Whether there was a king, a consul, or an emperor that stood supreme over Rome and its territories, the one constant throughout Roman history was the family. Like many earlier societies, the family was the fundamental social unit in the eternal city, and at its head was the father, or if there were no father, the eldest living male – the Latin expression for this is paterfamilias. One historian noted that the Roman family, in fact, reflected the principles that would shape Rome's Republican values.

Absolute Paternal Power

To a Roman male, his family was more than just his wife and children. It determined both his social standing and personal worth. His home or domus established his reputation, or his dignity (dignitas). Under Roman law, the father possessed absolute paternal power (patria potestas), not only over his wife and children but also his children's children and even his slaves, in fact, anyone who lived under his roof. After his father's death, Roman poet and statesman Cicero, the eldest son, bore responsibility for his brother and his brother's family. By law, a father could even beat his adult son (although this may have never been done). A father's lineage, his ancestry, was of the utmost importance, defining his position in the social hierarchy. A male's ties to his blood relatives - his children, parents, and siblings (cognati) were the strongest while the relatives acquired through marriage (his in-laws) or adfinitas, though still important, were secondary.

Marriages

Of course, there could be no family without marriage. Again, most marriages were not for love but were most commonly arranged for political, social or financial reasons. The great Roman commander Pompey married the daughter of Julius Caesar to cement their political relationship. Octavian (the future Augustus) married his sister Octavia to Mark Antony to solidify the Second Triumvirate. Augustus forced his stepson and heir, the future Emperor Tiberius, to divorce his wife Vipsania in order to marry the emperor's daughter Julia in an attempt to solidify the young man's ascent to the throne. Unfortunately, a woman had little say in whom she married. Often the marriage would be to a much older man - something that later left many a young bride a widow. A girl was usually married or was betrothed between the ages of 12 to 15, sometimes as early as 11, although there is no mention as to when the marriage was consummated.

The state played little or no part in a marriage. Most were simple and private affairs while others were far more elaborate and expensive. Basically, a couple was married if they claimed to be and divorced if they said so. A celebration party might or might not follow. Of course, the bride's father had to provide a dowry, however, the husband was obligated to return it if the marriage ended in a divorce. Unlike today, there didn't have to be a specific reason for a divorce. Cicero, after several years of being married to his wife Terentia, simply ended it in 46 BCE without any reason – a process known as affectio maritalis. He married shortly afterwards to a much younger woman only to have it end in divorce, too. In 58 BCE, while Cicero was away from Rome in Thessalonica and going through a personal crisis, he wrote to his wife a very moving, personal letter.

Many people write to me and everybody tells me how unbelievably brave and strong you are, Terentia, and about how you are refusing to allow your troubles either of mind or of body to exhaust you. How unhappy it makes me that you with your courage, loyalty, honesty, and kindness should have suffered all these miseries because of me! (Grant, 65)

There were, however, marriages with a more elaborate and costly ceremony, complete with a priest and marriage contract. First, an animal would be sacrificed and its entrails read to see if the gods approved. The wedding, June was always a popular month, took place in the atrium of the bride's home. She typically wore a tunic-style dress (tunica recta), which was usually yellow. After a ring was placed on the third finger of her left hand and the matron of honor joined the couple's hands, a contract was signed. Next, a procession was led to the groom's home where festivities would last for several days. The bride was even carried over the threshold. Of course, the groom paid for the reception - complete with food, dancing, and songs.

Women's Status

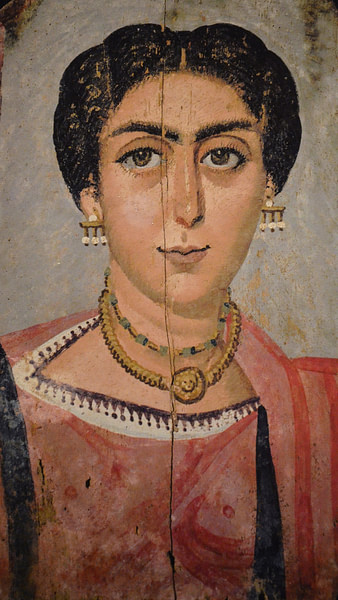

It is evident that women were not generally held in high regard in Rome. They were married at an early age to a man they may or may not have loved. There were very few, if any, unmarried women. Although they could inherit property from their father's estate, they had little in the way of identity, indeed most were almost nameless. While considered by law to be citizens, they could not hold public office or vote. The control of their very being was handed over from their father to their new husband. Although no examples exist, a husband could, by law, even execute his wife for adultery.

