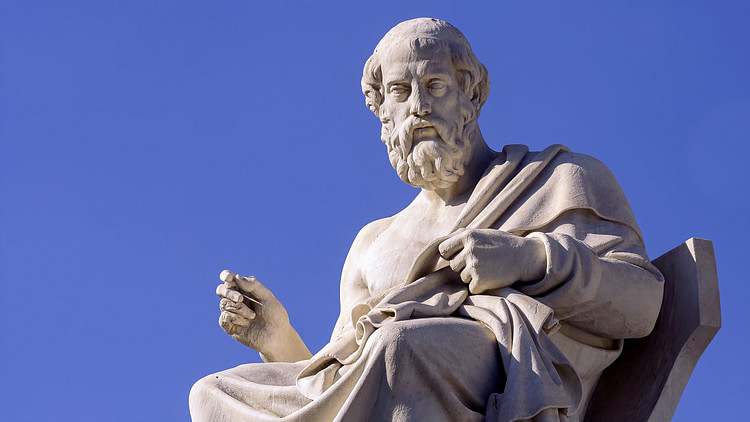

Plato (l. 424/423 to 348/347 BCE) is the pre-eminent Greek philosopher, known for his Dialogues and for founding his Academy in Athens, traditionally considered the first university in the Western world. Plato was a student of Socrates and featured his former teacher in almost all of his dialogues which form the basis of Western philosophy.

The son of Ariston of the deme Colytus, Plato had two older brothers (Adeimantus and Glaucon), who both feature famously in Plato's dialogue Republic, and a sister Potone. According to the later writer Diogenes Laertius (l. c. 180 to c. 240, and considered often unreliable), his birth name was Aristocles, and "Plato" was a nickname given him by his wrestling coach because of his broad shoulders (in Greek, Platon means broad).

This claim has been challenged by scholar Robin Waterfield who also places Plato's birth date at 424/423 BCE, rejecting the traditional birth date of 428/427 BCE. Waterfield writes:

There are several factors that point to a birth date later than 428/7. The most important is that there is no evidence that he fought in any of the last battles of the Peloponnesian War in 406 and 405, so he was probably still under the age of twenty. Athens was critically short of manpower at the time, so he would certainly have been called up. (Plato of Athens, 3)

Waterfield also notes Plato's Letter 7, regarded as authentic, in which he mentions his plans to take part in the public life of Athens once he comes of age, placing him under the age of 20 in 405 BCE (3). The traditional birth date of 428/427 BCE assigned to Plato, therefore, must be regarded as inaccurate.

Plato's family was aristocratic and well-connected politically and it seems he was expected to pursue a career in politics. His interests, however, though they included politics, also tended toward the arts, and in his youth, he wrote plays and, perhaps, poetry.

After abandoning his political and literary pursuits and devoting himself to Socrates, even throughout his trial and execution, Plato wrote the foundational philosophic works of the ancient world, which would go on to influence world culture. The three great monotheistic religions of the world owe much to Platonic thought whether directly or through the works of his student and friend Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE), whose teachings remained consistent with Plato's vision of the importance of caring for one's soul and maintaining a virtuous lifestyle even though Aristotle would depart from some of the specifics of Plato's philosophy.

Socrates & Plato

When he was in his late teens or early twenties, Plato heard Socrates teaching in the market and abandoned his plans to pursue a political or literary career; he burned his early work and devoted himself to philosophy.

It is likely that Plato had known Socrates, at least by reputation, since youth. The Athenian politician, Critias (l. c. 460-403 BCE), was Plato's mother's cousin and studied with Socrates as a young man. It has been suggested, therefore, that Socrates was a regular visitor to Plato's family home. However this may be, nothing is suggested by the ancient writers to indicate Socrates' influence over Plato until the latter was about 20 years old.

Diogenes Laertius writes that Plato was about to compete for the prize in tragedies in the theatre of Bacchus when "he heard the discourse of Socrates and burnt his poems saying, 'Vulcan, come here; for Plato wants your aid' and from henceforth, as they say, being now twenty years old, he became a pupil of Socrates." Nothing is clearly known of Plato's activities for the next eight years save that he studied under the elder philosopher until the latter's trial and execution on the charge of impiety in 399 BCE.

