Buddhism is a non-theistic religion (no belief in a creator god), also considered a philosophy and a moral discipline, originating in the region of modern-day India in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. It was founded by the sage Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE) who, according to legend, had been a Hindu prince.

Before abandoning his position and wealth to become a spiritual ascetic, Siddhartha lived comfortably as a noble with his wife and family but once he became aware of human suffering he felt he had to find some way of easing people's pain. He pursued strict spiritual disciplines to become an enlightened being who taught others the means by which they could escape samsara, the cycle of suffering, rebirth, and death.

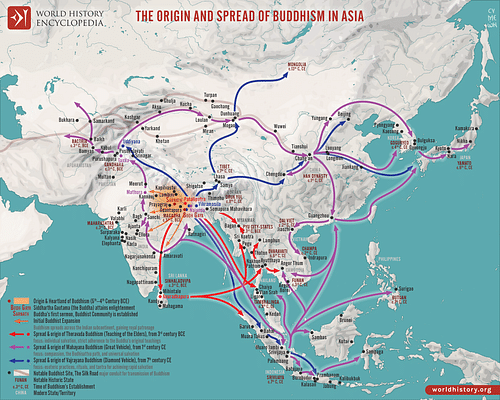

The Buddha developed the belief system at a time when Ancient India was in the midst of significant religious and philosophical reform. Buddhism was, initially, only one of many schools of thought which developed in response to what was perceived as the failure of orthodox Hinduism to address the needs of the people. It remained a relatively minor school until the reign of Ashoka the Great (268-232 BCE) of the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE) who embraced and spread the belief, not only throughout India, but through Central and Southeast Asia.

Buddhism's central vision can be summed up in four verses from one of its central sacred texts, the Dhammapada:

Our life is shaped by our mind; we become what we think. Suffering follows an evil thought as the wheels of a cart follow the oxen that draw it.

Our life is shaped by our mind; we become what we think. Joy follows a pure thought like a shadow that never leaves. (I.1-2)

From desire comes grief, from desire comes fear; one who is free from desire knows neither grief nor fear.

Attachment to objects of desire brings grief, attachment to objects of desire brings fear; one who is free of attachment knows neither grief nor fear. (XVI.212-213)

The Buddha came to understand that desire and attachment caused suffering and humans suffered because they were ignorant of the true nature of existence. People insisted on permanent states in life and resisted change, clung to what they knew, and mourned what they lost. In his quest for a means to live without suffering, he recognized that life is constant change, nothing is permanent, but one could find inner peace through a spiritual discipline that recognized beauty in the transience of life while also preventing one from becoming ensnared by attachment to impermanent objects, people, and situations. His teaching centers on the Four Noble Truths, the Wheel of Becoming, and the Eightfold Path to form the foundation of Buddhist thought and these remain central to the different schools of Buddhism which continue in the modern day.

Historical Background

Hinduism (Sanatan Dharma, “Eternal Order”) was the dominant faith in the region of modern-day India in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE when a wave of religious and philosophical reform swept the land. Scholar John M. Koller notes how, “a major social transformation from agrarian life to urban trade and manufacture was underway, leading to a questioning of the old values, ideas, and institutions” (46). Hinduism was based on acceptance of the scriptures known as the Vedas, thought to be eternal emanations from the universe which had been “heard” by sages at a certain time in the past but were not created by human beings.

The Vedas were “received” and recited by the Hindu priests in Sanskrit, a language the people did not understand, and various philosophical thinkers of the time began to question this practice and the validity of the belief structure. Many different schools of philosophy are said to have developed at this time (most of which did not survive), which either accepted or rejected the authority of the Vedas. Those which accepted the orthodox Hindu view and the resulting practices were known as astika (“there exists”) and those which rejected the orthodox view were known as nastika (“there does not exist”). Three of the nastika schools of thought to survive this period were Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Hinduism held the universe was governed by a supreme being known as Brahman who was the Universe itself and it was this being who had imparted the Vedas to humanity. The purpose of one's life was to live in accordance with the divine order as it had been set down and perform one's dharma (duty) with the proper karma (action) in order to eventually find release from the cycle of rebirth and death (samsara) at which point the individual soul would attain union with the oversoul (atman) and experience complete liberation and peace.

