Pharsalus, in eastern Greece, was the site of a decisive battle in 48 BCE between two of Rome's greatest ever generals: Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar. After several previous encounters, Pharsalus, the biggest ever battle between Romans, would finally decide which of the two men would rule the Roman world. Outnumbered in infantry and cavalry, Caesar employed daring strategies which won him a resounding victory and, in so doing, he cemented his reputation as one of the greatest commanders in history.

Prologue

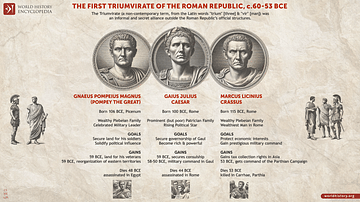

The immensely popular Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, otherwise known as Pompey the Great, had enjoyed great military successes in Sicily and Africa, he had emphatically swept the Mediterranean clear of pirates and, most impressively of all, he had defeated Mithridates VI in the east. Ruling as a triumvirate with Julius Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus, Pompey governed Rome's Spanish provinces whilst Caesar, now rich from his own glorious conquests, controlled Gaul. In the final years of the Roman Republic and following Crassus' untimely death in 53 BCE, the two remaining rulers became set on a collision course to disaster.

Pompey, always big on preparation and wary of the inevitable confrontation with Caesar, decided that his best strategy was to abandon Italy. Loyalties there were divided and the two legions present could not be trusted to face their old commander Caesar. Instead, Pompey chose to gather his legions in Greece in 49 BCE. Caesar almost caught Pompey's army before it left Brundisium in southern Italy but, escaping a partial blockade of the harbour, Pompey fled to fight another day. There still remained the problem of seven legions loyal to Pompey in Spain, but now Caesar controlled the treasury of Rome and, after making a few select appointments of who governed where in the provinces, he turned his attention to this dangerous threat to his rear. Within seven months these legions had been subdued, and on the way back to Italy the siege of Massilia was completed as an added bonus. Nominated as dictator by Lepidus, Caesar had now built himself both a formidable reputation on the field of battle and a secure platform from which to launch a final and devastating attack on Pompey.

There had been, however, some significant setbacks for Caesar's commanders in Africa, the Adriatic, and Dolabella, and Pompey used his time well to assemble at Beroea in Thessaly nine Roman legions and an impressive multi-national force of 3,000 archers, 1,200 slingers, and 7,000 cavalry. And if that was not enough, he also had up to 600 ships at his disposal. As was typical, these were drawn from across the eastern Mediterranean and separated into smaller fleets, Marcus Bibulus being given the responsibility of overall command. The numbers were impressive but the exotic mix of nationalities, their preparedness, and their loyalty to the Republic when it came to the crunch were questioned, notably by Cicero.

With the support of the Roman upper classes, Pompey was officially made commander-in-chief of the Republic's armies, and he marched to establish a winter camp on the west coast of Greece. Late in the season, it now seemed that an engagement would have to wait until the following spring but then Caesar did the unthinkable. Despite the threat of Pompey's navy and the risks of a winter crossing, Caesar, true to his own maxim 'the mightiest weapon of war is surprise', mustered as much of his army as possible and, without the usual baggage or slaves, sailed to Greece on the 4th of January. He landed at Palaeste right under the nose of Pompey's fleet stationed on Corcyra. With the navy slow to react, Caesar wasted no time and started sacking cities while Pompey was forced to head him off at the river Apsus, where each side stationed themself on opposite river banks.

