Crucifixion as a punishment was practiced by several ancient cultures, but most notably adopted by the Roman Republic and later Roman Empire. Crucifixion was a method of hanging or suspending someone on the combination of vertical and horizontal poles until they died. In Christian theology and ritual, the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth is iconic for both his physical suffering as well as the way in which his crucifixion and subsequent resurrection from the dead transformed the lives of believers.

Origins

It remains difficult to trace the origin and evolution of this practice. The earliest examples are punishments for prisoners of war. It was then extended for specific crimes, most often the crime of treason, or plotting against the current monarch or throne.

Ancient Egypt utilized a process known as impaling. The body was literally impaled upon a pointed stake and death occurred quite rapidly as the major organs were pierced. The hieroglyph character for denoting this was a picture of it, with the phrase, "to give on the wood." The practice is mentioned during the reigns of Sobekhotep II, Akenaten, Seti, and Ramesses IX. Merneptah (1213-1203 BCE) "caused people to be set upon a stake" south of Memphis.

In the region of ancient Mesopotamia (the later empires of Assyria, Babylon, and Persia), we have a similar process. When the Assyrian king Sennacherib conquered the Israelite city of Lachish in 701 BCE, his wall depictions show prisoners being strung up on poles, with the pole inserted up through the ribs. The purpose of this excruciating punishment was to emphasize the cruelty and terror of what awaited prisoners and rebels.

During the Persian period, the Book of Esther related how Esther saved her people from the planned pogrom against the Jews by Haman, with the irony of the death he had planned for them:

King Xerxes replied to Queen Esther and to Mordecai the Jew, “Because Haman attacked the Jews, I have given his estate to Esther, and they have impaled him on the pole he set up. (Esther 8:7)

The use of impalement by the Phoenicians (Canaan and Lebanon) was translated to the commercial colonies they established around the Mediterranean.

The Hellenistic/Roman Period

The conquests of Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) brought a paradigmatic shift to the region of the Eastern Mediterranean. Greek culture, government, language, religion, and philosophy were utilized throughout, including adaptations by the Jews. The Greeks often opposed impalement in some of their literature, but Herodotus related that a Persian general was executed in 479 BCE that would later become standard: "They nailed him to a plank and hung him up" (Histories, IX.120–122). It was reported that Alexander himself impaled 2000 prisoners at his siege of the Phoenician city of Tyre.

It is in these later writings that we come upon the problem of language and translation. Ancient Greek utilized two words: anastauroo ("a wooden pole") and apotumpanizo ("impale on a plank"). In adaptations to Latin, crux ("a tree or a construction of wood to hang executed criminals") became combined to give us the English "crucifixion," now denoting specifically a cross. The problem is that the surviving manuscripts of both the Jewish Scriptures and the New Testament all use "crucifixion" without distinguishing whether it was impalement, or a later form that evolved. For example, Deuteronomy 21:22-23 instructs:

If someone guilty of a capital offense is put to death and their body is exposed on a pole, you must not leave the body hanging on the pole overnight. Be sure to bury it that same day, because anyone who is hung on a pole is under God's curse. You must not desecrate the land the Lord God is giving you as an inheritance.

The Greek Scriptures (the Septuagint) used "crucifixion" here for "hung on a pole." Both Paul (in Galatians) and the gospel writers utilized this passage as a prophetic prediction of events in the death of Jesus.

There is a story in Flavius Josephus' Antiquities concerning one of the Hasmonean kings, Alexander Jannaeus (King of Judea from 103-76 BCE). With his support of the Sadducees over the proper rituals in the Temple, he fell out with the emerging sect of the Pharisees. This was also a period of civil disruptions; the Pharisees supported Jannaeus' enemies. During the Jewish holiday of Sukkot:

Upon the advice of a Sadducee favorite named Diogenes he caused in one day 800 captured Pharisees to be nailed on crosses [crucified]. This monstrous deed is rendered still more horrible by the legendary statement that he caused the wives and children of the condemned to be executed before their eyes, while he, surrounded by feasting courtiers and courtesans, enjoyed the bloody spectacle. (XIII, 356-83)

Roman Crucifixion

Rome absorbed and adopted many concepts and practices from the provinces. We know about Roman crucifixions through the writings of Cicero, Plautus, Seneca, Tacitus and Plutarch. One of the more infamous occasions was when Marcus Crassus punished the survivors of the slave rebellion under Spartacus (73-71 BCE, the Third Servile War). Crassus ordered approximately 6000 slaves to be crucified on either side of the Appian Way (from Naples to Rome). Their bodies were left there in a decayed state to emphasize what happens to rebels.

