Siddhartha Gautama (better known as the Buddha, l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE) was, according to legend, a Hindu prince who renounced his position and wealth to seek enlightenment as a spiritual ascetic, attained his goal and, in preaching his path to others, founded Buddhism in India in the 6th-5th centuries BCE.

The events of his life are largely legendary, but he is considered an actual historical figure and a younger contemporary of Mahavira (also known as Vardhamana, l. c. 599-527 BCE) who established the tenets of Jainism shortly before Siddhartha's time.

According to Buddhist texts, a prophecy was given at Siddhartha's birth that he would become either a powerful king or great spiritual leader. His father, fearing he would become the latter if he were exposed to the suffering of the world, protected him from seeing or experiencing anything unpleasant or upsetting for the first 29 years of his life. One day (or over the course of a few) he slipped through his father's defenses and saw what Buddhists refer to as the Four Signs:

- An aged man

- A sick man

- A dead man

- A religious ascetic

Through these signs, he realized that he, too, could become sick, would grow old, would die, and would lose everything he loved. He understood that the life he was living guaranteed he would suffer and, further, that all of life was essentially defined by suffering from want or loss. He therefore followed the example of the religious ascetic, tried different teachers and disciplines, and finally attained enlightenment through his own means and became known as the Buddha (“awakened” or “enlightened” one).

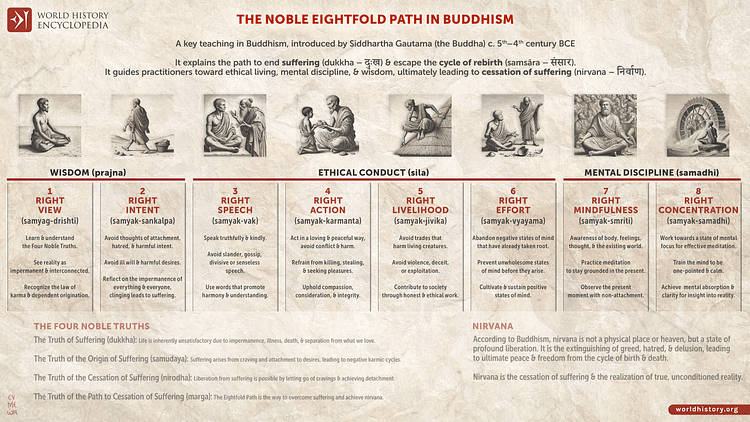

Afterwards, he preached his “middle way” of detachment from sense objects and renunciation of ignorance and illusion through his Four Noble Truths, the Wheel of Becoming, and the Eightfold Path to enlightenment. After his death, his disciples preserved and developed his teachings until they were spread from India to other countries by the Mauryan king Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE). From the time of Ashoka on, Buddhism has continued to flourish and, presently, is one of the major world religions.

Historical Background

Siddhartha was born in Lumbini (in modern-day Nepal) during a time of social and religious transformation. The dominant religion in India at the time was Hinduism (Sanatan Dharma, “Eternal Order”) but a number of thinkers of the period had begun to question its validity and the authority of the Vedas (the Hindu scriptures) as well as the practices of the priests.

On a practical level, critics of orthodox Hinduism claimed that the religion was not meeting the needs of the people. The Vedas were said to have been received directly from the universe and could not be questioned, but these scriptures were all in Sanskrit, a language the people could not understand, and were interpreted by the priests to encourage acceptance of one's place in life – no matter how difficult or impoverished – while they themselves continued to live well from temple donations.

On a theological level, people began to question the entire construct of Hinduism. Hinduism taught that there was a supreme being, Brahman, who had not only created the universe but was the universe itself. Brahman had established the divine order, maintained this order, and had delivered the Vedas to enable human beings to participate in this order with understanding and clarity.

It was understood that the human soul was immortal and that the goal of life was to perform one's karma (action) in accordance with one's dharma (duty) in order to break free from the cycle of rebirth and death (samsara) and attain union with the oversoul (atman). It was also understood that the soul would be incarnated in physical bodies multiple times, over and over, until one finally attained this liberation.

