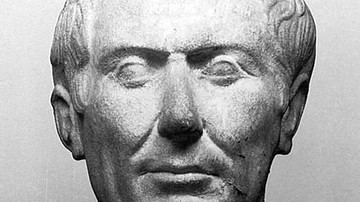

Last March marked the anniversary of Julius Caesar's assassination over 2,000 years ago, and after two millennia, his legendary achievements still linger in today's consciousness just as they have for centuries. He was so revered that in Dante's Inferno, his conspirators shared the lowest circle of hell with Judas Iscariot, labeling them the worst sinners in history. Even Alexander Hamilton claimed, “The greatest man who ever lived was Julius Caesar.” Could he really have been that great?

Early signs of his personality

Caesar was born in the slums of Rome even though he traced his lineage to the city's noble forbears and even claimed to be a descendant of the goddess Venus. Through his brilliance, tenacity, and perpetual willingness to become overwhelmed with debt, he was able to climb the political ladder, called the cursus honorum, and reach the pinnacle of power.

But the faults lingering beneath Caesar's charismatic veneer were evident very early in his life. After he was captured by pirates, ransomed, and released, he sought revenge, with good reason. He seized the pirates and turned to the Roman provincial governor to mete out justice. When he was unhappy with their sentence of slavery, he defiantly had them all crucified. Not long after, he was once again dissatisfied, this time with Rome's reaction to a threat posed by the belligerent King Mithridates. Instead of coordinating with Roman officials or even acquiring permission, he insubordinately led troops against the Mithridatic allies.

Caesar the commander

While Julius Caesar was a cunning military commander, with successes ranging from Britannia to Egypt, not all of his wars were justified. He would often seek even the most dubious of justifications to give him license to attack, invade, and conquer simply to serve his own interests. Frequently, he claimed it was for the safety of Rome, but that was a stretch. What sort of threat could Britannia pose to Rome when many Romans weren't even convinced that it existed?

As Caesar ravaged countrysides, he was not above sacking towns merely for plunder, murdering women and children, or selling countless men into slavery. However, when the southern Gallic fortress of Uxellodunum finally fell to Caesar, he spared the inhabitants' lives, but severed all of their hands. He claimed that he killed one million people in the Gallic wars alone, but he must have known that conquering, killing, and enslaving free and innocent people was immoral. After all, it was Caesar that said: “Human nature everywhere yearns for freedom and hates submitting to domination by another.”

The Triumvirate

When Caesar was unhappy with the stagnant political situation in Rome, he formed the First Triumvirate, a partnership with two other Roman power brokers, Pompey and Crassus. This partnership allowed them to control the state through violence and bribes while granting each member lucrative state positions with immunity from prosecution. Caesar wasn't timid about bribing the electorate, the Tribunes of the Plebs (sacrosanct government officials), or even Consuls (one of two executive officers). Of course this was a two-way street, and Caesar was more than willing to accept bribes too, as he did from King Ptolemy XII of Egypt.

Eventually, the First Triumvirate broke down, and without the power of the collective group, Caesar could no longer enjoy the endless benefits. After deliberation, he crossed the Rubicon and invaded Rome to enforce his will. The pretext for his costly and protracted civil war was to provide justice for the people and protect his dignitas (a Roman concept similar to honor), but it was really just a power grab. This shouldn't have surprised anyone considering that his hero was Alexander the Great, a man Marcus Tullius Cicero considered an international scourge.

The Civil War

During the ensuing civil war, Caesar tried to be on his best behavior to win the public relations battle, but sometimes he just couldn't control himself. He looted the Roman treasury, imposed fines on towns that opposed him, and pillaged farms. When the city of Gomphi refused to open their gates, he forced his way into the town. He allowed his soldiers to kill many of the men and violate the women to raise the army's morale and leave a lasting impression on the Greeks.

As the civil war was coming to a close, he forgave many of his enemies, but the Republic and the Roman Constitution were destroyed. He became dictator for life and praefectus morum (master of morality), an interesting choice for someone with no qualms about murdering innocent children, mutilating a whole city, or borrowing many of his friends' wives. He banned exotic goods and even raided private residences to confiscate contraband. He imposed rules of morality while he blatantly ignored them. He defaulted on his enormous debts while forcing others to repay their loans, but excusing himself from laws was to be expected. He built a long career upon that notion, often at the point of a gladius sword.

Dictatorship

He threw exorbitantly lavish festivities for himself, and when three of his soldiers stirred up discontent and chastised him for his waste, he had one executed and the other two ritually killed and dedicated to the god Mars. Caesar then publicly displayed their heads near the Regia, a sacred Roman temple. His bloated ego would continue to expand and go unchecked. He accepted a golden throne to mark his seat in the Senate, permitted a cult to be dedicated to himself, proclaimed his birthday a national holiday, and even renamed a month after his family – Julius (July).

For an American founding father like Alexander Hamilton to consider Julius Caesar the greatest man who ever lived is profoundly ignorant. The United States Constitution was modeled on the Roman Republic, and Caesar replaced the Roman Constitution with an autocracy, which would last for centuries. Caesar even once quipped: "The Republic is nothing, just a name without substance or form."