The Roman penal system recognized different classes and the status of each. Citizens and the upper classes were executed by decapitation for major crimes (which included treason). The lower classes, depending upon the crime, were charged with fines, but if convicted of murder or treason, the Roman government executed them in the arenas, as part of the venatio games (wild beast hunts). Having wild animals (lions, panthers, bears) already there, they became the executioners. Crimes by slaves were punished by crucifixion. There was a tacit assumption that a slave was more treasonous than others. Roman law stated that if a slave killed a master or mistress, the entire household of slaves had to be crucified on the premise that none of them revealed the plot, so it must have been a conspiracy. Often considered a waste of resources and property by some, this type of execution was rare.

We also have the famous story of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) when he was kidnapped by pirates in the ancient Mediterranean. While awaiting his ransom payment, he told them that he would come back and crucify all of them, which he did. Pirate kidnappers targeted Roman magistrates for ransom; this was considered treason, and so the punishment was crucifixion.

The Process

Based on Roman literature as well as descriptions in the provinces, crucifixion was an established routine. There were special military teams led by a centurion, and in the provinces, the soldiers were selected from the local auxiliaries (natives who had joined the Roman army). The victim was stripped and then lashed (scourged). As part of the public humiliation, he/she was led through the streets and remained naked. Christian art portrays Jesus with a decent loincloth on the cross, but the nakedness was maintained as part of the humiliation. There was a public plaque (titulus) indicating the crime. The shedding of blood and the concept of corpse contamination meant that the executions took place outside the city walls. The most popular spot was along one of the main roads leading into the city. This also served as propaganda purposes to demonstrate Roman law and order.

These killing fields contained permanent, upright poles. The victim did not carry the whole cross, but only the cross-beam. The combined pole and cross-beam weighed approximately 135-180 kg (300-400 pounds). After scourging (the trauma and the loss of blood), there was a risk that the victim could die before arriving at the site of execution. The necessity of keeping the victim alive led to the practice of the legions commandeering someone from the crowd to help carry the beam when the victim succumbed. This is the role of Simon of Cyrene in the gospel versions.

Upon arrival, the victim was either tied or nailed to the cross-beam which was then hoisted up and connected to the vertical pole (with ladders and pulleys). We have evidence of the use of nails from several sources. These were 13-18 cm (5-7 in) long tapered iron spikes. The application of the nails varied. Seneca reported that some were hung upside down, or with arms stretched out on either side. Josephus reported seeing crucifixion victims at the siege of Jerusalem (70 CE) where the soldiers positioned them in various poses to amuse themselves out of anger and hatred. Some people collected the nails as magical amulets.

Despite the iconography of later Renaissance art, the nails were not placed in the palms. In the Gospel of John, when doubting Thomas did not believe that Jesus was resurrected and wanted to see his "hands," the Greek for "hand" meant anything from the tip of the fingers to the elbow, but the literal understanding became incorporated in art. Several years ago, historians and scientists began experimenting on cadavers to fully understand how a crucifixion victim died. It quickly became apparent that nailing through the palm would result in the weight of the body immediately tearing through. Rather, the nail was inserted at the wrist, at the juncture of the ulna and radius. These experiments on cadavers have resulted in the understanding that the cause of death for a victim was a combination of bodily trauma, loss of blood, and ultimately asphyxiation, as it became harder and harder to lift the weight of the body up to breathe.

Seneca also reported that some were impaled in their private parts. This may be a reference to what was known as a horn, or a pointed fixture halfway down, as a 'seat' for the victim. This may have been a way in which to help support the body, although if pointed, excruciatingly painful.

There were variations for nailing the feet; sometimes crossed over, but more often the nails were inserted into the side of the pole. We know this from one of the rare skeletons of a crucifixion victim in Jerusalem in the 1st century CE. In the tomb of a wealthy family, one of the ossuaries (bone boxes for collecting bones) included the skeleton of Jehohanan, who may have died by crucifixion. Apparently, when it was time to take him down, the nail through the side of the foot had bent; someone simply cut his feet off. We now have a fossilized lump that includes the nail, the heel fragment, and a bit of olive wood.