The Hindu priests of the time defended the faith, which included the caste system, as part of the divine order but, as new ideas began to circulate, more people questioned whether that order was divine at all when all it seemed to offer was endless rounds of suffering. Scholar John M. Koller comments:

From a religious perspective, new ways of faith and practice challenged the established Vedic religion. The main concern dominating religious thought and practice at the time of the Buddha was the problem of suffering and death. Fear of death was an especially acute problem, because death was seen as an unending series of deaths and rebirths. Although the Buddha's solution to the problem was unique, most religious seekers at this time were engaged in the search for a way to obtain freedom from suffering and repeated death. (46)

Many schools of thought arose at this time in response to this need. Those which supported orthodox Hindu thought were known as astika (“there exists”), and those which rejected the Vedas and the Hindu construct were known as nastika (“there does not exist”). Among the nastika schools which survived the time and developed were Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Early Life & Renunciation

Siddhartha Gautama grew up in this time of transition and reform but, according to the famous Buddhist legend concerning his youth, would not have been aware of any of it. When he was born, it was prophesied that he would become a great king or spiritual leader and his father, hoping for the former, hid his son away from anything that might be distressing. Siddhartha's mother died within a week of his birth, but he had no awareness of this, and his father did not want him to experience anything else as he grew which might inspire him to adopt a spiritual path.

Siddhartha lived among the luxuries of the palace, was married, had a son, and lacked for nothing as the heir-apparent of his father until his experience with the Four Signs. Whether he saw the aged man, sick man, dead man, and ascetic in rapid succession on a single ride in his carriage (or chariot, depending on the version), or over four days, the story relates how, with each one of the first three, he asked his driver, “Am I, too, subject to this?” His coachman responded, telling him how everyone aged, everyone was subject to illness, and everyone died.

Reflecting upon this, Siddhartha understood that everyone he loved, every fine object, all his grand clothes, his horses, his jewels would one day be lost to him – could be lost to him at any time on any day – because he was subject to age, illness, and death just like everyone else. The idea of such tremendous loss was unbearable to him but, he noticed, the religious ascetic – just as doomed as anyone – seemed at peace and so asked him why he seemed so content. The ascetic told him he was pursuing the path of spiritual reflection and detachment, recognizing the world and its trappings as illusion, and was therefore unconcerned with loss as he had already given everything away.

Siddhartha knew that his father would never allow him to follow this path and, further, he had a wife and son he was responsible for who would also try to prevent him. At the same time, though, the thought of accepting a life he knew he would ultimately lose and suffer for was unbearable. One night, after looking at all of the precious objects he was attached to and his sleeping wife and son, he walked out of the palace, left his fine clothes, put on the robes of an ascetic, and departed for the woods. In some versions of the story, he is assisted by supernatural means while, in others, he simply leaves.

Criticism of the Four Signs Tale

Criticism of this story often includes the objection that Siddhartha could not possibly have gone 29 years without ever becoming sick, seeing an older person, or being aware of death, but this is explained by scholars in two ways:

- the story is symbolic of the conditions which cause/relieve suffering

- the story is an artificial construct to give Buddhism an illustrious past

Koller addresses the first point, writing:

Most likely the truth of the legend of the four signs is symbolic rather than literal. In the first place, they may symbolize existential crises in Siddhartha's life occasioned by experiences with sickness, old age, death, and renunciation. More important, these four signs symbolize his coming to a deep and profound understanding of the true reality of sickness, old age, death, and contentment and his conviction that peace and contentment are possible despite the fact that everyone experiences old age, sickness, and death. (49)

Scholars Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. address the second point noting that the story of the Four Signs was written over 100 years after Buddha's death and that early Buddhists were “motivated in part by the need to demonstrate that what the Buddha taught was not the innovation of an individual, but rather the rediscovery of a timeless truth” in order to give the belief system the same claim to ancient, divine origins held by Hinduism and Jainism (149).

The story may or may not be true, but it hardly matters because it has come to be accepted as truth. It appears first in full in the Lalitavistara Sutra (c. 3rd century CE) and, before that, may have undergone extensive revision via oral tradition. The symbolic meaning seems obvious and the claim it was written to enhance the standing of Buddhist thought, which had to contend with the established faiths of Hinduism and Jainism for adherents, also seems probable.

Ascetic Life & Enlightenment

Siddhartha at first sought out the famous teacher Arada Kalama with whom he studied until he had mastered all Kamala knew, but the “attainment of nothingness” he gained did nothing to free him from suffering. He then became a student of the master Udraka Ramaputra who taught him how to suppress his desires and attain a state “neither conscious nor unconscious”, but this did not satisfy him as it, also, did not address the problem of suffering. He subjected himself to the harshest ascetic disciplines, most likely following a Jain model, eventually eating only a grain of rice a day, but, still, he could not find what he was looking for.

