Time has seen the rise and fall of a number of great empires - the Babylonian, the Assyrian, the Egyptian, and lastly, the Persian. Regardless of the size or skill of their army or the capabilities of their leaders, all of these empires fell into ruin. History has demonstrated that one of the many reasons for this ultimate decline was the empire's vast size - they simply grew too large to manage, falling susceptible to external, as well as internal, forces. One of the greatest of these empires was, of course, the Roman Empire. Over the centuries it grew from a small Italian city to control land throughout Europe across the Balkans to the Middle East and into North Africa.

Population & Spread

It is, unfortunately, difficult to obtain precise figures on the number of people living at any one time in the Roman Empire. Any calculation of the population would be garnered from the census, but the Roman census may or may not have included women and children below a certain age. The census was used not only to ascertain the population but also to levy taxes and feed the populace, but since the census was based on property and citizenship, one must question who was included in the final tally. Also, slaves were probably not included, but according to one estimate, there were between 1,500,000 and 2,000,000 slaves in Italy in the 1st century BCE.

In the beginning, before the Roman Republic, the city of Rome had an estimated population of only a few thousand. By the 6th century BCE and the exile of the kings, the city had grown to between 20,000 and 30,000 inhabitants (again this may or may not have included women and children). As the city grew along with the empire, Rome became a magnet for artists, merchants, and people of all walks of life - especially those looking for work. At the beginning of the imperial period, the city had close to 1,000,000 residents. The empire during this same time had grown from 4,063,000 inhabitants in 28 BCE to 4,937,000 inhabitants in 14 CE – that is according to the census. The latter was a point of great pride for the Roman emperor, or so Augustus wrote in his Res Gestae. Augustus is quoted to have said, "I found Rome built of sun-dried bricks; I leave her clothed in marble." This quote might also reflect the empire's growth in people as well as land.

From a small city on the western edge of Italy, Rome - or the empire - had grown to include territory from the North Sea to most of the region surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. To the north were Britannia, Germania, and Gaul. To the west and southward along North Africa, the empire included Hispania, Mauretania, and Numidia. Eastward and into the Middle East were Egypt, Judea, Syria, Parthia and Asia Minor. Closer to Italy and to the east were Macedon, Greece, Moesia, and Dacia. Add to this the islands of Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily. Throughout the Roman Empire, there were cities of 100,000 to 300,000 inhabitants - Alexandria, Carthage, Antioch, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Lyons. However, like all of those before it, the Roman Empire could not endure and finally fell in 476 CE to an invasion from the north. To understand the extent of this great empire one must return to the beginning in the early 6th century BCE.

The Justification for Expansion

In 510 BCE, the monarchy that controlled Rome was overthrown, and the king Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was expelled. From that time onward - for the next several centuries - Rome continued to grow and spread its sphere of influence throughout the Mediterranean region. Despite both inside and outside forces, the sea became what has been termed a Roman lake. This astonishing growth through the early Republic extended into the age of the empire, culminating in the period of the Pax Romana - its version of peace and stability.

However, to achieve this immense expansion Rome became what one historian has called a warrior state. This constant state of war made Rome not only rich but also helped mold Roman society. Its conquest of the Balkans and Greece influenced Roman art, architecture, Roman literature and philosophy, but the growth would not continue, and in the end, the empire became less a force of conquest and more one of pacification and management. Throughout their wars of expansion, the Romans never considered themselves the aggressor. According to one historian, in their mind, Roman warfare was only meant to subdue enemies that they believed to be a viable threat to Roman integrity. The Roman statesman and author Cicero believed the only reason for war was so Rome could live in peace.

The Republic Expands In Italy

The best place to start is at the beginning: the conquest of the peninsula of Italy. After the fall of the monarchy and the creation of the Republic, the city of Rome, for whatever reason, wanted to grow beyond its seven hills, and this growth meant, first of all, conquering all of Italy. This desire did not go unnoticed by the surrounding communities, and to forestall any possible war, they formed what became known as the Latin League. Their fears came to fruition when war broke out near the city of Tusculum at Lake Regillus. During a well-fought battle, the Roman army was supposedly rallied to victory - according the legend - by the appearance on horseback of Castor and Pollux, the twin brothers of Helen of Troy. According to the treaty negotiated by Spurius Cassius Vecellinus in 393 BCE, the victory resulted in the confiscation and plunder of the Latium lands. And, as an additional condition, the Latium people had to provide Rome with soldiers for any future conflicts. This latter condition would be an addendum to all future Roman treaties. The Latin alliance with Rome helped defeat many of their closer neighbors, neighbors who had often raided Roman lands - the Sabines, Aequi and Volsci. Over time Rome took to the offense again, defeating and destroying Veii.

