Publius Ovidius Naso, more commonly known to history as Ovid (43 BCE - 17 CE), was one of the most prolific writers of the early Roman Empire. His works of poetry, mostly written in the form of elegiac couplets, influenced many of the great authors throughout history including Chaucer, Milton, Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe. Beloved by the people of Rome, he made the tragic mistake of angering Emperor Augustus and spent the remainder of his life in exile.

Early Life

The descendant of an old established equestrian family, Ovid was born on March 20, 43 BCE at Sulmo in Abruzzo, 145 km (90 miles) east of Rome. By the time of his birth the Republic had fallen and the heir apparent to the fallen Julius Caesar, Octavian (the future Augustus), was in pursuit of his assassins; a civil war had begun. Like many others of his generation, Ovid's family, especially his father, wanted him to pursue a career in law and politics, but Ovid's life-long dream was something completely different. He was sent to Rome to complete his education under the tutelage of the orator Arellius Fuscus and the rhetorician Porcius Latro. A distinguished student, especially in rhetoric, he later toured the Greek islands as many young Roman students did to further one's education.

Despite the urging of his parents - his father often reprimanded him for writing poetry - this lover of language abandoned public life after only a handful of minor judicial posts for the life of a poet. With the urging of the orator and patron of arts Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, he soon gained success as a writer and was soon the most well-known poet in Rome. Unfortunately, this notoriety could not protect him, and in 8 CE he was banished from Rome.

Famous Works

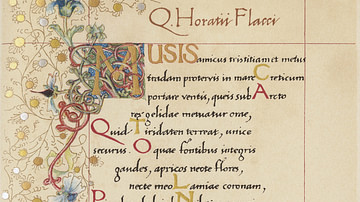

A contemporary of the Roman historian Livy, Ovid, along with the poets Virgil and Horace is thought by many historians to have created a poetic style comparable to the Greek writers of the ancient past. However, unlike Virgil and Horace, Ovid was not considered part of Emperor Augustus' inner circle at the imperial court. For reasons that are unclear to modern historians, Ovid did not endear himself to the emperor. This may have been due to the type of poetry Ovid wrote: advice to the young lover. One historian even said that to Ovid love was the only game worth playing.

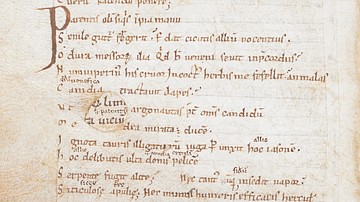

His first book of poetry was the extremely successful Amores or 'The Book of Love,' published in 22 BCE. It told in a very lighthearted style about the misadventures of a young man and his love for an unobtainable young girl. His other works focused on a variety of topics: Heroides or 'Heroines' was a series of 15 letters supposedly written by Greek and Roman mythological female figures such as Penelope and Dido to their lovers who had either mistreated or abandoned them. His Mediacamina Faciei Femineae not only defended a Roman woman's use of cosmetics but also provided recipes. Another work Remedia Amoris or 'Remedies for Love' provided guidance to lovers on how to end a relationship. Ars Amatoria or 'The Art of Love' was three books written in 2 CE that spoke of the acts of courtship and erotic intrigue, giving advice to both men and women. A good example of this advice can be found in Book I where he wrote,

The first thing you must do is to find an object for your love, you who now for the first time come to fight in this new warfare. The next task is to win the girl that attracts you; the third task is to make your love endure. (Branyon, 57)

Ars Amatoria has long been considered one of the possible reasons for his exile.

Metamorphoses

His most famous work, at least to most modern readers, is Metamorphoses, 15 books composed in dactylic hexameter, a collection of tales garnered from classical and Near Eastern myths and legends, a chronology from the creation of the world to the death of Caesar. It was an epic poem that spoke not only of humanity's interaction with the gods but also of heroes and heroines such as Perseus, Theseus, Hector, and Achilles. It is one of Ovid's few works not written in couplets.

Completed prior to his exile, he opened Book I with a statement of his purpose,

My mind is bent to tell of bodies changed into new forms. O gods, for you yourselves have wrought changes, breathe on these my undertakings, and bring down my song in unbroken strains from the world's very beginning even unto the present time. (Metamorphoses, 3)

He ended Book XV by speaking of both Rome's and his own future,

Wherever Rome's power extends over the conquered world, I shall have mention on men's lips, if the prophecies of bards have any truth, through all the ages shall I live in fame. (Metamorphoses, 311)

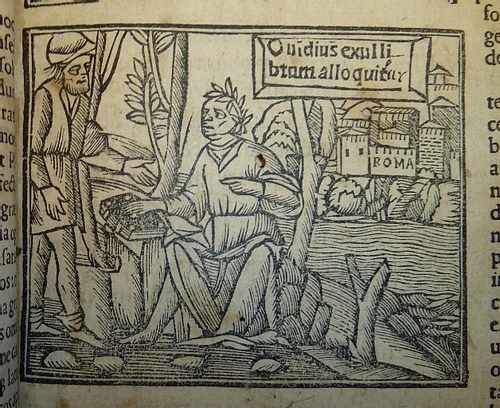

Exile

To say the least, the subject of Ovid's erotic poetry was in sharp contrast to the moral reform proposed by Emperor Augustus who, in principal, believed that part of the Republic's demise and the current dire status of the Empire resided in a lack of morals, a problem about which Cicero had written decades previously, before Augustus had had him assassinated in 43 BCE. The emperor wanted his empire to return to a stricter observation of many of Rome's older traditions, especially in the area of religion and the marriage bed. Unfortunately, Ovid did not believe these reforms affected everyone equally, more specifically the imperial household, for the emperor was well-known for his many mistresses, and his daughter Julia was a renowned adulterer; she would eventually be banished, returning to Italy only to die of malnutrition in 15 CE.

Sadly, Ovid could not keep his opinions to himself, expressing them within the lines of his poetry. He wrote that the emperor's private life and marriage were in sharp contrast to the stiff rules he established for the general population. The outspoken poet was also candid about the emperor's wife, Livia. In his poetry he believed a woman had the right to use cosmetics; however, with Livia, he said she was too busy to pay much attention to her appearance, despite having a staff to watch over her wardrobe and even a masseuse.

Emperor Augustus was not pleased with the content of Ovid's poetry, and while the real reason became a state secret, Ovid was banished in 8 CE to Tomis, Constanta in modern-day Romania, in Ovid's words a place with a most "wretched climate." Some historians point to a possibility that Ovid was involved in the supposed Julia scandal. Whatever may have been the reason for his exile, Augustus publicly claimed the poet encouraged female adultery. In his own defense, Ovid maintained that he made an error, not a crime. Further, all of his works were banned from Roman public libraries. Luckily for future generations, however, because of his popularity among many private collectors, his works were able to survive.

There are some who believe his exile was due to the atmosphere of the times. People in the city were restless and near rebellion in the provinces. Others contend he may have heard or seen something, and the emperor needed to silence him, exile being the most logical choice. Despite both public and private pleading, the emperor and even his heir Tiberius would not relent, and the poet spent the remainder of his life away from Rome at Tomis. While in exile, he continued to write; among these works were four books of poems entitled Epistulae ex Ponto or 'Epistles from Pontus.' and Tristia or 'Sorrows,' poems to his wife. In 17 CE Ovid died while still in exile. Although he requested to be buried in Rome, no one is sure if his request was honored.