The Greek historian Herodotus provides an accurate description of the devotion of the ancient Egyptians to cats in Book II of his Histories, but this passage is often cited out of context. Chapters II.66-67 are frequently anthologized without the preceding passage discussing how the Egyptians valued all animals and regarded them as sacred.

Although he makes clear in II.65 that he does not want to deal with the subject of the gods as related to animals, he then relates how carefully humans tend to their animals' needs as a reflection of Egyptian religion. To the ancient Egyptians, animals – like everything else around them – were a gift from the gods, and it was their responsibility to value and care for all such gifts.

In citing only chapters II.66-67, authors and editors inadvertently give the false impression that only cats were held in such high regard when, actually, all animals were. The cat was among the most popular pets in ancient Egypt, but not the only one the Egyptians valued, and Herodotus makes this clear when his earlier chapter on animals is cited along with the passages on cats.

Herodotus actually deals with a wide array of animals throughout his work, including those in Egypt. Scholar Colin MacCormack notes:

Among ancient historical works, Herodotus' Histories stand out in the unusually large amount of space dedicated to discussions of animals. Whereas only 42 animal references occur in Thucydides, Herodotus furnishes readers with a massive 804 references to at least 111 different animal terms. (1)

After his passage on cats, in fact, Herodotus goes on to discuss the crocodile, hippo, otter, birds, and snakes at much greater length. Even so, as the cat seems to have been one of the most popular – and is most recognizable as a domesticated pet in the modern age – his discussion of the cat has become the most well-known.

This is hardly surprising considering the cats' association with ancient Egypt. Even the English word cat is derived from Egypt as it comes from their name for the animal, quattah, which gives Greek its word gata and this then influenced the word for cat in other languages up to the present day: Spanish gato, French chat, and German Katze among them. This is also true for the term 'pussy' as in 'pussycat' which comes from the Egyptian name for the goddess of cats, Bastet, Pasht.

Even so, as noted, his famous passage on Egyptians rescuing cats from burning buildings loses some of its meaning when cited out of context. The cats in the passage are not being saved only because they were favored pets and not only because of the Egyptian reverence for life, but because of their association with Bastet.

Cats in Egypt & Herodotus' Description

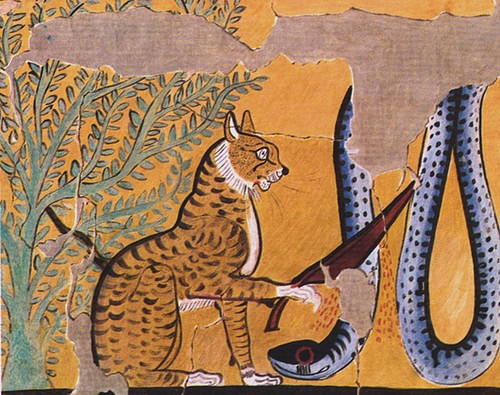

Cats had a long and illustrious association with divinity in ancient Egypt between c. 3150-30 BCE. The feline goddess Mafdet appears in the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150 to c. 2890 BCE) as a protector and embodiment of the concept of justice. She was considered especially potent in protecting against attacks by scorpions and snakes and was among the deities who safeguarded the sun god Ra on his nightly journey through the underworld from the threat of the great serpent Apophis and was, therefore, one of the principal deities who ensured the sun rose each morning.

Mafdet was especially popular during the reign of Den (c. 2990-2940 BCE), considered the greatest king of the First Dynasty, and was the protector of his personal chambers. She remained an important goddess through the period of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 to c. 1069 BCE) though her responsibilities were taken on by the goddesses Serket (also given as Selket, who protected against venomous bites) and Bastet, one of the most popular goddesses in Egyptian mythology.

Bastet was the goddess of the home, domesticity, fertility, childbirth, women's secrets, and cats. Whereas Mafdet was depicted as a cat with the skin of a cheetah, Bastet is commonly pictured as either a cat or a woman with the head of a cat. Bastet ensured the safety of one's home and the health of women and children by warding off evil spirits and disease and so was widely venerated by both sexes. Her cult center at Bubastis was one of the richest in the country, and as Herodotus notes below, people from all over traveled to the city to have their dead cats interred there, close to the goddess.

Bastet took over the duties of Mafdet during the Second Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2890 to c. 2670 BCE) and remained popular until the end of the Ptolemaic Dynasty in 30 BCE. As with all the deities of ancient Egypt, Bastet maintained the value of ma'at (harmony, balance), and Herodotus touches on this in II.66 in his discussion of male cats killing kittens in order to mate. Although this passage is sometimes interpreted as critical of the male cats' behavior, it is actually discussing natural population regulation. As he suggests, without the intervention of the males, the cat population would soar out of control. To the Egyptians, the males' behavior would have been approved by Bastet in the interests of balance.

