In ancient Rome, the legally acceptable age for marriage for girls was twelve. Although in middle-class Roman society, the most common age of first marriage for a girl was mid-to-late teens, evidence also shows that in a section of elite society, marrying off daughters at twelve or sometimes earlier was not uncommon. Traditionally, the father, the paterfamilias, and his family council arranged the marriage.

Adolescence

Formal elementary education for girls in ancient Rome would have finished at the age of twelve, however, some upper-class families chose to give their daughters further literary education. At this pivotal period in a young girl's life, as she moved out of childhood, the attention focused on a differently styled life, one which fostered modesty, decorum, and chastity; preparing the ground for marriage and motherhood. Indeed, it appears that adolescence for a Roman girl was brief and, in some cases, it seems non-existent; the inscriptions found on Roman funerary stones highlight society's expectations that a young girl behave in a way that was more adult-like in nature, indicating a cultural tendency to view young girls with qualities far beyond their years. Pliny the Younger (61-112 CE) echoed such sentiments when he wrote of a 13-year-old girl, engaged to be married, who combined the wisdom of age and the dignity of womanhood (Ep. 5.16).

As love, sex, and marriage in ancient Rome were defined by the patriarchy, from this adolescent period, when a girl was developing physically and acquiring sexual attractiveness, her life was carefully regulated in order to protect and preserve her virginity for her future husband.

Betrothal

Betrothal was not a requirement, however, it often preceded an elite marriage and might last for two years or more. Roman society put great importance on marriage to a virgin; relationships secured by early betrothal could preserve a girl's virginity for her husband-to-be. Betrothals could be entered at a very young age, especially in elite society, but a girl could be no younger than seven years old. The betrothal was usually arranged by negotiation between a girl's father and the prospective groom, sometimes acting through intermediaries.

The 3rd-century Roman jurist Ulpian (d. 228 CE), writing in the Digest, states that it does not make a difference whether the betrothal is carried out face to face or done through an intermediary; in fact, an absent person could be betrothed to another absent person. Ulpian does note that both spouses should agree to the marriage arrangement for the marriage to be considered legitimate (Ulp. 5,2). In theory, at least, the consent of the couple was required, but in practice, it appears it was often assumed. Certainly, a young girl who finds herself in a position of having little life experience to equip her to have her say or who finds that there is pressure exerted to marry the chosen spouse may duly obey her father. Ulpian clarifies that if a daughter does not fight against her father's wishes, she is understood to have consented. Of course, we must consider that there were situations where a father's affection for his daughter would mean that he would not force her into a union against her will.

The betrothed individuals differed greatly in life experience; a Roman girl's marriage most often coincided with the age of menarche, and as a result, she appears to have socially transformed rapidly from girl to virgin to wife. A girl's rite of passage into adulthood via marriage, saw her life irrevocably transformed, as a wife, a matrona, she would be required to be chaste, pious, modest, stay-at-home, and devoted to her husband. A Roman boy's rite of passage, on the other hand, saw him assume the adult toga and acquire full citizenship, social freedom, and sexual freedom. These prospective husbands would have, by their early twenties, completed an extensive Roman education, with many from elite society having studied abroad. Roman students in Athens, for example, would have enjoyed the freedoms and experiences of a 'university' life. While a young man may have transitioned into adulthood through gradual stages and worldly experiences, a young girl transitioned on the day of her marriage.

Marrying of Daughters

The Roman institution of marriage tended to be defined by customs and the families involved rather than by legal stipulations. Roman law stated that a union was established if the couple intended it to be so, and they could express their intent by living together as man and wife. Girls looked to marriage as their future; the funerary stone of a young girl speaks of her own and her parents' expectations: "My age had already fulfilled two times six years and was offering hope of marriage" (CIL 9.1817). However, the choice not to marry does not appear to have been an option, and to leave a daughter unmarried was unwise.

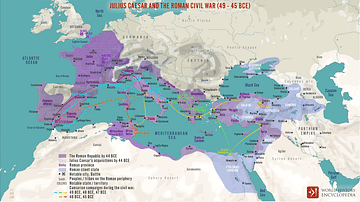

The selection of a husband for a young daughter was a family affair, with the father making the final decision. The marriage of daughters could and often did play an important role in enhancing family and wealth status. In the upper levels of society, marriages were often arranged with the purpose of creating alliances between prominent families, strengthening and extending the father's or family's power base. Used tactically, the marriage of Roman aristocrats formed ties between powerful political patrician houses. One particular web of alliances orchestrated by Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), had the Roman senator, Cato the Younger (95-46 BCE), proclaim that it was disgraceful that Roman power should now be based on trading women.

Marriage between young girls and much older men was acceptable and not uncommon in first-time marriages for girls. It appears, according to some scholarly opinion, that there was a clear preference amongst older men who had lost a previous wife to marry a girl near the beginning of her childbearing years and at the height of her physical attractiveness. Elite society provides several examples of young girls being given in marriage to men as old or older than their fathers. The statesman, Marcus Tullius Cicero (c. 106-43 BCE) was in his 60s, when, after his failed marriage to Terentia, he married his young teenage ward. The educator and rhetor, Quintilian (35 to c. 96 CE), married a girl of around 12 years old, with whom he had two children before she died aged only 18. Roman Emperor Augustus' (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) daughter, Julia, was married twice before she was 18; her second husband being as old as her father. At the age of 40, Pliny the Younger having no children, married his third wife, a young 15-year-old girl, with the hope of starting a family in his later years (Ep. 8.10/11).

We do not have any available sources that provide us with a girl's thoughts or feelings on these events, literary texts are written by male authors, providing us with a male perspective. However, we might consider that these relationships between couples with such a disparity in age, education, and experience must have been very challenging for a young girl; Pliny in referring to his own young wife, goes some way to acknowledging such challenges and comments that she has adapted well and that her devotion to him is a sure indication of her virtue.