Charvaka rejected this belief and offered materialism instead. Its founder, Brhaspati (l. c. 600 BCE) claimed it was ridiculous for people to accept the word of Hindu priests that an incomprehensible language was the word of God. He established a school based on direct perception in ascertaining truth and the pursuit of pleasure as the highest goal in life. Mahavira (also known as Vardhamana, l. c. 599-527 BCE) preached Jainism based on the belief that individual discipline and strict adherence to a moral code led to a better life and release from samsara at death. The Buddha recognized that both of these paths represented extremes and found what he called a “middle way” between them.

Siddhartha Gautama

According to Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha Gautama was born in Lumbini (modern-day Nepal) and grew up, the son of a king. After a seer predicted he would either become a great king, or spiritual leader if he were to witness suffering or death, his father shielded from any of the harsh realities of existence. He married, had a son, and was groomed to succeed his father as king. One day, however (or, in some versions, over a succession of days), his coachman drove him out of the compound where he had spent his first 29 years and he encountered what are known as the Four Signs:

- An aged man

- A sick man

- A dead man

- An ascetic

With the first three, he asked his driver, “Am I, too, subject to this?”, and the coachman assured him that everyone aged, everyone grew sick at one point or another, and everyone died. Siddhartha became upset as he understood that everyone he loved, all his fine things, would be lost and that he, himself, would one day be as well.

When he saw the ascetic, a shaven-headed man in a yellow robe, smiling by the side of the road, he asked why he was not like other men. The ascetic explained he was pursuing a peaceful life of reflection, compassion, and non-attachment. Shortly after this encounter, Siddhartha left his wealth, position, and family to follow the ascetic's example.

He at first sought out a famous teacher from whom he learned meditation techniques, but these did not free him from worry or suffering. A second teacher taught him how to suppress his desires and suspend awareness, but this was no solution either as it was not a permanent state of mind. He tried to live as the other ascetics lived, practicing what was most likely Jain discipline, but even this was not enough for him. At last, he decided to refuse the needs of the body by starving himself, eating only a grain of rice a day, until he was so emaciated that he was unrecognizable.

According to one version of the legend, at this point, he either stumbled into a river and received a revelation of the middle way. In the other version of the story, a milkmaid named Sujata comes upon him in the woods near her village and offers him some rice milk, which he accepts, and so ends his period of strict asceticism as he glimpses the idea of a “middle way”. He goes and sits beneath a Bodhi tree, on a bed of grass, in the nearby village of Bodh Gaya, vowing he will either come to understand how best to live in the world or will die.

He understood, in a flash of illumination, that humans suffered because they insisted on permanence in a world of constant change. People maintained an identity which they called their “self” and which would not change, maintained clothing and objects they thought of as “theirs”, and maintained relationships with others which they believed would last forever – but none of this was true; the nature of life, all of life, was change and the way to escape suffering was to recognize this and act on it. At this moment he became the Buddha (“awakened one” or “enlightened one”) and was freed from ignorance and illusion.

Having attained complete enlightenment, recognizing the interdependent and transient nature of all things, he recognized that he could now live however he pleased without suffering and could do whatever he wanted. He hesitated to teach what he had learned to others because he felt they would just reject him but was finally convinced that he had to try and so preached his first sermon at the Deer Park in Sarnath at which he first described the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path which led one from illusion and suffering to enlightenment and joy.

It should be noted that this story of the Buddha's journey from illusion to awareness was later tailored to him following the establishment of the belief system and may, or may not, reflect the reality of Buddha's early life and awakening. Scholars Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. note that early Buddhists were “motivated in part by the need to demonstrate that what the Buddha taught was not the innovation of an individual, but rather the rediscovery of a timeless truth” in order to give the belief system the same claim to ancient, divine origins held by Hinduism and Jainism (149). Buswell and Lopez continue:

Thus, in their biographies, all of the buddhas of the past and future are portrayed as doing many of the same things. They all sit cross-legged in their mother's womb; they are all born in the “middle country” of the continent; immediately after their birth, they all take seven steps to the north; they all renounce the world after seeing the four sights and after the birth of a son; they all achieve enlightenment seated on a bed of grass. (149)

However this may be, the legend of Siddhartha's journey and spiritual awakening became well known in oral tradition and was alluded to or included in written works from around 100 years after his death through the 3rd century CE when it appears in full in the Lalitavistara Sutra. The story has been repeated since and, lacking an alternative, is accepted as true by the majority of Buddhists.