Socrates' execution impacted Plato significantly, and he left Athens to travel, visiting Egypt and Italy among other places, before returning to his homeland to write his dialogues and set up the Academy. His Dialogues almost all feature Socrates as the main character, but whether this is an accurate portrayal of Socrates' actions and beliefs has long been contested.

Plato's contemporary, Phaedo, also one of Socrates' students (and best known for Plato's dialogue named after him) is said by Laertius to have contended that Plato placed his own ideas in Socrates' mouth and made up the dramatic situations of his dialogues. Other philosophers and writers of the time have also questioned the accuracy of Plato's depiction of Socrates but seem in agreement that Plato was a very serious man with lofty ideas which were difficult for many to grasp.

Critics of Plato

Though he was respected as a philosopher of enormous talent in his lifetime (he was at least twice kidnapped and ransomed for a high price), he was by no means universally acclaimed. The value of Plato's philosophy was said to have been questioned most strenuously by the Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope who considered Plato an 'elitist snob' and a 'phony'.

Again, according to Laertius, when Plato defined a human being as a bi-ped without feathers, Diogenes is said to have plucked a chicken and presented it in Plato's classroom, crying, "Behold, Plato's human being." Plato allegedly replied that his definition would now need to be revised, but this concession to a critic seems to have been an exception rather than the rule. Criticisms aside, however, Plato's work exerted an enormous impact on his contemporaries and those who followed.

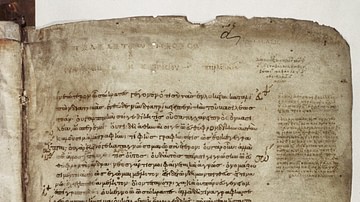

Plato's Dialogues

Plato's Dialogues of the Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo are commonly collected under the title The Last Days of Socrates, and this four-act drama shows Socrates before, during, and after his trial in the Athenian court. Scholar I. F. Stone praises Plato's Apology as "a masterpiece of world literature, a model of courtroom pleading; and the greatest single piece of Greek prose that has come down to us. It rises to a climax which never fails to touch one deeply" (210), and Stone is certainly not alone in his estimation of the work.

The Apology is considered universally as the beginning of western philosophy. Plato's Euthyphro, however often overlooked, sets the stage for Apology while also providing the reader with another glimpse into the values Socrates may have held and the way in which he went about teaching these values. Perhaps it was Plato's intention to show why Socrates would have been put on trial in the first place, since the young fundamentalist, Euthyphro, is hardly hurting anyone with his beliefs and, no doubt, the case he brings against his own father would have been thrown out of court. As Euthyphro clearly and ardently believes in the gods of Greece, and as Socrates soundly shows him that his beliefs are inconsistent and incomplete, the dialogue illustrates what could have been meant by the charge leveled against Socrates of "corrupting the youth".

In the Apology, Plato recounts the foundational speech of Socrates (whether factual or his own creation) in defending the importance of the philosopher's - or anyone's - right to stand up for their personal convictions against the opinion of society. In defending himself against the unjust charges of his accusers, Socrates says:

Men of Athens, I honor and love you; but I shall obey God rather than you and, while I have life and strength, I shall never cease from the practice and teaching of philosophy, exhorting anyone whom I meet after my manner, and convincing him saying: O my friend, why do you who are a citizen of the great and mighty and wise city of Athens care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honor and reputation and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all? Are you not Ashamed of this? And if the person with whom I am arguing says: Yes, but I do care; I do not depart or let him go at once; I interrogate and examine and cross-examine him, and if I think that he has no virtue, but only says that he has, I reproach him with undervaluing the greater, and overvaluing the less. And this I should say to everyone whom I meet, young and old, citizen and alien, but especially to the citizens, inasmuch as they are my brethren. For this is the command of God, as I would have you know: and I believe that to this day no greater good has ever happened in the state than my service to the God. For I do nothing but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, not to take thought for your persons and your properties, but first and chiefly to care about the greatest improvement of the soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money, but that from virtue come money and every other good of man, public as well as private. This is my teaching, and if this is the doctrine which corrupts the youth, my influence is ruinous indeed. But if anyone says that this is not my teaching, he is speaking an untruth. Wherefore, O men of Athens, I say to you, do as Anytus bids or not as Anytus bids, and either acquit me or not; but whatever you do, know that I shall never alter my ways, not even if I have to die many times.

