The Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE was an all-Roman affair fought between the young Octavian, chosen heir of Julius Caesar, and the mercurial Mark Antony, widely regarded as the greatest living Roman general on the one side against Brutus and Cassius, the assassins of Caesar and champions of the Republican cause on the other. The battle, on an inland plain in eastern Macedonia near the city of Philippi, would involve the largest Roman armies to ever take the field and, as 36 legions clashed, the bloody outcome would decide the future of the Roman Empire and finally bring to an end the 500-year old Roman Republic.

Prologue

In 44 BCE Mark Antony and Gaius Octavian, Caesar's most accomplished general and his chosen heir respectively, formed an uneasy alliance to take revenge on the dictator's assassins and restore order to the Republic. After an initial reconciliation with the conspirators Antony tried to marginalise Brutus and Cassius by appointing them supervisors of Rome's grain supply from Asia and Sicily. The positions were refused and both men left Rome for the east. Octavian, meanwhile, began a successful campaign to increase his own popularity with the people by sponsoring a series of public games. Antony, though, came under attack from Cicero who wanted a fully independent Senate and who cast his support for Octavian. However, even if Antony was coming off second-best in the political arena, he still had control of the army, and he brought four of his Macedonian legions to Italy to drive home the strength of his position.

Events took a twist when Antony went to meet his legions at Brundisium in October 44 BCE. Angry at Antony's lack of decisive action against Caesar's killers, the troops had switched loyalties to Octavian who had offered them greater financial rewards. The old distinction between these two ambitious men that one had political power and the other military was now no longer the case. Further, other legions began to throw their allegiance at Octavian's feet. Antony responded by fixing that the Senate redistributed important provinces to his own loyal supporters. The consequence of this was the conciliation with Caesar's assassins was reversed. Decimus Brutus, another of the conspirators who had killed Caesar, ignored the re-division and, raising two legions, held station at Mutina (Modena). Antony, still with three legions at his disposal, lay siege to the fortified city. Meanwhile, and now supported by the Senate, Octavian took command of four legions and declared Antony guilty of tumultus, or civil disorder, one step short of a declaration of war against his great rival for control of the Roman Empire.

The battles around Mutina in April 43 BCE were as confused as the various conflicting accounts by ancient historians but the end result was Antony was first victorious but then partially defeated, the Republicans won but lost both consuls, and Octavian was upset not to be given a triumph by the Senate and was alienated by their decision to give Sextus Pompey command of the navy. While Octavian manipulated politics in Rome, Antony strengthened his own position and now controlled Gaul and Spain. Octavian also made his decisive move in August 43 BCE and marched his eight legions to Rome where the three Republican legions promptly switched sides and Octavian became consul at the unprecedented young age of 20. His position was further strengthened when he was joined by six more ex-Republican legions. Octavian, now with 17 legions at his disposal, turned his full attention to Antony, who had 20 legions and 10,000 cavalry under his command. Even now though, diplomacy prevailed and the three leading Romans - Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus - met in November 43 BCE to discuss terms and form the Second Triumvirate where each member was given carte blanche power for five years in their respective zones of the empire. The legions were re-shuffled so that Lepidus had three legions in Rome and Octavian and Antony each had 20. Vicious revenge was then taken on Republican supporters in Rome and such notable figures as Cicero were executed.

Meanwhile, Brutus collected his army in upper Macedonia whilst Cassius amassed 12 legions in Judea. In 43 BCE the two joined forces at Smyrna. Then, after successful campaigns against Rhodes and Xanthus, the two took position at Philippi on the Hellespont in September 42 BCE. The third threat to Octavian and Antony was Sextus Pompey whose large naval fleet had helped him take control of Sicily in December 43 BCE. Octavian, unable to overwhelm Sextus, instead heeded Antony's request to fight together against the larger threat of Brutus and Cassius. From Brundisium the two armies crossed the Adriatic. For the first time, the opposing legions were in close proximity and ready for battle.

Commanders

Marcus Junius Brutus, although previously successful in smaller conflicts in Thrace and Lycia, has been judged by history as a little too soft and lacking in authority when it came to the serious generalship of commanding large armies in set-piece battles and, consequently, he has been described as more of a statesman than a military commander by many historians. The other Republican leader Gaius Cassius Longinus, on the other hand, had gained a reputation as an astute general and tough disciplinarian - defeating the Parthians in 51 BCE and half of Julius Caesar's fleet during the Civil War, when he sided with Pompey. This pair, then, were an odd but formidable commanding team but it was their bad luck that they now happened to face two of Rome's greatest ever leaders.