However, unlike women in ancient Greece and women in Near Eastern societies, a woman in Rome could appear with her husband in public – although public displays of affection were forbidden. She could attend the theater (albeit in the back rows) and use the public Roman baths (separately, of course, from the men). The role of women in the Roman world was to provide children and to be head of the household, for which role she held the keys to the house. She oversaw cooking and clothing production – both spinning and weaving – as well as supervised domestic servants. She controlled the economic affairs of the home and, if necessary, helped in her husband's shop. A wife could even dine at the same table with her husband. Much later, as the role of a woman changed over time, she could become a pharmacist, a baker, and even a doctor.

Oddly, Roman women did not have a first name or praenomen like their male counterparts. Their name came from the father's middle name or nomen gentilicium. For example, the daughter of Cicero's name Tullia came from his middle name of Tullius while Caesar's daughter was Julia derived from Julius, as his birth name was actually Gaius Julius Caesar. Elder women and their daughters with the same name used both major and minor, or prima and secunda, to distinguish them.

Children's Status

The real purpose of marriage, aside from the political one, was to produce children and heirs. Regrettably, childbirth in ancient Rome was the biggest cause of death for young women. Although sources vary, over one-third of the children born to a Roman family died before his or her first birthday. If a woman could not have children, it was considered her fault. Something that may seem odd to today's parent but a Roman mother was taught not to grieve but to take a child's death calmly. Almost one-half of children would not survive to the age of five. If one survived to the age of ten, he or she had a life expectancy to live at least another 40-50 years. The causes of a child's early death were many – dysentery, diarrhea, cholera, typhoid fever, malaria, pneumonia, and tuberculosis were just some of the causes. Added to these risks of childhood in ancient Rome were poor nutrition, poor hygiene, and the city's cramped living quarters.

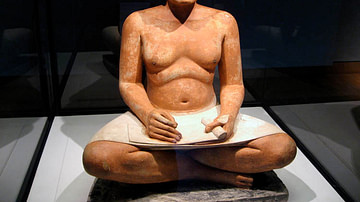

Unlike our present day where adult children often will leave the nest, in Rome, several generations could easily live under one roof, and even then an adult, married male and his family were accountable to the father. This unconditional authority allowed the father to not only arrange marriages for his children but also determine whether infants (especially females) were accepted or allowed to die. As in ancient Sparta, it was not uncommon for weak, disabled, or unwanted children to be left exposed to the elements. Girls, particularly in poorer families, were especially unwanted because of the need to provide a dowry at their marriage. In more affluent families children, both boys and girls, were usually educated in the basics at home (the responsibility of the mother), often by a private tutor (who was usually Greek). Some male children would attend a secondary school or grammaticus at the Roman Forum and then travel to such places as Athens to receive further schooling in rhetoric and philosophy.

A child's citizenship, in particular a male's, was not a birthright. A father could easily reject a child at birth. Tradition dictated that he had to take the newborn into his arms in order for him or her to be accepted. If not, if he rejected the child, a slave would leave the infant by the roadside. The Romans were a superstitious people, and it was customary for a father to wait at least nine days before a male child would be named. They believed that by nine days all evil spirits would be gone. The future of a child could be read simply through the behavior of passing birds. A charm or bulla was placed around a male child's neck for good luck until he came of age (usually 14) when he would don a toga and be taken to the Forum and registered as a citizen.

Conclusion

Roman society, then, centered on the family and emphasized the role of the father. Much later the absolute power of the father would weaken as many of the more traditional social norms would be challenged and broken down. Unlike their counterparts elsewhere, women in ancient Rome would gain a modicum of independence and their children, or at least the wealthier ones, became free to marry whomever they wished. In the latter days of the Roman Republic, many public figures – one of the more notable was Cicero – claimed that the decline in Roman morality and loss of the old established values was a reason for its fall.

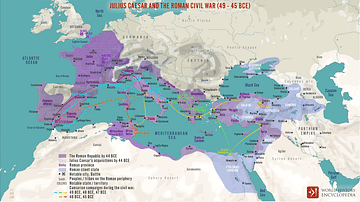

In 18 BCE, Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), objected to this decline of Roman morals and enacted a series of laws to promote marriage, marriage fidelity, and childbirth. However, with the reforms of Augustus, the idea of paterfamilias would expand – he became pater patriae, or father of his country. This was not the first time this term had been used, for Cicero had received the title after his prosecution of Catiline, and Caesar received it after his victory at the Battle of Munda. Many future emperors would embrace this concept, that is, the idea of being a father to the people. The idea of a male-dominated society would, of course, not end with the fall of the Western Roman Empire. It would remain in many areas and cultures well into the modern era.