Despite an invasion of the Gauls from the north in 390 BCE and the near fall of the city, Rome was able to quickly rebuild - fortifying its walls - and continue its conquest of the peninsula. In the 4th century BCE the Samnites, a group of people to the southeast of Rome, captured Capua, a city located in the Campania, a province just to the south of Rome. Due to a treaty with Rome, the people of Capua appealed to the city for help. So, from 343 to 341 BCE, a series of short skirmishes occurred between Rome and the Samnites. As a result, Rome gained control of Campania. However, the conflicts, known as the Samnite Wars, would not end there.

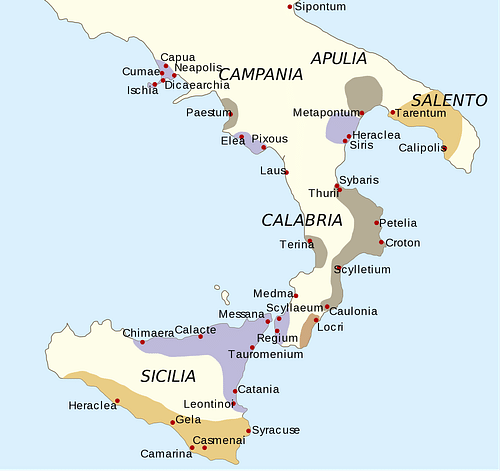

During the second series of conflicts from 327 to 304 BCE, the Samnite forces defeated the Romans at Caudine Forks in 321 BCE; however, they were unable to get Rome to back down. Afterwards, the Samnites made alliances with the Gauls, Etruscans and Umbrians, but during the Third Samnite War (298 to 290 BCE) Rome crushed the Samnites and their allies. Next, they made alliances with Apulia and Umbria. They crushed the Hernici and Aequi as well as the Marsi, Paeligini, Marrucini, Frentani and Vestini, former allies of the Samnites. Rome was now the major power of the peninsula and to secure this power they established colonies throughout Italy. The Romans now turned their eyes to the south.

The city of Tarentum, fearing Rome and realizing they were next, appealed to Pyrrhus, king of the western Balkan province of Epirus. Since the city had helped him in the past, the king answered their appeal and sent his army of 21,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and 20 elephants to southern Italy. The king proved victorious over Rome twice - at Heraclea in 280 BCE and Asculum in 279 BCE. However, as during the early wars with the Samnites, the Romans would not admit defeat and soon recovered, and at Beneventium Rome was victorious. By 270 BCE all of Magna Graecia - the areas along the southern boot of Italy - was annexed by the Roman legions. However, this expansion eventually brought them in conflict with another great city across the sea, Carthage.

The Punic Wars - Expanding South

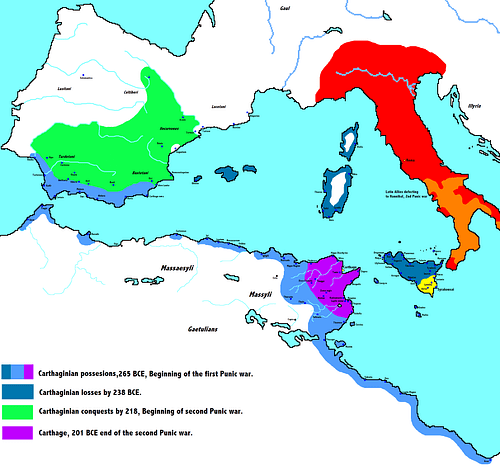

With an increase in revenue from the conquest of the peninsula, Rome was able to turn its focus further southward and across the Mediterranean Sea to the ancient Phoenician city of Carthage, and from 264 BCE to 146 BCE the two powers would fight a series of three wars – the so-called Punic Wars. Punic was the Roman name for Carthage. The wars began innocently enough when Rome was pulled into the affair by the Sicilian city of Messina, a city, together with neighboring Syracuse, soon to become its ally. The Romans disliked the presence of Carthage on the island, and when Rome reacted to Messina's appeal, war began. Carthage, likewise, resented Roman ambitions in Sicily and with the hopes of driving the “invaders” off the island began a series of raids along the Italian coast.