Teachings & Beliefs

As noted, what started Siddhartha on his quest was the realization that he would lose everything that he loved, and this would cause him suffering. From this realization, he understood that life was suffering. One suffered at birth (as did one's mother) and suffered then throughout one's life by craving what one did not have, fearing for the loss of what one did have, mourning the loss of what one once had, and finally dying and losing everything only to be reincarnated to repeat the process.

In order for life to be anything other than suffering, one had to find a way to live it without the desire to possess and hold it in a fixed form; one had to let go of the things of life while still being able to appreciate them for the value they had. After attaining enlightenment, he phrased his belief on the nature of life in his Four Noble Truths:

- Life is suffering

- The cause of suffering is craving

- The end of suffering comes with an end to craving

- There is a path which leads one away from craving and suffering

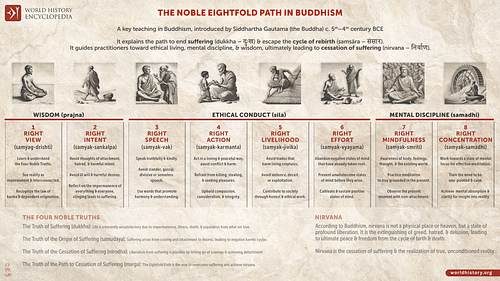

The four truths are called “noble” from the original arya meaning the same but also “worthy of respect” and suggesting “worth heeding”. The path alluded to in the fourth of the truths is The Eightfold Path which serves as a guide to live one's life without the kind of attachment that guarantees suffering:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

As Koller points out, the first three have to do with wisdom, the next two with conduct, and the last three with mental discipline. He continues:

The Noble Eightfold Path should not be thought of as a set of eight sequential steps, with perfection at one step required before advancing to the next. Rather, these eight components of the path should be thought of as guiding norms of right living that should be followed more or less simultaneously, for the aim of the path is to achieve a completely integrated life of the highest order…Wisdom is seeing things as they really are, as interrelated and constantly changing processes…moral conduct is to purify one's motives, speech, and action, thereby stopping the inflow of additional cravings…mental discipline works to attain insight and to eliminate the bad dispositions and habits built up on the basis of past ignorance and craving. (58)

By recognizing the Four Noble Truths and following the precepts of the Eightfold Path, one is freed from the Wheel of Becoming which is a symbolic illustration of existence. In the hub of the wheel sit ignorance, craving, and aversion which drive it. Between the hub and the rim of the wheel are six states of existence: human, animal, ghosts, demons, deities, and hell-beings. Along the rim of the wheel are depicted the conditions which cause suffering: birth, body-mind, consciousness, contact, feeling, thirst, grasping, volition, and so on.

By recognizing that these conditions cause suffering one can avoid it by disciplining one's self through the Eightfold Path so that one is no longer driven by ignorance, craving, and aversion and is free of the wheel of samsara which binds one to continual rebirth, suffering, and death. In adhering to this discipline, one could live in one's life but not be controlled and suffer by one's attachment to the things of that life and, when one died, one was not reborn but attained the liberation of the spiritual state of nirvana. This, then, is the “middle way” Buddha found between slavish attachment to material goods and personal relationships and the extreme asceticism practiced by the Jains of his time.

He called his teachings the Dharma which, in this case, means “cosmic law” as opposed to Hinduism which defines the same term as “duty”. One could, however, interpret Buddha's Dharma as “duty” in that he believed one had a duty to one's self to take responsibility for one's life, that each individual was finally responsible for how much they wanted to suffer – or not, and that everyone, finally, could be in control of their lives. He discounted a belief in a creator god as irrelevant to the lives of human beings and a contributor to suffering in that one cannot possibly know God's will and believing that one can only leads to frustration, disappointment, and pain. No god is required in order to follow the Eightfold Path; all one needs is the commitment to taking full responsibility for one's own actions and their consequences.