The gospel versions of the crucifixion of Jesus include many of the standard elements. It demonstrates that the writers were familiar with the process, although we cannot verify that they witnessed this crucifixion (Mark, the first gospel was written 40 years after the death of Jesus). Support for the victim also included "the vinegar mixed with gall" as reported in the gospels. One of the purposes of crucifixion was to keep the victim alive as long as possible so that everyone could appreciate the result of rebelling against Rome. This was the equivalent of using a type of smelling salt as a means of revival when the victim began to flag. Crucifixion victims were expected to survive for several days. It is problematic in the gospels that Jesus died within three hours.

Depending upon circumstances, limited personnel, or other reasons, victims were put to death early. This was done by fracturing the legs or eliminating support for the body. It is only in John's gospel that rather than having his legs broken, a soldier pierced Jesus' side to verify death.

Eternal Damnation

The crucifixion of Jesus indicates that, in Roman eyes, he was a traitor. Jesus had preached a kingdom that was not Rome. Rome had done this with many 'messianic firebrands' leading up to the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE. When Rome convicted a rebel, the punishment included a ban on any funeral rituals. This meant that the victim would be forever caught between the living and dead in Hades. The victims, like those of Crassus, hung on the crosses until the vultures finished them; the bones were simply thrown into a nearby ditch for the feral dogs. Crucifixion and arena victims in Rome were simply dragged and thrown into the Tiber.

This is the reason why archaeologists have found so few examples of crucified bodies in burial layers. But since the discovery of Jehohanan, in 2007, in the Po valley, a skeleton was discovered with a hole in the heel bone, possibly caused by a nail. Another case has recently been uncovered in Fenstanton in the United Kingdom (2017). Studies of the relic known as the Shroud of Turin, with the image of a crucified man, are often used to substantiate details of crucifixion. On the Shroud, the man is bleeding from the wrists, with a gash on the side.

However, we are aware of the many magistrates of Rome who were open to bribery. This is the function of Joseph of Arimathea, the "rich man" who already had a tomb prepared in the gospels. He asked Pilate for the body for proper burial.

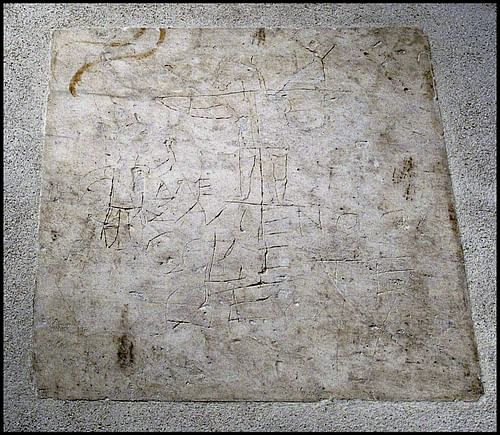

Alexamenos Graffito & Staurogram

Our earliest depiction of a Christian crucifixion is found in a wall mural (which is now on display in the Palatine Museum in Rome. This graffito is perhaps one of the earliest depictions of Christ with the head of an ass on a cross. It apparently mocked the idea of a crucified god.

The reference to donkey-worship comes from a story recounted by the Roman historian Tacitus, in which a group of Jews, expelled from Egypt, wandered through the desert, exhausted and dying of thirst, until they were led to water by a herd of wild asses. In turn, they started worshipping the animal that delivered them. Tertullian addressed the slander: "You [non-Christians] say that our god is the head of an ass, but you in fact worship the ass in its entirety, not just the head. You throw in the patron god of donkeys and all the beasts of burden, cattle, and wild animals. You even worship their stables [a reference to the obsession of chariot races and horses]. Perhaps this is your charge against us that in the midst of all these indiscriminate animal lovers, we save our devotion for asses alone." (Apology, XI)

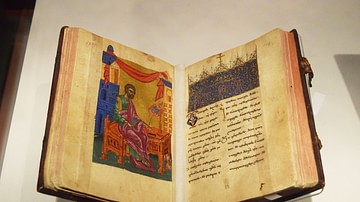

Another early depiction of the cross was the staurogram (stauros is Greek for "cross"). This was the combined first two letters of the name of Christ, the chi and rho, superimposed. This symbol was used by early Christian scribes as a shorthand note in their manuscripts. It is also the sign that Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) claimed to have seen in the sky before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312 CE), which led to Constantine’s conversion to Christianity.

Devotional Crucifixions

The Catholic Church officially discourages voluntary and self-crucifixions as a devotional practice. However, they remain popular in the Philippines and Mexico, usually carried out during Easter week. The victims do not die, but it is considered an honor to experience the pain and suffering of Christ.