Mark Antony, Caesar's trusted second-in-command, finally arrived in April with a second force which boosted Caesar's legions to eleven. Both sides now moved around Thessaly trying to control the region and prevent more reinforcements arriving to their opponent until they faced off again, this time at Asparagium. The legions now facing each other were seven with Caesar and nine with Pompey, who, confident he could harass Caesar's supply lines, was in no rush for an all-out battle. Eventually, he set up camp at Dyrrachium, but Caesar immediately began an audacious project to construct an enclosing wall to ensure Pompey was boxed in against the sea. Tempting Caesar into an attack by using false traitors who promised to open the camp gates, Pompey threw all he could at his opponent, including naval artillery fire. Caesar managed to retreat but was attacked again, and this time Pompey went for the weak points in the siege walls, information given to him by two defecting cavalry commanders. In the confusion which followed, Pompey established a new camp south of Caesar's walls. However, on the 9th of July, at the moment Pompey's forces were split between the old and new camps, Caesar attacked the former, forcing Pompey to send five legions to extricate their comrades. Caesar's troops took a battering but Pompey did not press home his advantage, and he would never again get such an opportunity against his nemesis. Caesar famously judged Pompey's lack of initiative as evidence that, 'he does not know how to win wars'.

Regrouping and finally recognising that his blockade was futile, Caesar withdrew to the south. Pompey sent his cavalry in pursuit, but Caesar managed to escape to the plain of Thessaly in Greece where he set up camp on the north bank of the River Enipeus between Pharsalus and Palaepharsalus. Pompey and his army arrived on the scene shortly after, setting up his own camp one mile to the west in the nearby low hills - a good strategic position which ensured a safe route for supplies. The stage was finally set for a decisive resolution to just who would control the Roman Empire.

Commanders

Julius Caesar was noted for his use of speed (celeritas) and surprise (improvisum) in his military conquests. Often choosing to attack with the troops at his disposal rather than waiting to amass a larger force and establish secure supply lines, Caesar stored great faith in his own leadership skills and the fighting prowess of his legions. Fortunately, time and again, his enemies obliged Caesar with exactly what he wanted - make or break set-piece battles - and Pharsalus would follow the same pattern.

Mark Antony was Caesar's able and experienced second-in-command, and he would lead the left wing at Pharsalus. Domitius Calvinus, the one-time tribune and consul, took the centre. Publius Cornelius Sulla (nephew of Sulla), who had skillfully contained Pompey at Dyrrachium, would lead the right wing.

Pompey enjoyed a great reputation as a military leader following his string of successes and was particularly noted for his meticulous planning and attention to detail. He had perhaps, though, become too cautious on the battlefield in his later years, and he lacked the dash and daring that could grasp a victory when things were not going well or according to plan, skills his opposing commander was all too accomplished at.

Pompey's command was bolstered by the inclusion of Titus Labienus, Caesar's second-in-command for much of the Gallic campaign but who had since defected to the Republican side; he would command the large cavalry force at Pharsalus. Leading the centre at Pharsalus was Scipio Metellus, a past consul who had enjoyed success in Syria, whilst Africanus would command the right wing and Ahenobarbus the left.

Battle Positions

Caesar was keen to settle the issue immediately, but Pompey proved unwilling to abandon his advantage of high ground. After several days and seeing the stalemate, Caesar decided to pack up camp and leave in the hope of engaging Pompey somewhere else. However, early in the morning of the 9th of August, Pompey inexplicably moved his troops onto the plain. Here was Caesar's chance. Abandoning their baggage and even knocking down their own defences to better allow the troops onto the battlefield, Caesar's troops marched post-haste to finally meet the enemy.

Perhaps Pompey had finally tired of the cat-and-mouse game, maybe he wanted to capitalise on his men's good morale following the victory at Dyrrachium, or perhaps he thought it intolerable to lose face and watch his enemy march off only to create havoc at a later date. Pompey would also have been under pressure from senators eager to free the Republic from Caesar's menace. Whatever the reason, he had given away his advantage of high ground and now the two armies met on the plain below.

Pompey fielded eleven legions, a total of 47,000 men. 110 cohorts lined up in the triplica acies formation - four cohorts in the first line, three each in the second and third line. The bulk of the cavalry, archers, and slingers held the far left flank up against the low hills, while a smaller cavalry and light infantry force was stationed on the far right up against the river Enipeus. The best troops took their place on the wings and in the centre, with veterans being dispersed throughout in order to support troops new to battle conditions. The full length of the front line would have been around 4 km. Pompey's plan was to send his cavalry around the enemy flank and attack from the rear. Meanwhile, the infantry would press forward and Caesar's army would be crushed between the two movements. Pompey himself commanded the field from his position to the rear of the left wing.