Schools & Practices

Buddha continued preaching his Dharma for the rest of his 80 years, finally dying at Kushinagar. He told his disciples that, after his death, they should have no leader and he did not want to be venerated in any way. He requested his remains be interred in a stupa and placed at a crossroads. This did not come to pass, however, since his followers had their own ideas, and so his remains were deposited in eight (or ten) stupas in different regions corresponding to important events in his life. They also chose a leader as they wished to continue his work and so, as humans do, held councils and debates and initiated rules and regulations.

At the First Council in c. 400 BCE, the core teachings and monastic discipline were decided upon and codified. At the Second Council in 383 BCE, a dispute over proscriptions in monastic discipline led to the first schism between the Sthaviravada school (which argued for observing said proscriptions) and the Mahasanghika school ("Great Congregation") which represented the majority and rejected them. This schism would eventually result in the establishment of three different schools of thought:

- Theravada Buddhism (The School of the Elders)

- Mahayana Buddhism (The Great Vehicle)

- Vajrayana Buddhism (The Way of the Diamond)

Theravada Buddhism (referred to as Hinayana “little vehicle” by Mahayana Buddhists, considered a pejorative term by the Theravada) claims to practice the belief as it was originally taught by Buddha. Adherents follow the teachings in the Pali language and focus on becoming an arhat (“saint”). This school is characterized by a focus on individual enlightenment.

Mahayana Buddhism (which includes Zen Buddhism) follows the teachings in Sanskrit and adherents work toward becoming a Bodhisattva (“essence of enlightenment”), one who, like Buddha, has attained full awareness but puts off the peace of nirvana in order to help others shed their ignorance. Mahayana Buddhism is the most popular form practiced today and also claims to follow the Buddha's teachings faithfully.

Vajrayana Buddhism (also known as Tibetan Buddhism) dispenses with the concept of having to commit to Buddhist discipline and change one's lifestyle in order to begin a Buddhist walk on the Eightfold Path. This school advocates the belief illustrated by the phrase Tat Tvam Asi (“thou art that”) that one already is a Bodhisattva, one only has to realize it. One need not, therefore, give up unhealthy attachments at the start of one's walk but, rather, just proceed along the path and those attachments will become less and less alluring. As with the others, Vajrayana also claims it is the most faithful to the Buddha's original vision.

All three schools adhere to the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, as do the many other minor schools, and none is objectively considered more legitimate than the others though, obviously, adherents of each would disagree.

Conclusion

Buddhism continued as a minor philosophical school of thought in India until the reign of Ashoka the Great who, after the Kalinga War (c. 260 BCE), renounced violence and embraced Buddhism. Ashoka spread the Dharma of the Buddha throughout India under the name dhamma which equates to “mercy, charity, truthfulness, and purity” (Keay, 95). He had the Buddha's remains disinterred and reinterred in 84,000 stupas all through the country along with edicts encouraging the Buddhist vision. He also sent missionaries to other countries – Sri Lanka, China, Thailand, Greece among them – to spread Buddha's message.

Buddhism became more popular in Sri Lanka and China than it had ever been in India and spread further from temples established in these countries. Buddhist art began appearing in both countries between the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, including anthropomorphic depictions of Buddha himself. Earlier artists, during Ashoka's time, had refrained from depicting Buddha and only suggested his presence through symbols but, increasingly, Buddhist sites included statues and images of him, a practice first initiated by a sect of the Mahasanghika school.

In time, these statues became objects of veneration. Buddhists do not “worship” the Buddha but, at the same time, they do in that the statue representing Buddha becomes not only a focal point for concentration on one's own path to enlightenment but a way of expressing gratitude to the Buddha. Further, one who becomes a Buddha (and, according to Mahayana Buddhism, anyone can) does become a kind of “god” in that they have transcended the human condition and so deserve special recognition for that accomplishment. In the present day, there are over 500 million practicing Buddhists in the world, each following his or her own understanding of the Eightfold Path and continuing to spread the message that one only has to suffer in life as much as one wants to and there is a way which leads to peace.