(29d-30c)

This speech has continued to inspire activists, revolutionaries, and many others for the past two thousand years but would be meaningless if Socrates had not chosen to place his life on the line to stand behind his words. The dialogue of the Crito shows Socrates doing just that as it is a discussion of the law and how, as a citizen of the state, one should obey the law even if one disagrees with it.

Socrates' friend Crito suggests he escape, and offers him the means to do so, but Socrates rejects the offer, pointing out that his life's work would mean nothing were he to attempt dodging the consequences of his words and actions. This dialogue, set in Socrates' prison cell as he awaits execution, prepares a reader for the final act of the drama, Plato's Phaedo, in which Socrates attempts to prove the immortality of the soul.

Plato very purposefully states in the dialogue that he himself was not present that day and leaves it to his main character, the narrator Phaedo, to relate the events of Socrates' last hours which were devoted entirely to philosophical discourse with his students. Plato has the character of Socrates say, at one point:

I will go back to what we have so often spoken of, and begin with the assumption that there exists an absolute beauty, and an absolute good, and an absolute greatness, and so on. If you grant me this, and agree that they exist, I hope to be able to show you what my cause is, and to discover that the soul is immortal

(100b)

If the reader does grant this to Socrates then, indeed, the soul is proven immortal; if one does not grant the assumption, however, it is not. The assumption that there exists "an absolute good and an absolute greatness" is quite a large one, and Plato's dialogues, no matter the subject they treat, may be read as a life's work to prove the truth of what Socrates asks an audience to grant him.

The Quest for Truth

The Dialogues of Plato universally concern themselves with the quest for Truth and the understanding of what is Good. Plato contended that there was one universal truth, which a human being needed to recognize and strive to live in accordance with. This truth, he claimed, was embodied in the realm of Forms. Plato's Theory of Forms states, simply put, that there exists a higher realm of truth and that our perceived world of the senses is merely a reflection of the greater one.

When one looks at a horse, then, and values that horse as 'beautiful', one is responding to how closely that particular horse on earth corresponds to the 'Form of Beauty' in the realm of Forms. In order to recognize the 'Form of Beauty', one needs first be able to recognize that this perceived world is merely an illusion or a reflection and that what one calls 'beautiful' on earth is not beautiful in itself but is only 'beautiful' in as much as it participates in the 'Form of Beauty' (a concept further explored in Plato's famous 'Allegory of the Cave' in Book VII of Republic). This central concept of Platonic thought is a refutation of the sophist Protagoras' claim that "Of all things, a man is the measure", meaning that reality is subject to individual interpretation. Plato completely rejected this claim and spent his life trying to refute it through his work.

The old saying, "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder" would be completely unacceptable to Plato. If Person A claims a horse is beautiful and Person B claims that the horse is not, one of them needs to be right and one wrong in their claim; they cannot both be correct. According to Plato, the one who is right will be the one who understands and recognizes the Form of Beauty as it is expressed in that particular horse. This claim, of course, stands in direct opposition to Protagoras' assertion that "Man is the measure of all things", and, it seems, it was supposed to. Plato devoted most of his life to trying to prove the reality of the realm of Forms and to disprove Protagoras' relativism, even to the last dialogue he wrote, the Laws.

In all of Plato's work, the one constant is that there is a Truth which it is the duty of a human being to recognize and strive for, and that one cannot just believe whatever one wants to (again, a direct challenge to Protagoras). Even though he never conclusively proved the existence of the Forms, his standard inspired later philosophers and writers, notably Plotinus, who is credited with founding the Neo-Platonic school, which exerted significant influence on early Christianity.