The Marriage Ceremony

In Roman law, marriage with manus meant that the girl was no longer under the power of her father; the bride came under the authority of her husband. Manus could be regarded as 'filiae loco' meaning that the young bride was in the situation of a daughter in relation to her husband. Everything the new wife owned belonged to her husband. By the time of the 1st century BCE, marriage without manus was more common, and now the wife remained under the authority of her own father, and this also meant that the property of the spouses remained distinct.

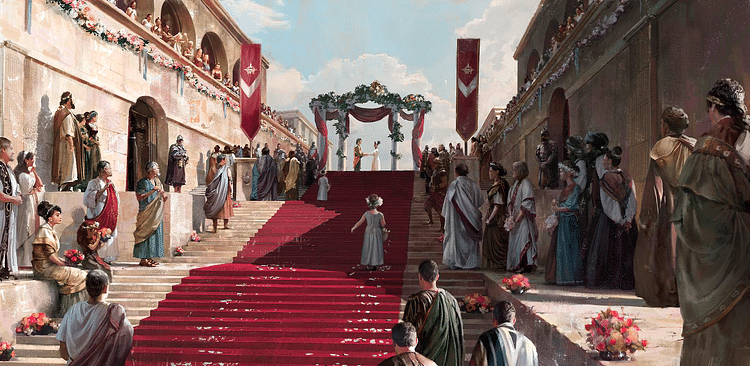

Roman law did not require a religious or secular ceremony to validate a marriage, however, many young brides marked their day with such a ceremony. On the day of her marriage, the young bride wore her hair arranged in six plaits bound by woollen fillets. Her hair was parted by an unusual instrument, a bent spear hook. A garland of flowers was worn on top of her plaits and covered by a bright yellow-orange veil, the flammeum, which covered her face and hair. Her white tunic, which the girl had woven herself, was tied with a belt; the bride may have worn yellow shoes.

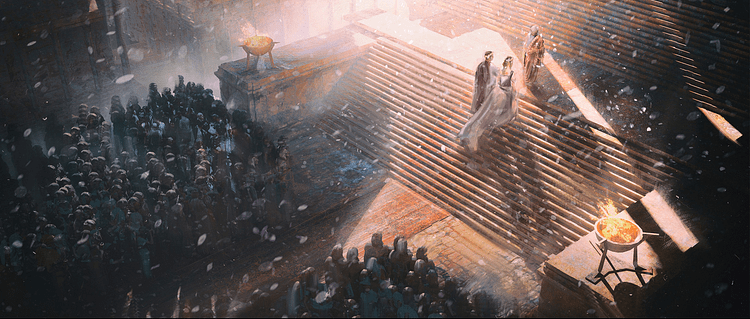

The wedding began in her father's house, which would have been decorated with garlands. Sacrifices to the gods were carried out and may have included dedicating the young girl's dolls to Venus. The banquet and wedding celebrations followed. Any contracts, such as those recording who brought what property to the marriage, were also witnessed here. In statues and relief sculptures of marriage ceremonies, it is not uncommon to see the groom holding a papyrus scroll, which may represent the records of the marriage and dowry agreement. Only after darkness would the bride be taken in a procession to the groom's house; at this point, he had already returned to the house to await his new wife. She would be led by torchlight by three boys, one of whom carried a special torch lit from the bride's hearth, the other two boys would hold her hands. Someone else would carry a distaff and spindle signifying the bride's new domestic role. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) writes of nuts being thrown at a wedding to symbolise a bride's fertility (HN. 15.86). Crowds would have gathered en route to view the bride in the procession to the groom's house. When the young girl arrived at her husband's house she ritually anointed the doorposts with oil and adorned them with woollen fillets; the bride was then carried across the threshold by her attendants, not by her husband.

Motherhood

Marriage for the Romans was regarded as the institution for the production of legitimate children. Childbirth in ancient Rome experienced high rates of mortality for newborns and mothers. High birth mortality could be compensated by high fertility, which is achieved when a wife's reproductive capabilities are utilised to the full; as a result, the age of marriage for girls was connected with fertility. For the very young bride of twelve, menarche may not begin for another two years, at which time a young girl of 14 may be able to conceive, however, pregnancy at such a young age, before the female body reaches full growth or maturity, carries much risk.

Ancient medical understanding of when a young girl was physically capable to conceive and carry through a pregnancy led some writers on Roman medicine, such as the physician Rufus of Ephesus (c. 70 to c. 110 CE), to confront the problem of risk versus the pressure from society to begin a family. Rufus rejected the notion that girls marry young and start having children at the age of menarche; he argued that pregnancy was extremely unsafe for a young girl and that the wisest decision was to wait until 18.

Puberty is not a favourable time for childbearing, either for the child or the mother. The former is sure to be weak while the latter, distressed before her time, comes to grief and exhibits a damaged womb.

(Rufus, QM 6.22)

Soranus (98-138 CE) writing in his Gynaecology, also questioned those risks that were taken with a young wife's health. Soranus advises termination be considered for very young girls who were having serious difficulties during pregnancy in order to prevent any further danger if their uterus was too small and not ready to accommodate full development. However, medical advice and opinion were intended to inform and advise whilst also cooperating with Roman society's expectations; elite social and familial pressure continued to encourage the movement of young girls directly from puberty into marriage and childbirth.

Conclusion

For young girls, marriage signified the end of childhood in ancient Rome. It changed a young girl's life and identity. No longer a child she was now a wife, embarking on a sexual life and all its consequences, taking on duties and responsibilities of a household and dedicating herself to her new husband and the role of women in the Roman world.