Caesar lined up his troops to mirror Pompey's positions but to do so he had to thin out his lines. At his disposal were only 9 legions totalling 22,000 men divided into 80 cohorts, significantly fewer than his opponent. Caesar positioned himself opposite Pompey, behind his best legion, the X, on the right wing. His light infantry were placed right of centre. As a precaution against Pompey's superior cavalry numbers (6,700 against 1,000), Caesar moved six cohorts (2,000 men) from his rear line to act as a reserve on his right flank, placing them at an oblique angle.

Attack

Pompey attacked first using his cavalry and he drew a countercharge from Caesar's cavalry. Meanwhile, Caesar's front two infantry lines attacked and engaged all three lines of Pompey's infantry who stood their ground rather than employing the traditional advance to meet the oncoming enemy. This tactic may have been to tire Caesar's infantry by making them cover more ground, to ensure his own cavalry had less ground to cover in going behind the enemy, or simply because Pompey wanted to maintain good battle order. However, seeing that Pompey's lines were not advancing, Caesar's legions halted, regrouped, and, after a quick breather, carried on their charge. Caesar deliberately kept back his own third line of infantry. The first weapons thrown were the javelins (pila), a volley from either side. Then the enemies met with a clash of shields and thrusting swords.

Through sheer weight of numbers Pompey's cavalry overwhelmed the enemy cavalry and got behind Caesar's infantry. Now, as Pompey's cavalry were reorganising into smaller squadrons, Caesar took the opportunity to attack. Having withdrawn what was left of his own cavalry (perhaps this was a pre-meditated strategy) he sent in his six reserve infantry cohorts telling his men to aim their javelins at the enemies' faces. The unexpected attack threw the republican cavalry into a panic and they bolted from the field in confusion. This left Pompey's slingers and archers at the rear open to attack. In the confused cavalry retreat, the attack of Caesar's reserve and possibly also the re-introduction of Caesar's reduced cavalry force, resulted in a complete rout and left Pompey's left wing entirely exposed. Having engaged all three lines of his infantry Pompey had no contingency force to deal with this new threat and it was precisely at this moment that Caesar unleashed his third line of infantry into the battle.

Pompey's troops initially resisted the onslaught and kept a disciplined formation but eventually, and not helped by the probable desertion of their multi-national allied troops, the legions gave way and retreated headlong for the hills. Pompey retreated to his camp in dismay and then left the field completely, riding for Larissa with a small loyal escort, rather ingloriously disguising himself as an ordinary soldier. Caesar pressed home his advantage and wiped out Pompey's camp causing the rest of Pompey's army to flee to the Kaloyiros hill. Caesar besieged the hill and with four legions cut off the army when it also tried to retreat to Larissa. On the morning of the 10th, Pompey's army surrendered their arms. Caesar claimed to have wiped out 15,000 of the enemy, but the figure was more likely around 6,000 dead on the Republican side for the loss of 1,200 of Caesar's legionaries. Most of the republican leaders fled the battlefield, hoping to carry on the war from Africa, but victory was Caesar's.

Aftermath

Arriving by way of Cyprus, Pompey tried to convince the Egyptians to be his ally, but he was callously murdered on 28th September 48 BCE. Egypt had hoped to win Caesar's favour by presenting the head and signet ring of his once great enemy but, in fact, Caesar was said to have been moved to tears when he saw the fate of his rival. Restoring Cleopatra VII to the throne of Egypt and defeating the last republican armies in Africa, Caesar returned to Rome in triumph in 46 BCE. Then, when the last remnants of opposition were defeated in Spain, Julius Caesar stood alone, the most powerful individual in the Roman world and, the final cherry on the cake, in February 44 BCE the Senate voted him dictator for life.