Since Rome was more of a land power - while Carthage was far more a naval power - the city quickly realized its limitations and began to build a large fleet of ships to counter the Carthaginian advantage. Wisely though, the Romans added a corvus or boarding ramp to each of their ships. The device enabled the Romans to pull alongside their opponent's ships, board them, and convert a sea battle to a land battle. After trading victories - Rome at Mylae and Carthage at Drepana - attempts to negotiate a treaty failed. Following further Roman victories, in 241 BCE Carthage sued for peace. Not only did the defeated city have to pay tribute, but Rome also gained the island of Sicily; this was its first province outside the peninsula. Rome would later seize the islands of Sardinia and Corsica.

The Second Punic War began as Carthage expanded its presence in Spain – something that would ultimately alarm the Roman Senate. An earlier treaty between Rome and Carthage had fixed a border between the two cities at the River Ebro, but an invasion of the city of Saguntum by Hannibal, son of the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca, would change this. Earlier, at the age of nine, Hannibal had promised his father that he would seek revenge against the Romans for the Carthaginian loss in the first war. Because of their focus on the Illyrians and Philip V, Rome initially failed to come to the aid of the city. Hannibal used it as a power base for further incursions throughout Spain and his eventual crossing of the Alps and into Roman territory in 218 BCE. This latter move finally pushed the city into action and a war began. Hannibal had accumulated a number of allies as he had crossed the mountains and onto the peninsula - especially the Roman-hating Gauls.

Hannibal and his army caused panic throughout Italy, but despite the Carthaginian threat, Rome's allies remained loyal and did not join Hannibal. However, although Hannibal achieved victory after victory, the general did not, for reasons unknown, attack the city of Rome. At the Battle of Cannae, the Romans would suffer one of their greatest defeats, but regardless of the loss, the legions would still not submit. Hannibal remained in Italy for over fifteen years. Under the leadership of Fabius Maximus, the Romans avoided further damaging conflicts by using a scorched earth policy —- raiding parties were used and crops were burned. Hannibal and his men grew desperate but heard little in the way of assistance from Carthage.

To best counter Hannibal the Romans decided it would not be wise to attack him head-on. Instead, the Senate sent Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio and his brother Publius to attack Carthaginian possessions in Spain. Fortunately, after both were killed in battle, Publius's son (also Publius Cornelius Scipio) reorganized the tattered army and introduced a shorter sword, the gladius, and a newer, better spear, the pilum. He gathered his forces together and attacked the enemy at Nova Carthago (New Carthage). Fearing that Rome might attack their city, the Carthaginian leaders recalled Hannibal from Italy in 204 BCE. Regrettably, Carthage suffered a resounding defeat at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE, although Hannibal was able to escape with his life and later to resume his vendetta against Rome in the Third Macedonian War when he allied with Antiochus III.

The wars would finally end between the two great cities in the Third Punic War when Rome attacked Carthage for a second time in 146 BCE. The end of the city came when the Roman senator Cato the Elder stood before the Senate and said "Carthago delenda est" or "Carthage must die." In response to this challenge, the city was razed, the land salted, and the people enslaved. The lands that had once belonged to Carthage - Spain and Northern Africa - were now part of the Roman Republic. Soon afterwards, Rome would add the provinces of Lusitania (modern-day Portugal) in 133 BCE and Southern Gaul in 121 BCE. Rome was in control of the entire western Mediterranean Sea.