The best-known passage on cats and burning homes also relates to Bastet as she was the goddess and protector of cats. Herodotus' description of the Egyptians focusing on rescuing the cats is not just relating how someone might behave in trying to save a beloved pet but has to do with honoring the goddess. Although Bastet was understood as a home's protector, there could be many reasons why it caught fire – one had sinned against some other god, had not observed proper funerary rites, or had lapsed in another way – and so justice was served in the burning of the house.

If one wanted Bastet to continue her protection of one's new home, it was in one's best interest to rescue her cats since she could be as vengeful as she was benevolent. Scholar Geraldine Pinch notes:

Bastet has a double aspect of nurturing mother and terrifying avenger. It is the demonic aspect that mainly features in the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead and in medical spells. The "slaughterers of Bastet" were said to inflict plague and other disasters on humanity. One spell advises pretending to be the 'son of Bastet' in order to avoid caching the plague. (115)

Bastet, like Mafdet, was linked with the concept of justice and, in this capacity was known as the Lady of Dread and the Lady of Slaughter for her swift response to any wrongdoing. Recognizing how vengeful Bastet could be when she felt wronged, the Egyptians naturally sought to save her cats without bothering to address the burning home.

These passages on cats are given context by chapter II.65 on how Egyptians cared for all animals. The rescue of cats from fires correlates directly to the value Egyptians placed on all life and, within that perspective, how cats were valued specifically. Even though wild animals were killed on the hunt, fish were caught for food, and some animals were offered in sacrifice, all were regarded as sacred gifts, not only the cat.

The Text

The following passages are taken from Herodotus: The Histories by Robin Waterfield:

II.65 All the animals in Egypt are regarded as sacred. Some are domesticated, and others are not, but if I were to explain why some animals are allowed to roam free, as sacred creatures, my account would be bound to discuss issues pertaining to the gods, and I am doing my best to avoid relating such things. It is only when I have had no choice that I have touched on them already. However, one of their customs concerning animals is as follows. Each separate species of animal has been appointed a keeper who is in charge of looking after it; the keeper may be an Egyptian man or woman, and children inherit the post from their parents. In cities, people fulfil their vows by praying to the god whose sacred creature a given type of animal is, and shaving their child's head (it might be the whole head, or a half, or a third) and weighing the hair in a pair of scales against some silver. This weight in silver is then given to the keeper of the animals. She cuts up as much fish as the silver buys and gives it as food to the animals. This is how the animals are fed. The deliberate killing of one of these animals is punishable by death, and anyone who kills one of them accidentally has to pay a fine whose amount is determined by the priests. However, the death of an ibis or hawk at someone's hands, whether or not he intended to kill it, is inevitably a capital offense.

II.66 Although there are plenty of domestic animals in Egypt, there would be many more if it were not for what happens to the cats. When female cats give birth, they stop having intercourse with the males. However much the toms want to mate with them, they are unable to do so. The toms have therefore come up with a clever solution. They sneak in and steal the kittens away from their mothers, and then kill them (but not for food). The females, deprived of their young, long to have some more, because the feline species is very fond of its young, and so they go to the males.

If a house catches fire, what happens to the cats is quite extraordinary. The Egyptians do not bother to try to put the fire out, but position themselves at intervals around the house and look out for the cats. The cats slip between them, however, and even jump over them, and dash into the fire. This plunges the Egyptians into deep grief. In households where a cat dies a natural death, all the people living there shave off their eyebrows – nothing more. In households where a dog dies, they shave their whole bodies, head and all.

II.67 After their death, the cats are taken to sacred chambers in the city of Bubastis where they are mummified and buried. Dogs are buried by each householder in his own community in sanctified tombs, and mongooses receive the same form of burial as well. Shews and hawks are taken to the city of Buto, and ibises to Hermepolis. Bears (which are rare) and wolves (which are not much larger than foxes) are buried wherever they are found lying.

Conclusion

Herodotus' description of animals in ancient Egypt, and cats specifically, exemplifies his overall approach to history as he focuses on the details that characterize a culture. He does not always comment on the full significance of an event, policy, or practice but suggests it is indicative of the values of the civilization under consideration and, as MacCormack observes, is frequently quite 'modern' in his approach:

Herodotus alone points to behavior as influencing population. According to him, without the habit of male cats killing kittens (2.66) or of baby vipers killing their mothers (3.108), both populations would explode in number. He attributes this natural self-regulation to a divine insight overseeing the world…More generally, unlike the macroscopic speculations on cosmology or matter of the natural philosophers, Herodotus instead prefers observation on mundane subjects such as geology, flora and fauna. Aside from its modernity, these zoological investigations also reveal an underlying methodology: the interconnectivity of humans and their environment. (2)

Herodotus' passages on cats are among the best-known from his Histories and are frequently cited in referencing the value Egyptians placed on cats. The passages have a much deeper meaning, however, as MacCormack notes, which is understood clearly when given the context of II.65. The Egyptians cared for all animals in recognition of the importance of balance – "the interconnectivity of humans and their environment" – and understood that, what was good for the animals, was ultimately also best for themselves.