Plato's Influence

The enormity of Plato's influence was recorded by Diogenes Laertius who, though often considered unreliable, as noted above, seems to provide an accurate assessment in this case:

He was the first author who wrote treatises in the form of dialogues, as Favorinus tells us in the eighth book of his Universal History. And he was also the first person who introduced the analytical method of investigation, which he taught to Leodamus of Thasos. He was also the first person in philosophy who spoke of antipodes, and elements, and dialectics, and actions (poiêmata) and oblong numbers, and plane surfaces, and the providence of God. He was likewise the first of the philosophers who contradicted the assertion of Lysias, the son of Cephalus, setting it out word for word in his Phaedrus. And he was also the first person who examined the subject of grammatical knowledge scientifically. And as he argued against almost every one who had lived before his time, it is often asked why he has never mentioned Democritus.

(Lives, XIX)

In this passage, Laertius is essentially claiming that Plato contradicted or significantly improved upon all of the accepted theories which came before him, and an important recognition of his influence on the world to the present day is summed up by the 20th-century philosopher Alfred North Whitehead who stated, "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato" (Baird, 67).

This influence is perhaps best represented by Plato's most famous dialogue, Republic. Professor Forrest E. Baird writes, "There are few books in Western civilization that have had the impact of Plato's Republic - aside from the Bible, perhaps none" (Ancient Philosophy, 68). Republic has been denounced as a treatise on fascism (by Karl Popper, among others) and praised as an eloquent and elevating work by scholars such as Bloom and Cornford. The dialogue begins with a consideration of what Justice means and goes on to develop the ideal, perfect State. Throughout the piece, Plato's ideas of Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and Justice are developed as they are explored by Socrates and his interlocutors.

While the work has traditionally been understood as Plato's attempt to outline his model for the perfectly just and efficient society, an important point is often overlooked: the character of Socrates very clearly states in Book II. 369 that they are creating this 'city' as a means to better understand the function of the perfect 'soul'. The society which the men discuss, then, is not intended to reflect an actual physical political-social entity but rather to serve symbolically as a means by which a reader may recognize strengths and weaknesses in his or her own constitution.

The young poet and playwright Plato had been is always present in crafting the mature works of the philosopher Plato, and, in all the dialogues, a reader is expected to consider the work as carefully as one would a poem. Unlike his famous student Aristotle, Plato never clearly spells out the meaning of a dialogue for a reader. The reader is supposed to confront the truths which the dialogue presents individually. It is this combination of artistic talent with philosophical abstractions which has assured Plato's enduring value as a philosopher and artist.

Aristotle & Plato's Legacy

While Aristotle disagreed with Plato's Theory of Forms and many other aspects of his philosophy, he was profoundly affected by his teacher; most notably in his insistence on a right way of living and a proper way to pursue one's path in life (as outlined most clearly in Aristotle's Nichomachean Ethics). Aristotle would go on to tutor Alexander the Great and, in so doing, would help spread the brand of philosophy Plato had established to the known world.

Plato died at the age of 80 in 348/7 BCE, and leadership of the Academy passed to his nephew Speusippus. Tradition holds that the Academy endured for nearly 1,000 years as a beacon of higher learning until it was closed by the Christian Emperor Justinian in 529 in an effort to suppress pagan thought. Ancient sources, however, claim that the Academy was severely damaged in the First Mithridatic War in 88 BCE and almost completely destroyed in the Roman dictator Sulla's sack of Athens in 86 BCE. Even so, some version of the Academy seems to have survived until it was closed by the adherents of the new religion of Christianity.

Plato's Academy was a wooded garden located near to one of his homes and not a university as one would picture such an institution today, and so the area underwent many changes both before and after Plato's school was established there and seems to have been a center of learning for centuries.

The Roman writer Cicero claims that Plato was not even the first to have a school in the gardens of Academia, but that Democritus (c. 460 BCE) was the original founder and leader of a philosophical school in the locale. It is also established that Simplicius was the head of a school in the gardens, which was still known as the Academy, as late as 560. Even so, in the present day, the site is known, and honored, as that of Plato's Academy, reflecting the importance of the philosopher's influence and respect for his legacy.