In one version of his story, at this point he stumbles into a river, barely strong enough to keep his head above water, and receives direction from a voice on the wind. In the more popular version, he is found in the woods by a milkmaid named Sujata, who mistakes him for a tree spirit because he is so emaciated, and offers him some rice milk. The milk revives him, and he ends his asceticism and goes to nearby village of Bodh Gaya where he seats himself on a bed of grass beneath a Bodhi tree and vows to remain there until he understands the means of living without suffering.

Deep in a meditative state, Siddhartha contemplated his life and experiences. He thought about the nature of suffering and fully recognized its power came from attachment. Finally, in a moment of illumination, he understood that suffering was caused by the human insistence on permanent states of being in a world of impermanence. Everything one was, everything one thought one owned, everything one wanted to gain, was in a constant state of flux. One suffered because one was ignorant of the fact that life itself was change and one could cease suffering by recognizing that, since this was so, attachment to anything in the belief it would last was a serious error which only trapped one in an endless cycle of craving, striving, rebirth, and death. His illumination was complete, and Siddhartha Gautama was now the Buddha, the enlightened one.

Tenets & Teachings

Although he could now live his life in contentment and do as he pleased, he chose instead to teach others the path of liberation from ignorance and desire and assist them in ending their suffering. He preached his first sermon at the Deer Park at Sarnath at which he introduced his audience to his Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. The Four Noble Truths are:

- Life is suffering

- The cause of suffering is craving

- The end of suffering comes with an end to craving

- There is a path which leads one away from craving and suffering

The fourth truth directs one toward the Eightfold Path, which serves as a guide to live one's life without the kind of attachment that guarantees suffering:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

By recognizing the Four Noble Truths and following the precepts of the Eightfold Path, one is freed from the Wheel of Becoming which is a symbolic illustration of existence. In the hub of the wheel sit ignorance, craving, and aversion which drive it. Between the hub and the rim of the wheel are six states of existence: human, animal, ghosts, demons, deities, and hell-beings. Along the rim of the wheel are depicted the conditions which cause suffering such as body-mind, consciousness, feeling, thirst, grasping among many others which bind one to the wheel and cause one to suffer.

In recognizing the Four Noble Truths and following the Eightfold Path, one will still experience loss, feel pain, know disappointment but it will not be the same as the experience of duhkha, translated as “suffering” which is unending because it is fueled by the soul's ignorance of the nature of life and of itself. One can still enjoy all aspects of life in pursuing the Buddhist path, only with the recognition that these things cannot last, it is not in their nature to last, because nothing in life is permanent.

Buddhists compare this realization to the end of a dinner party. When the meal is done, one thanks one's host for the pleasant time and goes home; one does not fall to the floor crying and lamenting the evening's end. The nature of the dinner party is that it has a beginning and an ending, it is not a permanent state, and neither is anything else in life. Instead of mourning the loss of something that one could never hope to have held onto, one should appreciate what one has experienced for what it is – and let it go when it is over.

Conclusion

Buddha called his teaching the Dharma which means “cosmic law” in this case (not “duty” as in Hinduism) as it is based entirely on the concept of undeniable consequences for one's thoughts which form one's reality and dictate one's actions. As the Buddhist text Dhammapada puts it:

Our life is shaped by our mind; we become what we think. Suffering follows an evil thought as the wheels of a cart follow the oxen that draw it.

Our life is shaped by our mind; we become what we think. Joy follows a pure thought like a shadow that never leaves. (I.1-2)

The individual is ultimately responsible for his or her level of suffering because, at any point, one can choose not to engage in the kinds of attachments and thought processes which cause suffering. Buddha would continue to teach his message for the rest of his life before dying at Kushinagar where, according to Buddhists, he attained nirvana and was released from the cycle of rebirth and death after being served a meal by one Cunda, a student, who some scholars claim may have poisoned him, perhaps accidentally.

Before dying of dysentery, he requested his remains be placed in a stupa at a crossroads, but his disciples divided them between themselves and had them interred in eight (or ten) stupas corresponding to important sites in Buddha's life. When Ashoka the Great embraced Buddhism, he had the relics disinterred and then reinterred in 84,000 stupas across India.

He then sent missionaries to other countries to spread Buddha's message where it was received so well that Buddhism became more popular in countries like Sri Lanka, China, Thailand, and Korea than it was in India - a situation which, actually, is ongoing – and Buddhist thought developed further after that. Today, the efforts of Siddhartha Gautama are appreciated worldwide by those who have embraced his message and still follow his example of appreciating, without clinging, to the beauty of life.