, and sexual freedom. For some young boys, as we learn from the personal experience of the satirist, Perseus Flaccius (34-62 CE), who was 16 when he assumed the adult toga, there was a feeling of vulnerability on having lost the protection of the bulla and toga praetexta. This sense of vulnerability was heightened when he knew that he could do things that were once off limits such as freely wander through the Subura, the red-light district of Rome (Sat, 5. 30-6).

Cicero referred to the stage of adolescence as having " ...many slippery paths on which this age can barely stand or walk without falling or slipping" (Pro. Cael. 17. 41). He wrote of his own concerns for his nephew who was in his charge and for his son, Marcus. Marcus having already spent some time in the military sphere joined fellow Roman students in Athens to advance his studies. We learn while in Athens he certainly tested his independence and his father's patience with his partying and neglect of his studies (Ad Fam.16.21.2.).

Training for the new Togati

Rite of passage did not automatically imply that the youth became an adult and a responsible citizen. Originally, in the Roman Republic, a young man became liable for military service at 17 years old, marking the end of childhood and the beginning of adulthood. From the 1st century BCE onwards, most citizens did not serve in the Roman army, and the age of rite of passage was lowered. Tirocinium militae and tirocinium fori marked a period of time in which the youth, would prepare for life. The tirocinium militae included training in weaponry and martial exercises carried out under the supervision of an elder statesman, while the tirocinium fori provided training in political and forensic life. It was considered vital for the young togati to receive guidance from an older man who would help shape his character and provide counsel and direction, thus, the youth was placed under the supervision of such a person who may have been a successful orator, politician, or lawyer.

The period of tirocinium usually lasted a year. Cicero writes of his own assuming of the toga and being introduced by his father to the augur Scaevola; the young Cicero stayed by Scaevola's side gaining much profit from studying Scaevola's legal skills (Amic.1). Later in life, Cicero also wrote in defense of a young man who was once in his charge, Caelius Rufus. Caelius' training had been put into the hands of Cicero and the statesman Marcus Licinius Crassus (c. 115-53 BCE). Both advised and chaperoned him, and Caelius did not see anyone without the presence of his father or his mentors, Cicero or Crassus. However, when Caelius turned 19 and this supervision and tutelage came to an end, Caelius indulged in reckless pleasures and passions, which led him down the wrong path.

For young men in general, they waited until the age of 25 before being considered a full adult; this period of time was sometimes referred to as iuventas and adulescentia. Two laws, the Lex Plaetoria (c. 200 BCE) and Lex Villia Annalis (180 BCE) prevented young men from taking an active part in business or holding a position in the Roman government before the age of at least 25. Election to office was seen as the final stage in a young man's transition from youth to adulthood. By the Augustan period, a young man of 25 could become a praetor.