A praetor was a senior magistrate in ancient Roman government, who was granted executive or imperium powers similar to that of the consuls. Although originally assigned legal authority over the courts, his executive powers allowed him to command the army and, if needed, even preside over the Roman Senate. Candidates usually had to serve as a praetor before they could stand election to the consulship.

The Cursus Honorum

After the ousting of the last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, in 509 BCE, the Roman Republic was established, placing executive power in the hands of two consuls, elected annually by the Assembly. They were the political and military heads of state, presiding over the Senate, conducting foreign affairs, proposing laws, and commanding the army. The yearly election of two consuls prevented any one man from gaining too much power. As a safeguard, each consul had the right to veto the other's decision (intercessio). Each consul was also required to answer for any decision made during his time in office.

However, the duties of running a government the size of Rome proved overwhelming, and lesser magistrates were necessary to help administer the needs of the state. As a result, the cursus honorum ("path of honor") evolved. These offices became a road to the consulship, where an interval of two years was required between each office. The lex Villia Annalis of 180 BCE set a minimum age for each magistrate (39 for praetors and 42 for consuls). The law would be later confirmed by the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla around 82 BCE.

After serving in the Roman army for at least ten years, an individual with political ambitions could pursue the first elected rung on the ladder at the age of 28: the quaestor. Although only serving for one year, the quaestor's primary duties included overseeing the state finances: its treasuries, accounting procedures and record keeping. Other duties included administrating public properties and collecting taxes. While assigned to one of the provinces and serving as an assistant to a senior magistrate, he might also serve as a tax collector and recruiting officer.

Next came the aedile – four were elected each year – who supervised the city's public works: the roads, the water supply, the upkeep of the temples, and the running of the public games. Like all rungs on the ladder, the aedile was unpaid. This meant that only those with the necessary financial support could hold the office.

The next step on the path was the praetor. Although his primary function was to conduct judicial proceedings, both civil and provincial, he was also endowed with executive or imperium power, similar to that of the consul, and he could perform most of their duties when required. The various functions of the magistrates expanded as Rome expanded into the Balkans, Asia, Africa, and Spain. However, despite the increase in their responsibilities, the yearly elections of all magistrates still checked an individual's power.

Origins

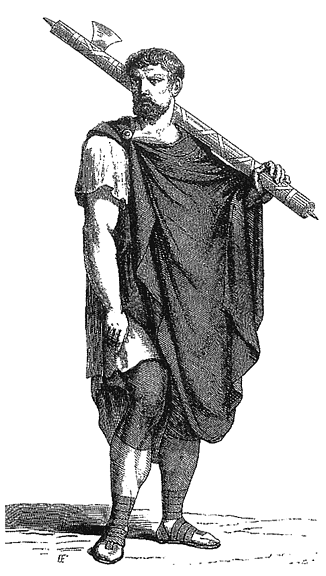

Initially, at the founding of the Republic, the term praetor (it means "to go before" – from prae ire) was used to designate the two annually elected republican magistrates who served as the heads of state. In 367 BCE, at a time when only patricians could hold any government office, a new law, the Licinio-Sextian rogations, added a third praetor. The law, or compromise, was the creation of the tribunes Gaius Licinius Stolo and Lucius Sextius Lateranus and allowed, among other provisos, the intermarriage between patricians and plebeians. The establishment of a third praetor was a concession to the law's patrician opposition. As a result, the original two praetors were renamed as consuls. However, the third praetor still retained his imperium powers and the ability to perform all of the functions of a consul, both in Rome and in the provinces. His official duty was overseeing the courts, a position that allowed him even to impose the death penalty when appropriate. When the consuls were absent from Rome (which happened quite often), the praetor became the chief magistrate. As a symbol of his office, he wore a purple cloak and was escorted by lictors, who carried with them the fasces, a bundle of rods wrapped around an axe. It designated his right, when necessary, to use force.