Rome Looks to the East

Next, Rome turned its attention eastward towards the Balkans and Greece - a longing that would bring about the four Macedonian or Illyrian Wars. Rome had always admired the Hellenistic culture - the culture inspired by Alexander the Great. However, much of the Greek peninsula had been in turmoil since the death of Alexander and the Wars of Succession. And, when Philip V of Macedon (the former ally of Hannibal) began to expand his influence in Greece, then Rome, by invitation, entered into the fray. Rome had, of course, objected to the interference of the king after their loss at Cannae. Although the Roman Senate was reluctant to declare war, they recognized the seriousness of the Macedonian aggression. The Greeks, on the other hand, welcomed the Romans and their subsequent victory over Macedonian forces at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE. Afterwards, Greece fell under an umbrella of protection by Rome. Rome finally withdrew completely in 194 BCE, resorting to diplomacy instead of brute force.

Later, in 191 BCE Antiochus of Syria marched his army into Greece. His victory was short-lived, and he was defeated by Roman commander Lucius Cornelius Scipio at the Battle of Magnesia in 189 BCE. This battle would not end the fighting, for the war would later resume, but this time under the leadership of Philip's son, Perseus. The Third Macedonian War would end with his defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BCE. Finally, the conflicts would at long last end with the defeat of Antiochus IV and peace was finalized in 146 BCE, the same year as the Roman victory at Zama. After crushing several revolts throughout the peninsula, Rome was now in control of both the Balkans and Greece, and to demonstrate this, the city of Corinth was razed. Less than a decade later, Rome annexed Cilicia in Asia Minor and Cyrene in northern Africa.

Expanding West & Controlling the Mediterranean

From 219 BCE onward Rome had achieved dominance over the Mediterranean Sea - controlling parts of North Africa, Spain, Italy, and the Balkans. All of this brought great wealth to the Republic, and what remained soon came under their control. Pompey the Great would redraw the map in the eastern Mediterranean from the Black Sea to Syria and into Judea. Mithradates of Pontus posed a threat to the power of Rome in Asia Minor, attacking Roman provinces on the west coast of what is present-day Turkey - his death would bring both power to his son and peace with Rome. From 66 to 63 BCE Pompey marched from the Caucasus Mountains to the Red Sea. Many of the smaller kingdoms along the way became Roman client states or allies and all were obligated to supply reinforcements to the Roman army. Among these client states were Pontus, Cappadocia, Bithynia, Judea, Palestine, and, by 65 BCE, Armenia. In Africa Mauretania, Algeria, and Morocco also became client states.

While Pompey was occupied in the east, Julius Caesar fought the Gallic Wars, annexing all of Gaul, reportedly killing a million and enslaving another million to accomplish it. Despite the failed attempt to invade Britain, the northern borders of the Republic now extended to the banks of the Rhine and Danube. After his conquests to the north, the future “dictator for life” crossed the Rubicon and into Rome. After his assassination, his adopted son and successor, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium and - as a result Egypt became a Roman province. Augustus would become the new emperor, and the Empire was born, and with it, an era known as the Pax Romana or Roman peace emerged.

Maintaining The Empire

Despite the emperor's desire to expand the empire's borders further, its growth would come to an end in 9 CE in Germany when the commander Publius Quintilius Varus lost three Roman legions - ten percent of Rome's armed forces - at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest. Military victories were no longer about expansion and conquest but more defensive against internal and external forces such as riots, rebellions, and uprisings. Afterwards, there was limited expansion: Emperor Caligula (37-41 CE) tried to conquer Britain but failed while his uncle and successor Emperor Claudius (41-54 CE) actually accomplished it in 44 CE. Emperor Trajan (98-117 CE) annexed Dacia in 101 BCE and Mesopotamia a decade later. This would be the furthest east the empire had ever been or would ever be. Emperor Hadrian (117-138 CE) understood the need for “borders” and would relinquish the lands conquered by Trajan. Hadrian's Wall was built in northern England as a boundary between Britain and Scotland. To him and future emperors the empire needed borders - the empire now became one of pacification and Romanization, not conquest.

Splitting the Empire

The sheer size of the empire eventually became problematic - it was too large to manage and became more susceptible to barbaric invasions. In 284 CE a new emperor came to power. His name was Diocletian, and he understood the problems facing the empire. It had been under the watch for decades by poor leadership, so in order to restore unity, he divided the empire into a tetrarchy or rule of four. There was an emperor in the west - with Rome as its capital - and another emperor in the east - with his capital at Nicomedia (later Constantinople). After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, this eastern half would remain and become, in time, the Byzantine Empire.