Vercingetorix (82-46 BCE) was a Gallic chieftain who rallied the tribes of Gaul (modern-day France) to repel the Roman invasion of Julius Caesar in 52 BCE. His name means "Victor of a Hundred Battles" and was not his birth name but a title and the only name he is known by. The Gauls kept their birth name a secret, known only to themselves and their close family, since they believed that knowledge of a person's true name gave others power over them. Vercingetorix is described as a tall and handsome charismatic leader, an inspiring public speaker, and demanding general. He is considered the first national hero of France for his defense of the land and was greatly admired in his time even by his enemies.

The Germanic Incursion & Caesar

Little is known of Vercingetorix prior to his rebellion of 52 BCE except that he was the son of an aristocratic Gallic chief and a respected member of his tribe. Vercingetorix's father, Celtillus, was an aristocrat and leader of one of the strongest tribes in Gaul, the Averni, who commanded the allegiance of some lesser tribes. The Averni maintained a long-standing feud with another Gallic tribe, the Aedui, who had their own allies to help maintain the balance of power. Although the tribes had united to attack and loot Rome in the 4th century BCE, they did not much concern themselves with matters outside their region.

The traditional lifestyle of the Gallic tribes was forced to change, however, when Germanic tribes began crossing the Rhine River into their territory. The Germanic Helvetii tribe found themselves uprooted by others on the move and crossed into the region of Gaul known as The Province (modern-day Provence, France). At this time, Julius Caesar was governor of nearby Hispania (modern Spain) but had moved into The Province and expanded his control there. When the Helvetii petitioned Caesar to allow them to enter the region he refused and then attacked. The Helvetii were easily defeated, but their incursion into the lands under Caesar's control caused him to consider the many other Germanic tribes and the possible problems they might raise in the future. He enlisted the aid of the Gauls as mercenaries to supplement his forces and drive the Germanic people back across the Rhine into their own lands. Vercingetorix was among these Gauls Caesar employed and led cavalry units for the Romans against the Germans in these battles. He gained valuable experience at this time in Roman warfare and tactics, which he would make use of later.

Vercingetorix Revolts

After the problem of the German incursion had been settled and they were driven from Gaul, Caesar expanded his control of the region and began instituting Roman law and culture. The Gauls refused to accept this new status as a conquered nation, especially because they had been so instrumental in driving out the Germans. A Gallic leader named Ambiorix of the Eburones tribe raised his people to revolt, claiming their right to freedom in their own country. Caesar took command of the Roman forces himself, instead of trusting the mission to one of his generals, and attacked the Gauls without hesitation or mercy. The Eburone tribe was massacred as an example to any others who might dare raise a force against Rome and, to underscore his message, any survivors were sold into slavery and the tribe's lands burned.

Vercingetorix could not stand for this and counseled for war on Rome to avenge the Eburones, but the others on the tribal council of elders were not willing to take the risk. Vercingetorix's father had died and he was now in the position of head of his tribe. He ignored the counsel of the elders and took it upon himself to drive the Romans from Gaul. He attacked Cenabum in 52 BCE and massacred the Roman settlement there to avenge the massacre of the Eburones. He then handed out the supplies of food the Romans had stored to his people and armed them with weapons the Romans had stockpiled. He sent messengers through Gaul to spread the word of his victory, inviting all to join his cause and save their homeland from conquest; almost all of the tribes responded.

Caesar was out of the country at this time and had left his second-in-command, Labienus, in charge. Labienus had never dealt with a guerilla war like the kind Vercingetorix now waged: making swift strikes on the Romans and their supply lines, then disappearing into the surrounding landscape. There could be no victory for the Romans because there was no enemy for them to engage. The Gauls struck and vanished like spirits and, besides this, it was now winter in Gaul and Labienus already had little enough food even before his supplies had been cut. If Caesar had depended upon Labienus to win Gaul for him the whole of the country's history would have been different. Caesar was not that kind of leader, however, and when he heard of the revolt and Labienus' troubles, he mobilized his army. Nothing would stop Caesar from reaching Gaul and destroying the rebel forces, and he marched his men through blizzards and over mountains, through snow up to six feet deep sometimes, to accomplish his goal.

The Scorched Earth & Avaricum

Hearing of Caesar's march on Gaul, Vercingetorix expanded the scope of his scorched earth policy; everything which could help the Romans in any way was destroyed. Whole cities, villages, even personal farms and homes were burned to keep them from falling into Caesar's hands and providing food or shelter for his army. The Gauls understood the necessity for this policy and the orders of Vercingetorix were obeyed until he came to the city of Avaricum. There the Gauls pleaded with him that it should be defended, not destroyed, as it was so beautiful and a point of pride for the people. Vercingetorix was against the plan and argued that Rome could easily destroy the city, slaughter the inhabitants, and turn whatever they plundered to their advantage. The Gauls persisted, however, and he grudgingly gave in to their request but refused to be trapped in the city with them. He rode off and camped less than twenty miles away; close enough to be of help, should they need it, but far enough to escape if the battle went to the Romans.