Marcus Antonius, better known as Mark Antony, had already enjoyed a glittering military career by the time of Philippi with a long series of successes as Caesar's right-hand man and Master of the Horse. Antony was notoriously bad at leadership in peace time and all too easily neglected politics for wild parties but in the chaos and horror of battle he was second-to-none. His ally, albeit one of pure convenience to defeat a common enemy, was Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. Technically, Octavian, chosen heir of the now deified Julius Caesar, was the son of a god but this disguised his relatively modest background. Octavian would go on to become the first, and arguably greatest ever, Roman emperor but at Philippi he was still a young and inexperienced commander, even worse, he was beset with health problems during the battle and so it was Antony who would, as so many times before, steal the military lime-light. Daring and incautious but so often lucky, Antony would once more excel in the role he was seemingly born for.

Armies & Weapons

The two Roman armies which clashed at Philippi were composed of the now well-established military units, the legions. A legion was composed of 4,800 men broken down into 10 cohorts and 60 centuries. Each legion was commanded by a legate (legati) who was aided by military tribunes (tribunimilitum). Each century was led from the front by a centurion and a sergeant (tesserarius) whilst an optio (deputy) marshalled the rear. An ordinary legionary was armed with a gladius short sword (double-edged and around 60 cm long), a pilum spear or javelin, a pugio dagger, and he had a scutum shield (around a metre tall, made of wood and edged with iron), mail armour, and helmet for protection. Supplementing each legion were a force of 300 cavalry, and slingers, archers and other light-armed auxiliaries.

Opening Positions

The battle would involve the largest number of troops in Roman warfare up to that point. 19 legions of 110,000 men on the Triumvirate side faced 17 Republican legions of 90,000 men. The Triumvirs had a force of 13,000 cavalry and one extra legion stationed at nearby Amphipolis whilst the Republicans had two legions guarding the fleet and a cavalry force of 17,000 on the plain. The Republican army was then, not only smaller but it also consisted of a much more varied mix of troops taken from across the empire. On top of that, many of the veterans and all-important centurions had fought many times for Julius Caesar, and so to now face his heir and best general must have severely tested the troops' resolve and loyalty.

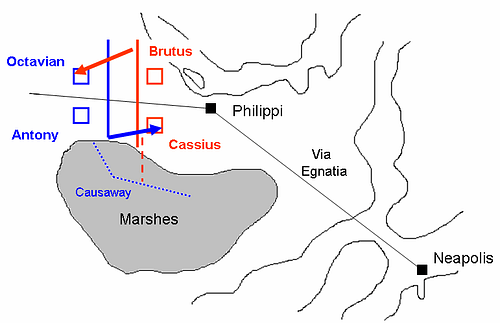

In the field Cassius took advantage of two mounds located above the plain of Philippi to make two fortified camps for his nine legions. Brutus and his eight legions camped at the foot of the mountains and a palisaded corridor was built to connect the two Republican armies. Both camps received additional protection from the Gangites River. The two camps were a significant 2.7 km apart though, which meant the two armies could not easily offer mutual support. Antony, therefore, concentrated on Cassius' camp and, with typical bravado, established his army of ten legions in a well-fortified camp a mere 1.5 km from the enemy. Ten days later, Octavian's army of nine legions arrived. Nevertheless, the Republicans had all the advantages of a better supply line and an elevated position so that time was on their side. The Triumvirs would have to take the initiative.

First Battle of Philippi

Several early attempts by Antony and Octavian to draw the enemy down to the plain failed completely. As a consequence, Antony, while still making a show of troop manoeuvres on the plain, attempted to cross the reed marshes undetected by building a causeway and, when behind the Republican camps, try to cut their supply lines. Cassius soon got wind of the strategy and responded by trying to cut off Antony's advance forces by himself building a transverse wall from his camp to the marshes. Seeing his plan had been discovered, on October 3rd, Antony led a direct assault on Cassius' wall overwhelming the stunned left flank of the enemy and destroying their fortifications. Then, while the bulk of Cassius' army was engaged on the plain, Antony went straight for Cassius's largely undefended camp. As things swung against Cassius' legions on the plain and when they saw their camp routed a chaotic retreat followed.