Since the early days of the Roman Republic, the plebeians had fought for the right to participate in their government. After a lengthy struggle, often referred to as the Conflict of the Orders, the plebeians gained a voice in the plebeian Assembly, and in the 4th century BCE, they were finally allowed to become an integral part of the Roman government, with the right to become a consul. The first plebeian consul was elected in 366 BCE, and from 342 BCE onward, one of the two consuls had to be a plebeian. Eventually, plebeians gained access to all political offices: quaestor, aedile, and praetor: the first plebeian praetor was elected in 337 BCE.

Evolution of the Role

The First Punic War (264-241 BCE) against Carthage brought a number of changes to Rome. Around 244 BCE, the number of praetors was increased from one to two: one being designated as praetor urbanus (internal affairs) while the second became praetor inter peregrinos (foreign affairs). Around 228 BCE, the number was increased to four to provide commanders for Sicily and Sardinia, lands acquired from the war with Carthage. Exercising their imperium powers, praetors were continually used as commanders as the borders were expanded through Roman warfare. This remained true even during the early Roman Empire. Stephen Dando-Collins in his Legions of Rome wrote how Vespasian (the future Roman emperor, r. 69-79 CE) and his brother Sabinus served as praetors, commanding legions during the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 CE.

The defeat of Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) gave control of Spain to Rome, adding the provinces of Nearer Spain and Further Spain to Rome's realm. Two more praetors would be added – bringing the total to six – to serve in these newly acquired Spanish provinces. The war in Spain would continue for decades until Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) completed the conquest. Territory acquired through wars with Philip V of Macedonia, his son Perseus, and Antiochus, king of the Seleucid Empire, expanded the Republic further east. With extensive expansion, two consuls proved to be inadequate. Since adding a third consul was impossible, the expansion called for a greater role for the praetor. Although praetors served as commanders in the provinces, one still remained in Rome. The Senate did not see the need to increase their number which remained at six.

As the number of provinces grew, the power of an annually-elected magistrate in a province could be extended for a second or third year. "The more praetors there were the greater the range of responsibilities, the greater the range of responsibilities, the increase in the opportunities for achievement and appreciation." (Holland, 5) The competition to become a consul was fierce. And it was obvious that most praetors would not become consul. With a successful provincial command, a praetor stood a better chance in his quest for a consulship.

In 123 BCE, the tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus initiated a new praetorian court to try cases of provincial extortion. Additional courts would be added between 123 and 91 BCE. By Cicero's (106-43 BCE) time there were a number of jury courts to handle various cases, among them murder and treason. Juries consisted of between thirty and sixty jurors, aediles, and were chosen by lot, voting in secret. A praetor would preside over the case. Civil cases were heard in two parts: in the first part, the case was heard before a praetor, who defined the issues. In the second part, the court decision, already decided by the praetor, was presented by a judge and jury.

The number of praetors changed dramatically over the following decades. The dictator Sulla (138-78 BCE) increased the number to eight, hoping to increase opportunities and foster competition. Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) increased the number to 16, not only to provide offices for his supporters but also to fill essential functions in the provinces. Augustus reduced the number to twelve and then to ten. Although changes were being made elsewhere, under the Principate, the praetor retained his position in Rome. Under the emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), the praetor continued to reside over the criminal courts while assuming new duties such as overseeing the public games. Later, some of the judicial duties of the praetor were undertaken by the consuls while the praetor supervised the treasury, but there was life after a consulship. While some individuals chose to became censors, others found a new life in a province. Former consuls and praetors were regularly given appointments as a governor of a province, thereby becoming proconsuls and propraetors. Most of the important provinces went to a proconsul while propraetors received the lesser ones. A propraetor outranked the legion's legate and was entitled to six fasces and six lictors (a proconsul got twelve).

The position of the praetor changed dramatically from the onset of the Roman Republic through the final years of the Roman Empire. His duties began with supervising Rome's judicial system, both civil and provincial, making life and death decisions, but as the size of the Republic (and later the Empire) increased, the number of praetors was increased from one in the beginning to ten under Augustus.