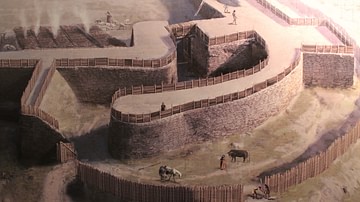

Caesar, at the head of his army, arrived at Avaricum to find it heavily defended and fortified. He immediately lay siege to it, surrounding it with trenches and towers, but the Gauls fought back fiercely. Caesar, in his memoirs of the time, writes:

The Gauls are truly ingenious at adapting ideas and putting them to their own use. They trapped our siege ladders with lassos, and then used winches to pull them within the walls. They caused our siege walls to collapse by undermining them. They are expert at this kind of work because of the numerous iron mines in their territory. And their entire wall was fortified with towers (7.22).

The defenders fought valiantly but were no match for Caesar's determined persistence. When they destroyed one siege engine, he had another built, and no matter how many siege ladders were roped and pulled over the walls, others took their place. Night and day Caesar's soldiers worked hauling earth and building an enormous slanting knoll against the outer wall of Avaricum. The siege went on, day after day, until a heavy storm blew in, and the defenders sought refuge from it indoors. Seeing the walls deserted, Caesar had his men roll one of the siege engines up the knoll and against the city's walls. The Romans then dropped the doors open and entered the city in the midst of the storm without resistance. No quarter was given to the people; of 40,000, only 800 escaped to tell of the massacre.

The stories of the fall of Avaricum rallied the country against Rome. Verceingetorix's army almost doubled in numbers in the following weeks. He continued his tactics of guerilla warfare, burning bridges, cutting supply lines, and carrying out effective strikes on Roman foragers. At the Siege of Gergovia, Vercingetorix managed to manipulate the situation so that the Gauls who had been enlisted by Caesar to guard his supply lines turned on them instead. Caesar was defeated in a direct assault led on the town and was forced to move on without taking it.

The chief advantage Vercingetorix had over Caesar in every encounter was his cavalry which could out-fight, out-run, and out-maneuver the Roman forces. Caesar recognized he needed horsemen who could equal the Gauls and so enlisted his former enemies, the Germans, who were well known for their skilled horsemanship.

The Siege of Alesia

Vercingetorix continued his surprise attacks on the Roman forces but was surprised himself when his cavalry was put to rout by the German mercenaries. He was driven from the field after one such skirmish and pursued. With no time to find a safe place in the countryside to hide, Vercingetorix led his men to the city of Alesia, which he then fortified as strongly as he could in the time he had.

Caesar arrived soon after him and, after surveying the city and the surrounding lands, he set up siege works, just as he had done at Avaricum, but also built defenses around his army to prevent attack from reinforcements which might try to relieve the defenders and lift the siege. Vercingetorix and his Gallic forces, as well as the citizens of the city, who had been taken surprise by his arrival, were trapped inside the city walls, and the food steadily began to run out. Vercingetorix first released all his horses and as many of his men as he could spare to go bring help; some of them were able to break through the Roman lines and escape. He then sent the citizens of Alesia out through the gates, hoping the Romans would let non-combatants pass as these were mostly the elderly, women, and children; the Romans lines held fast, however, and these people died slowly of starvation and the elements in the noman's land between the two adversaries.

Vercingetorix's cousin, Vercassivellaunus, had been sent out with his cavalry to bring reinforcements when Vercingetorix had first arrived at Alesia. He returned now with a sizeable force and struck Caesar's lines to the northwest at a small gap in the siege works. Seeing help arrive, Vercingetorix ordered his men out of the city to strike at the same place, and the two Gallic forces caught the Romans between them. The Roman line began to crumble, and victory seemed near for the Gauls. Caesar, watching from a tower, put on his well-known red cloak, instantly recognizable to his men and to the enemy, and entered the battle himself, encouraging his men as he struck down the enemy with his own sword. The Romans rallied and drove the Gauls back, winning the battle.

Vercingetorix's Death & Legacy

All hope was now lost behind the walls in Alesia. The hoped-for help had been defeated and driven off, and siege would continue. Vercingetorix understood there was no escape for himself and his men. At this point two different versions of events emerge: according to Caesar, the Gallic chiefs in Vercingetorix's army decided to hand him over to end the siege while, according to the historian Cassius Dio, Vercingetorix surrendered himself, taking Caesar and his staff by surprise in their camp. According to Cassius Dio, Vercingetorix "came unannounced, appearing suddenly at a tribunal where Caesar was seated in judgement" (40.41). Dressed in his finest armor, Vercingetorix was an imposing figure, even in defeat, and Dio claims that many in Caesar's camp were startled; though not, it seems, Caesar himself. Without saying a word, Vercingetorix slowly removed his armor and then fell to his knees at Caesar's feet. Dio writes, "many of those watching were filled with pity as they compared his present condition with his previous good fortune" (40.41). Caesar was not filled with pity, however, and had him taken away in chains and sent to prison in Rome. The defenders of Alesia were massacred, sold as slaves, or given as slaves to the soldiers for their service during the siege. When Caesar had completed the last details of his conquest of Gaul, Vercingetorix was dragged from his prison to appear in Caesar's triumphal parade through the Roman streets; then he was executed.

Although defeated, Vercingetorix's fame grew, and he became a popular cult figure and legend shortly after his death. The scholar Philip Matyszak notes that "the Gauls never forgot the time when they had united as a nation" and how "today he is widely recognized as the first national hero of France" (127). The courage and resolve of Vercingetorix as he risked his life and the lives of his people to resist foreign conquest and enslavement still inspires people in the modern day, and his name continues to be honored among the great heroes of the ancient world.