Meanwhile Brutus was doing well against Octavian's legions who, caught by a surprise charge from Brutus' over-eager advance troops which had necessitated the whole Republican army mobilising in support, were routed in a chaotic battle during which Octavian's camp was captured. Fortunately, Octavian - ill again and missing the battle - had taken refuge in the marshes and avoided certain capture. Brutus, on discovering the loss of Cassius' camp, sent reinforcements but Cassius, holding out with a small force on the acropolis of Philippi, interpreted them as more of Antony's forces and so committed suicide - as it happened, on his birthday - rather than be captured. While all this was happening Antony and Octavian's reserve troops, arriving by sea, were destroyed crossing the Adriatic by the Republican fleet. Thus, the first battle of Philippi ended, more or less, in a 1:1 draw, with 9,000 losses on the Republican side and more than double that figure from Octavian's army.

Second Battle of Philippi

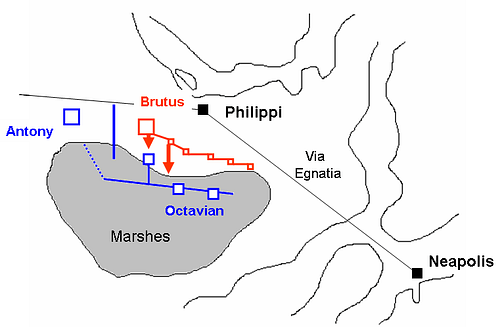

Following the first battle both sides returned to their original camps to re-group. Brutus, taking over Cassius' camp, sought to stick to his original plan of holding station until the enemy was forced to withdraw through lack of provisions. Brutus did harass the enemy via night attacks on their position and even diverting a river to wash away part of their camp. Lacking supplies and having lost their back-up in the Adriatic, Antony and Octavian had to make their move before winter really set in and forced them to leave the field. Initially, Brutus stoically resisted the repeated taunting by the enemy to come out and face them but eventually, at least according to the ancient Roman historians, ill-discipline got the upper hand and Brutus' army took their own initiative and descended to the plain.

Antony had, meanwhile, also made some daring and decisive moves. First, he took full advantage of a small mound south of Brutus' camp which the Republican leader had left unguarded (and this despite the fact that Cassius had previously stationed a garrison on it). Building a palisade of whicker, four legions were now dangerously close to Brutus' position. At the same time Antony moved ten legions into the central marsh area and two more a little further east. Brutus responded by building a fortified camp facing each of these two blocks of enemy troops but if the battle lines were extended any further then Brutus would be isolated from his supplies and backed up against the mountains -an impossible position to defend. The Republican army, then, had little choice but to engage the enemy with a full-scale assault. The time for dilly-dallying was over.

The use of artillery weapons in the confines of such a tightly-packed battlefield was considered impractical and the opposing armies immediately clashed in fearsome hand-to-hand fighting. Initially, the Republicans did well against the enemy's left wing but Brutus, with fewer troops at his disposal, had stretched his lines thin to ward of an out-flanking manoeuvre. The consequence was Antony relentlessly pushed forward and smashed the enemy centre and, moving left, attacked the rear of Brutus' lines. The order of the Republican troops now completely broke down and chaos ensued. Meanwhile, Octavian had attacked the Republican camp while Antony used his cavalry to chase down Brutus and prevent his escape. The Republican leader had found refuge in the nearby mountains but when his four remaining legions moved to plea for clemency from Antony, Brutus took his own life. In total 14,000 soldiers surrendered and while some others managed to flee by ship to Thasos, the Republican cause was at an end and Julius Caesar's murder had been avenged. In the words of Ovid, "all the daring criminals who in defiance of the gods, defiled the high priest's head [Caesar], have fallen in merited death. Philippi is witness, and those whose scattered bones whiten its earth".

Aftermath

Whilst Antony was hailed as imperator by the victors and losers alike, Octavian, who had dealt more harshly with the defeated, was not so highly esteemed. As Plutarch stated in no uncertain terms, "[Octavian] did nothing worth relating, and all the success and victory were Antony's". The legions were again re-distributed with Antony taking eight to campaign against Parthia whilst Octavian, with three, returned to Italy. The battle, with its 40,000 fatalities and subsequent retaliations against Republican sympathizers, robbed Rome of some of its finest citizens and soldiers, and still the question of just who would rule Rome was not settled. For, despite the obvious military skills of Antony, in the end, it would be Octavian's political skills and genius at inspiring loyalty from other, more talented commanders such as Marcus Agrippa, that ensured Antony was prevented from becoming Caesar. Following several more years of struggle and intrigue, it was Octavian who would be the real winner at Philippi and ultimately, following the defeat of Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, he would rule the Roman Empire as the first of a long line of Roman emperors.